Like pre-Christmas sale commercials, blog posts about budgeting generally peak sometime in December — near the end of one fiscal year and before the beginning of the next. