Within our portfolio’s cohort of SaaS CEOs, budgeting consistently ranks among the most challenging aspects of their jobs. This led to a recent post on this blog which argued in favor of now as a good time of year for SaaS businesses to examine previously un-budgeted expense items. That prior piece prompted a broader review of general budgeting processes, and provided a reminder of another simple but effective tip to help make budgeting less painful for SaaS CEOs.

First, let’s take a minute to recap why budgets are important for small-scale SaaS businesses, even those that are bootstrapped or that operate without a formalized board of directors. Most importantly, budgets serve as sense-makers for businesses. They quantify in specific terms whatever qualitative plans exist for the business. We generally codify initiatives and objectives in an annual Strategic Operating Plan, but these artifacts go by many names and can range widely in form. In whatever form your plan exists, a budget double-checks whether that plan is feasible and properly funded. It also helps enforce alignment of resources across the team and around that plan. Finally, budgets help businesses translate their inevitable idiosyncrasies into a set of universally understood measures (e.g., revenue, expenses, Rule of 40, etc.). In short: budgets = good. The problem is that budgets can be excruciatingly difficult to nail down, particularly for CEOs who may not have deep financial training (which, in the world of small-scale SaaS, is more the rule than the exception). For those typical CEOs, a persona-based approach to budgeting can help.

Wait…personas?! Aren’t those what our Marketing team uses to identify ideal customer profiles? Well…yes…but they can also help crystallize roles relating to the budget process. Specifically, no matter the composition of your team, someone will need to fill the following roles / personas in the budgeting process:

1. The Leader: This person is running point on the entire budgeting process, making sure that the right people are involved in the right ways at the right times. Although this has some tactical project management aspects to it, the CEO is best situated in small-scale SaaS organizations to serve in this role as the budgeting Leader. This is also the person who ultimately has last say on the numbers.

2. The Sensei: This person is a step removed from the budgeting activities and can provide a broader perspective about both the budget process and the actual work product. This person should offer a top-down view on what “Good” looks like — both in terms of the budget output itself, as well as how a given year’s budget supports the multi-year narrative of a company’s financial story. The Sensei is often a board member(s), but it doesn’t need to be. In particularly small SaaS businesses, this might reasonably be an outside advisor, accountant, or consultant.

3. The Model Master: This person is responsible for building, maintaining, and ensuring the accuracy of financial spreadsheet model that usually serves as the backbone of a budget. This person “owns” the (typically) Excel files and builds bottoms-up revenue and expense models. This often takes the form of a “three statement model” which adds a balance sheet and cash-flow statement to the omnipresent profit & loss statement. This Model Master is usually someone in a Finance role, but it can also be an outsourced expert who assists smaller businesses.

4. The Historian: This person has valuable institutional memory. The Historian provides context and empirical data from the past to inform future-looking forecasts. This is a lot more about subtle nuances in the business (e.g., sector seasonality, observed customer payment trends over time, sales cycle statistics) than it is about the headline numbers of a budget. This person is rarely the loudest voice at the table; but their voice is one that should be carefully considered.

5. The Water Carrier: This person is responsible for making material parts of the budget come to fruition. The Water Carrier is also the person / people who carry the quota that will turn the plan into reality (usually in the form of sales and (eventually) revenue). Unsurprisingly, the Water Carriers inject a dose of reality to budgets, particularly when The Leader and the Sensei get overly optimistic / ambitious. This person is usually the head(s) of Sales and Marketing, but can vary across different roles depending on the business model. Unlike other personas mentioned above, this person is almost never a consultant or part-time team-member.

We’ve observed that each one of these personas plays a critical role in successful budgeting processes. If even one of them is missing, it can throw-off the process and drive imbalances and gaps. Importantly, this does NOT mean that there needs to be exactly one person for each of these personas. In smaller companies one person may end up filling two or more of the roles outlined above. For instance, the CEO is often not only the Leader, but also the Historian. This tends to work just fine. The only thing to really avoid is violating the so-called Ghostbuster Rule (“…Don’t cross the streams!!”). Specifically, it’s quite problematic to have one role “moonlight” into someone else’s domain. The prototypical example is the CEO who decides that they want to suddenly dip into and out of the model when the mood strikes them. Don’t do that…it would be bad.

The Ghostbuster Rule

I’ll close with one last framework that can be quite valuable in the budgeting process: RACI chart (R = Responsible / A = Accountable / C = Consulted / I = Informed) can be great for clarifying which position in the org is responsible for what. Hopefully the example below is self-explanatory.

Sample RACI Chart for Budgeting Process

As valuable as the RACI is, though, we’ve observed that its utility is limited unless specific conditions are met. Rather, we find that it’s important to nail the personas above, before a RACI makes much sense to anyone.

In sum, personas aren’t just for Marketing anymore…they can definitely help make budgeting less challenging for all.

Budgets Again // aka: Personas — Not Just for Marketing Anymore was originally published in Made Not Found on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Like pre-Christmas sale commercials, blog posts about budgeting generally peak sometime in December — near the end of one fiscal year and before the beginning of the next. So why share a budgeting-related post toward the end of Q1? Because this is the time when many operators look at their budget and realize…something is off. I’m not talking about the top-line; hopefully bookings performance for most businesses is still tracking to plan. Rather, I am referring to expenses. What we’ve observed over time and across many companies is that some expense items commonly get overlooked in the (normally) Q4 budget planning process. And, like the green shoots of weeds in our yards, now is the season when those unwelcome cost items begin to first reveal themselves. But it’s still early enough in the year that those expenses can be identified, quantified, forecast, and proactively managed throughout the remainder of the fiscal calendar. This post calls out commonly missed expense items that might just warrant leaders’ attention and allocation within SaaS budgets:

1) Financial Audits: Not every private company invests in audited financial statements. But I’d argue that they should. And any business that has taken on institutional capital will undoubtedly be required to do so. These audits aren’t cheap (they generally run $20K — $40K), which is a big, unexpected pill to swallow for small-scale SaaS businesses. If a business has debt on its balance sheet, there will inevitably be additional audit activities (and more associated costs). Note: these and estimates throughout this post are for businesses in the $5M — $10M ARR range.

2) Performance Bonuses: This one shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone (it generally gets set at the outset of the prior year). Nevertheless, payment of bonuses often creates miscommunications and drives variances to budget. Perhaps it’s the timing complexity (“…remind me again, do year X bonuses get paid in year X, or in year X+1?!”). Whatever the case, now is a good time to think it through to avoid unpleasant surprises later.

3) User License / Vendor CPI Increases: This was less of an issue in prior years, but it’s a reality in the current high-interest rate / high inflationary environment. Particularly for companies that are expansive in their use of subscription-based solutions to power their enterprise, these increases can be substantial. As a rule, plan for 5% annual increases across the board…and then be pleasantly surprised when they’re less. Note: for volume-based contracts (e.g., Salesforce seats) it’s important to also update usage forecasts to ensure accuracy.

4) Legal Fees: They just…happen. Even in years that are relatively drama-free, legal fees just seem to have a way of finding us. And as the adage holds, “there are two types of lawyers: expensive ones…and REALLY expensive ones to fix the first group’s mistakes.” If possible, don’t skimp here. Make sure to set aside a healthy pool. Absent any other data, take a 3–5-year average of prior years’ fees…and gross it up per the CPI comment above.

5) Team Professional Development: Often the first line-item to get slashed in lean-times, this still has a way of adding up (e.g. a $500 / employee alloocation for a 30 person team = $15K). Please don’t kill this line-item entirely. If you want to lower the $ / Employee allocation…okay (but not great). But just be sure to keep this line-item realistic . SaaS leaders don’t expect team members to just stop investing in their learning in down-cycles…so, budgets shouldn’t pretend otherwise.

6) Tax Filings: Scrappy start-ups may be able to spend $0 to file their taxes, but it’s a dodgier proposition for growing SaaS businesses to do so. This one is close cousins to the point about financial audits above. And while it is generally much less expensive ($6K — 8K), it’s not $0.

7) Healthcare Increases: Ugh…don’t get me going on how the cost can continue to go up while the quality / coverage of the offering consistently declines. Whatever…just plan on a 5% — 8% increase annually.

8) Salary Increases: Okay, I’ll admit, this one rarely gets missed. Rather, business leaders generally have a great handle on it. But because most SaaS businesses’ biggest expenses are personnel-related, this one is super-material. And because retaining those people is so critical, it’s best for leaders not to hamstring themselves with an overly frugal assumption here. Although the “Great Resignation” thankfully seems to have abated, this is no place to low-ball.

There is a very long-tail of other line-items that could be included in this list. But hopefully the above capture the most material expenses that commonly get overlooked. And if this post helps SaaS operators avoid some unpleasant surprises as the year unfolds, then it will have been worth every penny readers paid for it. 😊

I’ll admit that I found it hard in the second half of 2022 to clear-off the white-space necessary to write many blog posts. Candidly, I’ve been in an extended slump on this front. When we find ourselves in a rut, it helps to have friends to lend a hand. With that in mind, I’m grateful to have many such friends in the early-stage SaaS community for just such situations. More specifically, I was delighted when James Marshall approached me with an idea for the “Made not Found” blog that leveraged his deep knowledge of analyst firms. The piece below is overwhelmingly the result of James’ experience and expertise, with a small bit of collaboration from me. Thank you, James, for generously sharing; and thanks to all for reading this post and helping the MnF blog get off the schneid early in ‘23.

Since my days of working for Gartner, I’ve learned to brace myself when mentioning B2B analyst firms to leaders of small-scale SaaS businesses. It’s not uncommon for one tech-leader to describe their industry analysts with admiration, and another to accuse theirs of downright corruption or extortion. A common sentiment is that paid research analyst engagements feel beyond our control, more akin to high stakes gambling than a rational, high-ROI growth strategy.

Over countless meetings with analysts, tech-CEOs, and investors, I’ve observed how great analyst-outcomes must be intentionally crafted by (and for) tech companies. Similarly, I’ve seen how analyst-related failures were quite predictable based on the actions taken (or not taken) by tech companies early-on in their engagements with analyst firms.

Let’s explore three common pitfalls to avoid, key questions to ask, and corrective actions to take. When thoughtfully navigated, these common stumbling blocks can become stepping stones, and serve as a strong foundation for meaningful analyst outcomes.

Pitfall #1: You invested money with analysts who don’t advise your target-market.

Too often, companies pay analyst-firms before confirming how those analysts plan to cover their space in the SaaS universe. This is a costly mistake that results in wasted dollars and time spent with analysts who don’t actively advise your target-buyers.

Key Question to Ask: Do these industry-analysts advise your target-buyers on how to buy solutions like yours? This is an especially critical point for vertical or niche SaaS businesses to confirm.

Key Action to Take: Analyst Interview — Just like you would interview someone for a position in your company, it’s important to take the time to properly interview any prospective key analyst. Discuss the below questions (and do so before any money changes hands!):

· How many conversations a month do you have with our target buyers?

· What is the most common business profile of these target-buyers you advise (revenue, employee count, industry, etc.)?

· What kinds of questions do our target-buyers ask you?

· What challenges are these buyers facing when choosing a solution?

· What kind of research do you plan to write this year? How will it help these buyers?

· Who are the biggest players in this space that my company competes with?

· Do you plan to rank vendors in this space? If so, what criteria will inform your decisions?

Questions like these are the beginnings of a high-leverage analyst engagement. From here, a well-executed engagement strategy will prove more attainable. Conversely, choosing an analyst based on brand awareness (or any other less informed criterion) commonly and predictably leads to dissatisfaction with one’s analyst.

Pitfall #2: You don’t have a strategy for turning analyst-investment into revenue growth.

While an unaimed arrow never misses, it’s best to approach analysts intentionally. This is especially true in the early days of working with an analyst.

Key Question to Ask: What steps can we take to convert the analyst’s influence into our firm’s revenue growth? This can also be a good question to directly and candidly ask the analyst (while acknowledging it is exclusively our job, not theirs, to drive our revenue growth). However, don’t be discouraged if they avoid specific talk of outputs (such as research mentions or referred business). Analysts closely guard their reputation of objectivity, so they generally won’t “go there” in terms of discussing tangible results…but achieving such outcomes remains possible.

Key Action to Take (#1): Identify Strategic Goals — Begin by internally outlining your 12-month goals for the relationship. There are three revenue-generating outcomes in analyst relations:

· Research Mentions: When your company is named in published research, your solutions get shortlisted more often. Your sales team can also leverage this research for instant credibility.

· Referred Business: During a direct conversation with your sales prospect, an analyst recommends that the prospect evaluate your company’s product.

· Insight that enhances your competitive position: This is the most overlooked benefit. As I’ll explain below, analyst-advice is directly correlated to the probability of being named in research or recommended for a shortlist.

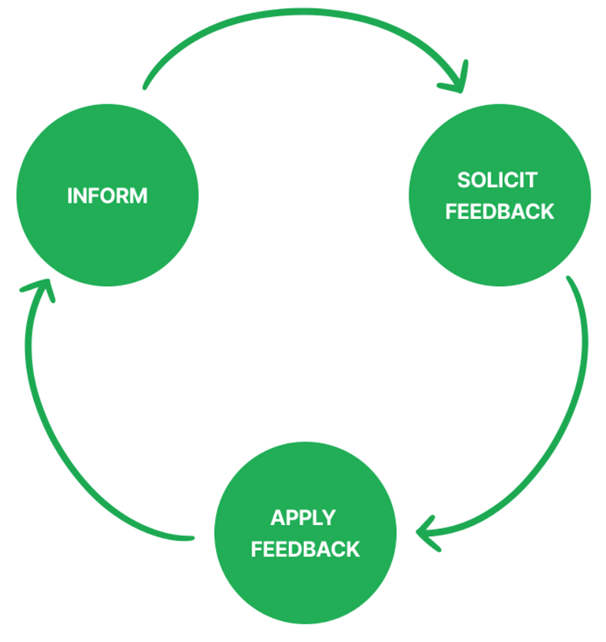

Key Action to Take (#2): Inform, Solicit Feedback, Apply — Here’s the secret: Nobody calls their own baby ugly; not even analysts. Leverage this human tendency by making analysts feel heard in some of your company’s critical decisions.

To illustrate this point, analyst-success can be distilled to the below cycle: inform the analyst about your product, solicit feedback, apply that feedback (if agreeable to your own vision), repeat.

Example: Ask the analyst to prioritize your feature-roadmap based on needs they see in the marketplace. This will be a valuable point-of-view that captures an influential analyst’s mindshare while helping to create an emotional investment in your company’s success. Their output could also save your company countless hours of internal debate!

Real-World Outcomes: The answer to your target-buyer’s question of “Who should we shortlist?” can be found among the vendors who ask that same analyst, “What features do you think are most important for our customers?” Analysts will shortlist vendors who align with their view of the marketplace. The same rule applies for tech companies hoping for favorable research coverage.

Pitfall #3: You’ve assigned the wrong people to speak with the analysts.

It’s common for tech leaders to invest significant capital with analysts, only to assign a lead-gen focused marketer to speak on behalf of their company. Those two parties can’t typically hold a meaningful conversation about your company’s strategy. Analysts catch on to this lack of investment in the relationship by leadership, and the impact to your brand is negative.

Key Question to Ask: Who in our company has the optimal blend of (1) seniority, (2) product / market vision, and (3) time to invest in relationship-building with the analyst?

Key Action to Take (#1): Put leaders in the meeting — The best people to speak with the analysts are the people with the blend of these three attributes; and those tend to be the CEO, the Head of Product, and the Head of Marketing (if they are responsible for packaging, pricing, and messaging…not just lead gen). Up until Salesforce surpassed $250m in annual revenue, Mark Benioff was well known at Gartner for his raucous debates with analysts. He even hired the analyst with whom he disagreed the most!

Key Action to Take (#2): Assign a separate show-runner — While tech leaders should be able to allocate the time to engaging substantively with analysts, they rarely have the bandwidth to establish, manage, and execute their company’s analyst strategy. Be disciplined about assigning someone to run the overall strategy of your analyst engagement, while surgically inserting the right leaders in the actual analyst meetings. This teamwork results in maximum impact. You can assign this strategy to someone internally or to an outside firm (just be careful to find one with real analyst experience, not a generic PR firm).

Conclusion: The Payoff — Intentional engagement with analysts creates significant momentum for businesses. That benefit is felt 10x for startups, where an analyst’s 3rd-party validation provides a level of credibility usually reserved for much larger companies.

For this reason, some tech-focused PE and VC firms spend millions of dollars each year with analyst firms. These investors mandate a well-executed Gartner and Forrester strategy as part of their value-creation playbook. Much the same, some SaaS founders and leaders are savvy analyst-relations pros who execute their own version of these strategies.

These leaders are in the minority and their analyst growth strategies are far from being a commodity. By taking the right steps to pair your company leaders with the right analysts, you can create an analyst-strategy that is a real accelerator to your company’s growth.

A recent post on this blog identified different types of client feedback groups that small-scale B2B SaaS businesses can set-up to intentionally solicit input about their market and solutions. That post went on to assert that managing such groups can be difficult and costly in terms of time, resources, and money. In retrospect, that was probably only partially helpful. This piece aims to improve and expand upon the last one by offering (a) a case for why programmatic client engagement is well worth the investment and (b) a few tips for avoiding some of the (many) mistakes that we’ve made on this front over the years.

It’s Expensive // Is it Worth It?

Yes, it really is. There are countless ways that such groups can benefit SaaS businesses; we’ve coalesced around 5 big ones that we hope to get out of such initiatives.

Avoiding the Pitfalls:

Hopefully the case is clear for why client engagement groups are well worth the effort. So, now for a few words to the wise in terms of do’s and don’ts for managing them:

Hopefully this follow-up post offers a valuable expansion upon its predecessor. In sum, investing in customer engagement is well worth the effort. But, as in all things, a bit of forethought and awareness of pitfalls should make that endeavor more rewarding with less risk.

One-size-fits-all seems to work fine for a few things. These arguably include: plastic rain ponchos, ping-pong paddles, the Flexfit ball caps that my dad likes to wear, and those awful grippy-socks handed out on trans-oceanic flights. For everything else, though, one-size-fits-all is brutal — always sub-optimal, often ineffective, and sometimes flat-out painful.

This principle holds true in many aspects of the small-scale SaaS world. And yet, we SaaS leaders consistently fall into the one-size-fits-all trap when it comes to customer engagement and setting up a formalized channel for soliciting actionable client feedback. There are many reasons for this including the fact that early-stage SaaS businesses often entirely lack an intentional approach to collecting market feedback; and launching an inaugural customer advisory board (often referred to by such acronyms as CAB, PAB, SAB, PUG, BUG, etc.) legitimately represents a major leap forward. Really, it does. Still, a one-size-fits-all approach to customer engagement can sometimes create as many problems as it solves. To describe and to combat that, this post draws on observations across many years & multiple companies to offer a framework for thoughtfully selecting an approach to customer engagement that best suits a business’ specific needs.

First, let’s introduce a few terms that will be useful to any discussion about programs for soliciting customer feedback:

· Focus groups / 1-on-1 Interviews: When conducting a focus group, researchers gather a group of clients / customers / users together to discuss a specific topic (or they do it on a 1-on-1 basis). Usually, the goal is to learn people’s opinions about a product or service, not to test how they use it. On this point, let’s draw a distinction here:

· Surveys: Standardized data collection from clients / users on a defined market or particular product.

· Tools / Data: Methods for gathering broader insights, including product usage stats, industry data, heat maps, A/B testing, etc.

· Client Groups: Convening knowledgeable clients who provide insight on the market and feedback about your solutions via the methods described above.

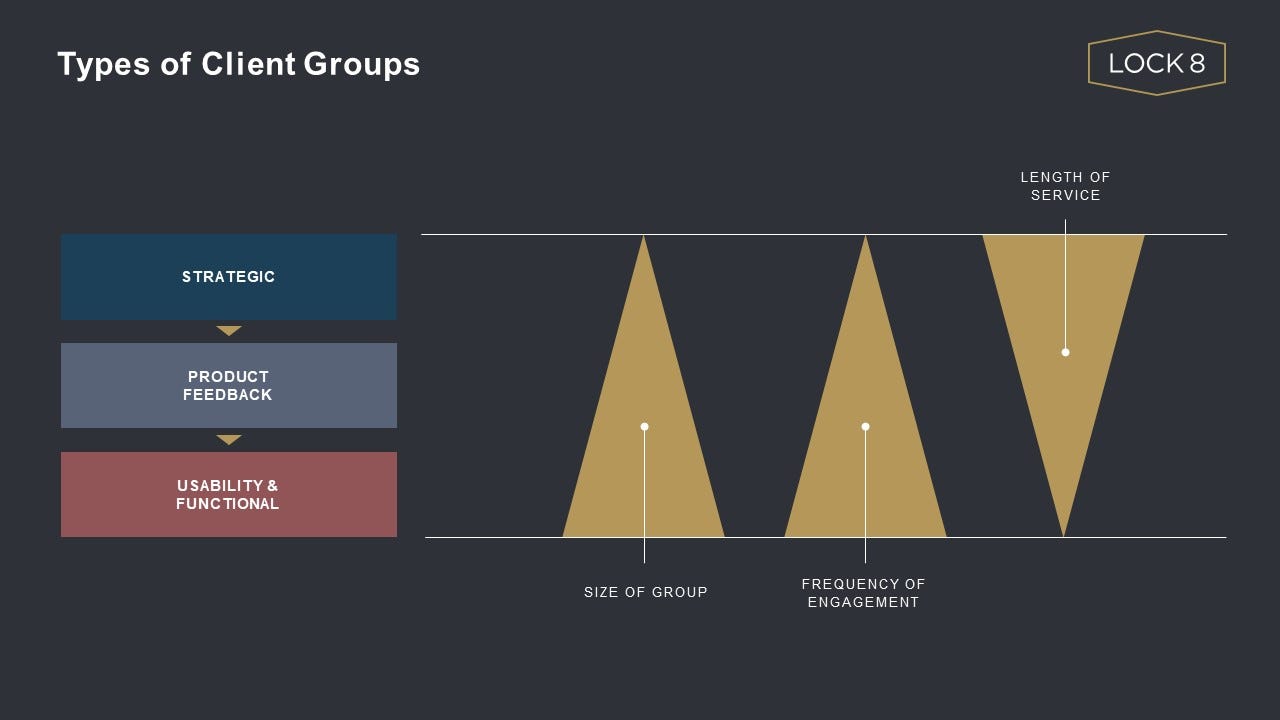

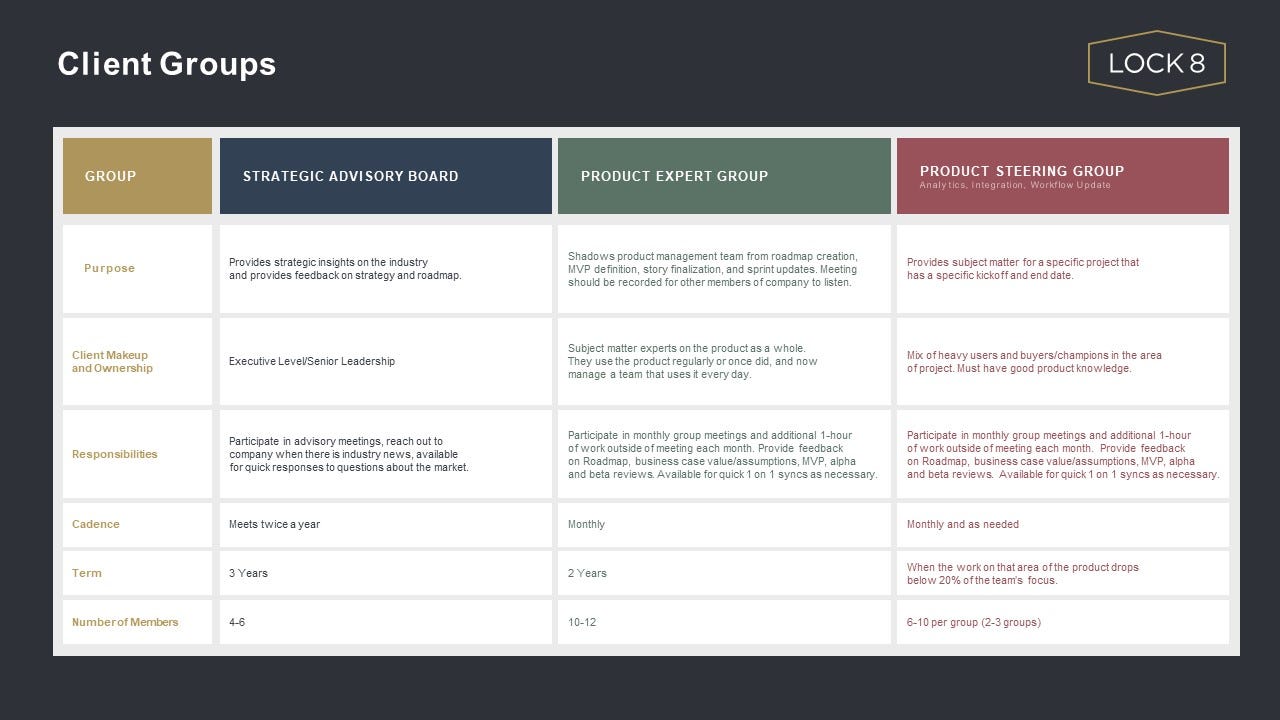

To be clear, all of these can be valuable, but this post focuses on the last of these forms of engagement — client groups. While there are arguably countless different flavors of client groups, we’ve observed three general types, as follows:

Hopefully these brief descriptions make a clear case for how each of these groups would serve vastly different purposes on behalf of a business. The graphic below double-clicks further into how these groups typically differ in terms of size, meeting frequency, and longevity of commitment.

To summarize:

The table below adds some quantifiable detail around how we tend to think about and structure programs for each of these types of groups.

To go one step further, and for those so inclined, it is also worth expanding upon this table as your programs become more formalized. We tend to add the following rows to nail-down additional criteria, including:

In closing, a few words about why these distinctions actually matter: Most importantly, small-scale SaaS businesses have a finite set of resources; and engaging with these groups is hard(!). We think about the challenges of managing user groups in two categories, as follows:

I. Time & Resources — it takes a lot of both; below is a set of related tasks:

II. Mixed Results — the hard reality is that these forums don’t always yield the expected outputs; below is just a small sampling of ways these groups can run off the rails:

As a SaaS business evolves its programs for engaging with customers, it would be ideal to simultaneously manage a portfolio with one (or more) of each of these user groups. Sadly, (to repeat) small-scale SaaS businesses constantly balance the tension between an infinite set of possibilities against tightly constrained resources. Given that, it’s important that they ruthlessly prioritize in all areas, including how to programmatically solicit strategic / product feedback from their clients. So…with many small-scale SaaS businesses looking first to mature to the point of having even just ONE of the customer feedback groups described above, it’s important to do so with intentionality. Because, as with most things, one size does NOT fit all…avoid the plastic poncho; and choose wisely.

A word of thanks to Paul Miller, ardent product management leader, now CEO, and previous thought partner to this blog, who recently helped me to crystallize “what good looks like” in terms of customer engagement programs.

3

I recently wrote that business dashboards are instruments of control. That observation and the related post, while hopefully helpful, made some general assumptions in discussing dashboards. So, this post takes a crack at addressing an ongoing open point about the existential nature of dashboards: what exactly is their purpose?

Although Stephen Few provides an excellent definition, it leaves room to debate dashboards’ ultimate objective.

Definition: A dashboard is a visual display of the most important information needed to achieve one or more objectives; consolidated and arranged on a single screen so the information can be monitored at a glance. — Stephen Few

Our observation is that the primary purpose of most dashboard initiatives lies somewhere between two general approaches, which can be loosely described as Reporting on one end of a spectrum, and Analytics on the other. The problem many operators face is that their efforts can wind-up betwixt and between the two, often without even realizing it. These two poles offer useful guardrails when considering the objective of any dashboard initiative; and examining and choosing between them helps to clarify many aspects of that dashboard. This kind of clarity, in turn, can help align and ultimately exceed stakeholder expectations.

Five seemingly simple (but deceptively challenging) questions offer a good start toward getting people on the same page:

Although they’re a good start, these questions can admittedly be a bit opaque for practical application. To make them more actionable, we expanded the questions into a “quasi-diagnostic” table. This table captures attributes and examples of each approach, to help leaders identify and intentionally choose how best to prioritize and proceed.

Identifying these characteristics and having open conversations about each can certainly de-mystify the purpose of dashboards and put an organization in a better position to optimize its time and resources.

A few caveats / qualifiers / comments about the above:

In closing, it seems worth following-up with one of my favorite go-to questions: So what? Why does the debate about dashboards’ purpose even matter?! Quite simply, intentionality matters when it comes to metrics measurement. Contrary to popular lore, it’s not so much that “what gets measured gets managed;” Danny Buerkli does a great job debunking that familiar trope here. Rather, as Buerkli succinctly argues, “Not everything that matters can be measured. Not everything that we can measure matters.” So true. And because sub-scale SaaS businesses operate in a world of big dreams but small teams, focus is our friend. Like any other product or service, dashboards should have a clear approach, objective, and target stakeholder…lest they lose their incisiveness and value. So, when considering dashboards, as with all things related to business building — choose wisely and with intent.

I’ll admit that I love a good dashboard. As an aid to SaaS operators seeking to optimize business performance, dashboards can be invaluable.[1] Stephen Few defined a dashboard as, “a visual display of the most important information needed to achieve one or more objectives; consolidated and arranged on a single screen so the information can be monitored at a glance.” This is a useful definition that makes clear: dashboards are instruments of control. Specifically, just as dashboards within vehicles aid in the controlled navigation of those machines, company dashboards help leaders drive organizations forward while controlling speed, direction, and business health. And yet…the irony of dashboards is that before advancing any aspects of a business, sacrifices must first be made in the very same areas that leaders seek to optimize. To go fast, you must first go slow. To go far, start with steps backward. To increase control, make a conscious decision to loosen oversight.

With these contradictions in mind, this post strives to flash a warning light (see what I did there?) by dispelling any illusions leaders may have about scoring easy wins with dashboards. Rather, it introduces some questions to ponder and detours to explore when considering dashboard initiatives. Hopefully these will help folks achieve the goal of getting past the entry-ramps and using dashboards to confidently drive the business forward in the fast lane.

Control: This is What Democracy Looks Like? Advocates of dashboards sometimes tout them as nobly delivering democratization of data. But do dashboards inherently reinforce the notion of one person, one vote? Not necessarily (the term “executive dashboard” seems to succinctly refute this point). Rather, a key question to be answered early in a dashboarding effort centers around data roles, rights, and privileges. Who gets access to what data? Is the dashboard’s audience the CEO? The Leadership Team? Every team member within a business (including / excluding contractors and consultants)? Should there be a curated / filtered set of data for each? Oh, and, what about the board of directors?

A related question centers on how dashboard information is consumed — on a push or pull basis? Purists might argue that dashboard users should be able to “pull” information. That is, they should be able to access what they want, when they want it, and manipulate the information to suit their needs. The problem, of course, is that this is horribly inefficient and variable — we humans rarely know what we want until someone presents it to us as a solution to our needs. That view supports the position of what I call “curators” who believe dashboards are best served up on a push basis. In an extreme version of this model, some analyst-type packages up KPI’s into a report and shares it with a defined set of stakeholders on an agreed-upon cadence. This approach is certainly efficient / prescriptive, but not at all a beacon of data democracy.

My own experience here is that the middle is marvelous. Dashboard information is most valuable when shared broadly with a large number of stakeholders and with minimal access constraints. But the dashboard should also be structured and streamlined, not just a filtered database that can be used to spin-up infinite ad-hoc reports (after all: if everything is important, then nothing is). Finally, regularly scheduled all-hands reviews of the dashboard by company leaders are key to offering commentary and context. This helps provide all stakeholders with a clear understanding of “what matters, how we’re doing in those areas, and what each of us can do about it.” In this way, leaders can absolutely gain more control over their business through dashboards. But they must first be prepared to loosen the reigns on potentially sensitive data and to make themselves vulnerable by sharing it (in good times and bad). I’d argue this approach doesn’t represent a pure (data) democracy, but perhaps it is more like a high-functioning (information) republic.

Speed: Slow is Smooth, and Smooth is Fast: This useful adage from the Navy SEALs has been widely analyzed (e.g. here, here, and here). The general gist is that “the best way to move fast in a professional setting is to take your time, slow down, and do the job right.” This is particularly prescient in connection to implementing business dashboards. As leaders, we want dashboards to serve as an accelerant: to provide early alerts about deviations versus plan, to streamline our decision-making, and to speed the pace of collective results. But…to go fast, we need to start slow. A big-bang approach simply doesn’t work when creating dashboards. Never have I seen a version 1.0 dashboard that was worth a darn. In fact, “if you move too quickly, you bump and bounce and veer from that path because you are frantic, trying to do too many things at once.” Rather, a deliberate and iterative approach to creating dashboards allows leaders to test, learn, adapt, and develop a dashboard that truly serves the needs of the business — over time.

A corollary to leaders’ “need for speed,” is the desire to automate the updating of dashboards. Like a scene from Minority Report, the dashboards in our imaginations should miraculously and effortlessly pipe future-illuminating intelligence directly to our brains on a continuous loop. It’s a compelling vision; and automated updates to dashboards are totally doable — eventually. But a fair degree of manual work is necessary to get a dashboard stood-up. Manual data-entry (the antithesis of tech-enabled efficiency) is often required at the outset of a project, particularly in the early iterations described above. Even after graduating from data-entry, labor is needed to enable efficient and error-free data feeds from different company systems. It. Just. Takes. Time.

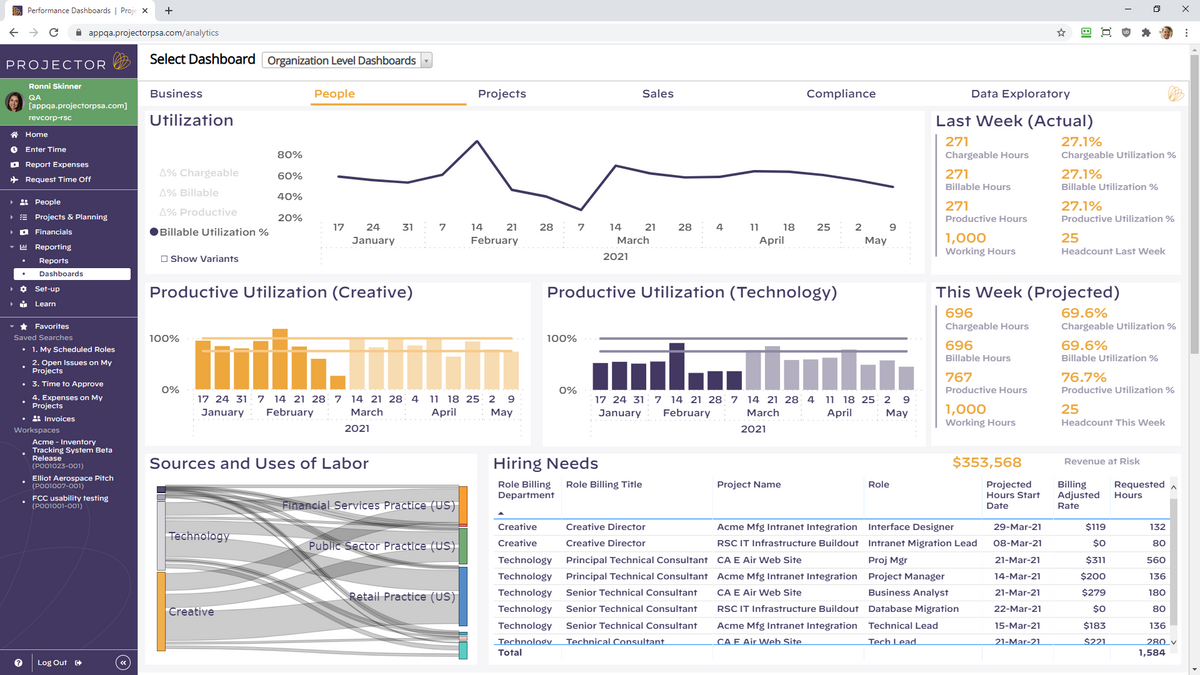

In my view, balance is helpful in navigating the tension between slow and fast. Having botched overly ambitious dashboard initiatives, I’ve learned to start small and slow. It’s wise to avoid throwing out an otherwise valuable metric, simply because it is hard to collect — report what matters to the business, even if it requires manual data entry. Conversely, don’t prioritize the automation of data collection early in a dashboarding effort. Doing so can mean “letting the great be the enemy of the good;” and technical glitches have killed countless promising projects. One of my all-time favorite dashboards (a snippet of which is included below) took 18 months to get right. Initial versions were brutally tedious to update — manually. And even in its prime, it was never visually impressive. But, by taking our time, we eventually created an astonishingly valuable tool that helped accelerate the business.

Horizon: Is Real-Time Really the Best-Time? Another common hope among leaders is for dashboards to help predict the future. This translates into wanting to (a) report the most up-to-date information and (b) measure that information in shorter and shorter chunks of time — by month, week, day, hour, and even by the minute. This works well for many metrics, where recency really matters. For SaaS businesses, such metrics might include website visitors, numbers of qualified leads, product usage metrics, or volumes of support tickets.

But other metrics evolve on a slower cadence; and measuring them over short time horizons is less helpful. As a correlate, I’m reminded of the recommended method for taking one’s pulse: top medical organizations advise counting someone’s pulse over a 60 second span. Although it would be a lot more efficient to measure someone’s pulse for only 2 seconds and then multiply the result by 30…that would give a far less accurate reading. Similarly, many metrics in SaaS businesses require measurement over a longer period, lest the results be useless or misleading. This is particularly true in enterprise businesses selling large dollar subscriptions over long sales cycles. In such cases, one week’s worth of data can have very limited utility; rather, we need to see data over a quarter or even multiple quarters. Examples of these longer-lead metrics include: sales and marketing conversion rates, contracted new bookings performance, measuring execution against hiring plans, or quantifying employee engagement. All of these tend to take a long time to materialize and are inherently “lumpy” in nature.

Where this can lead to dashboard-related trouble is when we try to measure all metrics on a uniform cadence over consistent time horizons. Rather, leaders need to approach dashboard projects with realistic views on just how real-time their measurements should be…and apply time horizons unevenly across different metrics.

To further complicate this issue, today’s results are often best interpreted by looking backward in time. This is challenging for many reasons. First, we often don’t have access to good historical data, which is commonly the motivating factor behind the dashboard project in the first place. Looking backward in this way also contradicts every instinct of the future-focused leader who has undertaken a dashboard project for the stated purpose of more proactively looking ahead. While real-time data is certainly appealing, successful dashboard efforts must also consider both current and past data over long time-horizons.

Conclusion: In sum, dashboards can yield valuable results for businesses and offer great benefits to thoughtful business leaders. Specifically, they can increase the control, speed, and foresight with which the business operates. But none of these benefits comes without a cost. And that price is often paid in the form of leaders first making sacrifices, or investing time and resources, in the very same aspects of the business that they wish to ultimately optimize.

Footnote:

[1] Dashboards are also imperfect and highly variable, as argued well here and here.

In September of 2020, I attended SaaStr Annual and wrote about it here. It was my first fully virtual multi-day conference; and there was a real novelty factor to it. Seven months and several digital conferences later, I’ll admit to eagerly awaiting the return of in-person industry events. Still, I was pretty fired-up to take part in SaaStr Build this week; and it did not disappoint. The return on my time-invested was high, with a mix of valuable takeaways and follow-up research to do. My hope in this post is to succinctly share some of my personal highlights with anyone interested but unable to attend the event. Specifically, below are 5 content takeaways and 5 general observations, hopefully in under 5 minutes of reading. Ready…go.

CONTENT:

GENERAL REFLECTIONS:

Parting Thought: To make up for having cheated above, I’ll add one last point. I commented in September on the general air of uncertainty at that time and the silver lining at SaaStr Annual of a related (and welcome) vibe of community / humility among attendees. With SaaS multiples at all-time highs, that uncertainty seems to have been replaced with open bullishness at SaaStr Build; and the event certainly offered ample grounds for optimism in the space. My hope for the SaaS community in the coming quarter+ is that we continue to experience sustained market strength…AND / BUT that the same sense of community also endures. Here’s to 2021.

Tis the season…not for jolliness…but for annual forecasting. Countless companies spend the month of December frantically closing out the current year, while scrambling to codify goals for the fiscal year ahead. So, for many small-scale SaaS businesses, this is decidedly NOT the most wonderful time of the year. Rather, when it comes to financial planning and analysis, it can be a time of feast or famine. Famine in this case is represented by simply not doing any intentional planning. A surprising number of small software companies don’t share fiscal goals with their teams, or even set formalized financial plans whatsoever. Feasting, in this case, occurs when a leader’s eyes are bigger than their mouth, resulting in an unreasonably aggressive growth plan based on exuberant hope more than rational thought. Perhaps this is less like feasting, and more like binge-eating junk-food (in that it is based on impulse, offers a temporary jolt, induces sickness soon after, and is terrible health-wise in the long-term). But neither of these extremes is necessary; and a thoughtful plan does not require gobs of bureaucratic process (one of the primary excuses offered for this feast / famine dynamic). Rather, we’ve seen that the simple concept of triangulation can efficiently produce the building blocks of an informed financial plan that balances multiple perspectives on the business. Here’s how it works:

First thing first, this approach focuses overwhelmingly on setting the top-line goals for a business. The long-pole in the financial planning tent is this top-line goal (also known variously as: revenue, bookings, ARR, and sales). This is because sales performance ultimately dictates the money flowing into the business and highly influences the expense levels the business can sustain. Note: admittedly this is more nuanced in businesses with outside funding, but eventually holds true as they mature toward cash-flow breakeven. Bookings are also the most highly variable / least-controllable aspect of any plan, as discussed in this prior post; and getting the top-line goal wrong can unleash a cascade of pain throughout the entire business. For these reasons, setting an appropriate top-line goal is the critical step in developing a sound plan. The reality is, that this goal must be ambitious enough to please financial stakeholders, realistic enough for the team to execute with confidence, and based credibly on relevant historical data (while also not being shackled to the past). A tall order, indeed.

To ultimately arrive at an appropriate goal, we like to start by pulling together three different top-line targets based on three distinct views into the business. Later we’ll compare / contrast / compromise across the three resulting targets, hence the term triangulation. The three perspectives in play are (1) top-down, (2) left-to-right, and (3) bottoms-up, as follows:

Generally speaking, Left-to-Right tends to be the middle-child in our family of goals — neither the aggressive hyper-achiever, nor the black-sheep slacker — just…meh. (Note: this last statement comes from a card-carrying middle-child).

Bottoms-Up: This approach constructs a bookings goal from the bottom up and represents the perspective of the person / people responsible for driving day-to-day sales results (e.g. CRO, VP of Sales, VP of Marketing). This perspective starts from $0 on day 1 of a fiscal year and assumes “nothing happens until someone sells something.” More mechanically, it establishes a bookings forecast from its component parts by building up a notional population of representative sales deals across a time-period. This approach tends to incorporate multiple inputs into detailed models, including:

The resulting forecast from such an approach tends to be quite conservative, sometimes prompting accusations of sandbagging by its advocates. Almost without fail, this will be the lowest among our trio of prospective top-line targets.

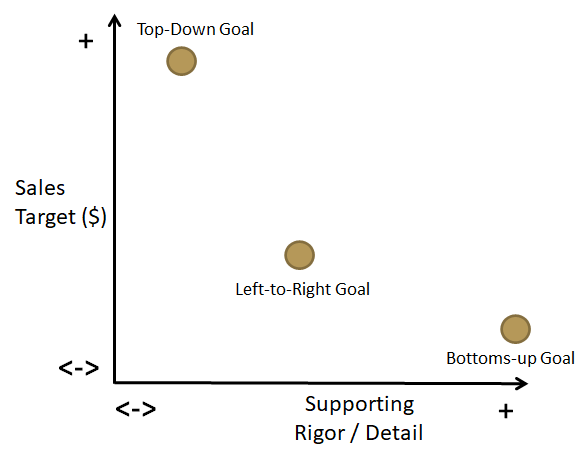

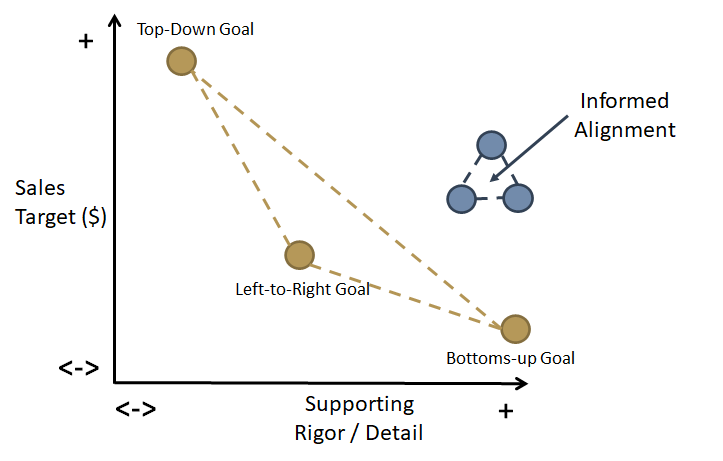

Triangulating: Simply quantifying each of these different perspectives is certainly a step toward a more inclusive and informed top-line goal. But a bit more work at this point is what yields the real progress. The truth is that the three different methodologies produce widely divergent results, both in terms of target figures and the rigor used to arrive at them, so compromise is necessary. Graphically, these could be plotted like this.

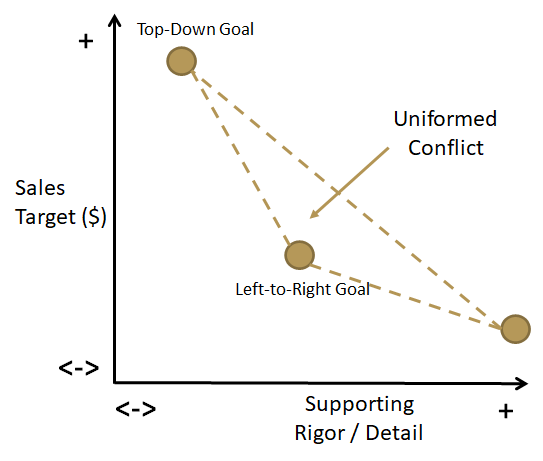

Each goal has its own shortcomings, and none of these goals tends to unilaterally offer an ideal bookings target. Without further discussion, these different data points simply shine a light on the misalignment that commonly exists across the various stakeholders. This can look like this:

But these inputs also provide the forum for an interactive discussion around the drivers of each. Optimally, organizations can move beyond this zone of Uninformed Conflict simply by asking pointed questions of each goal:

This exercise forces people out of their default perspectives and drives productive (albeit, often uncomfortable) discussions. Inevitably, this drives more informed goal-setting and better alignment across the business…and quite frequently, it helps move the top-line goal up and to the right in our now-familiar graph:

Conclusion: The top-line goal is critical to annual planning efforts. To be fit for purpose, it must balance ambition, credibility, and executability. Only by clearing this bar will it fully serve its multifaceted purpose: to please optimistic financial stakeholders, satisfy the inherent skepticism of internal number-crunchers, and pass the “red-face test” among the troops. Admittedly, this is only a start; and many other components are needed to really nail annual planning. But getting this goal right is a great foundation around which to build; and triangulating across these multiple perspectives is a simple way to inform this process. Plus, doing so is a good way to make the New Year something really worthy of celebration by all stakeholders.

From time to time, we use this forum to share observations and trends from webinars or virtual conferences (here); and sometimes we invite guest-bloggers to offer insights from their own experiences (here and here). This post does both of those things at once. Our friend and peer, Mike Dzik, is a Growth Partner at Radian Capital (full disclosure: one of Lock 8’s investors), where he works with Radian’s portfolio companies on their respective go to market strategies spanning marketing, sales and customer success initiatives. Last week, Mike attended the TOPO Virtual Summit a three-day virtual conference for sales, sales development, and marketing practitioners; and he was generous to share with us his impressions of the event. He’s also agreed to allow us to share those observations here on Made not Found. So, with no further ado, I’ll turn it over to Mike, below:

I hope everyone is doing well and off to a fast start for Q4. I spent some time attending the TOPO Virtual Go To Market Summit this week and wanted to share 5 key themes surrounding 2021 (below).

Thanks, Mike, for these pearls. There are so many good virtual events out there; and it is impossible to free up the space to attend them all. We’re grateful to benefit from your participation in, and distillation of, the thought leadership coming out of the TOPO Virtual Summit.

-Todd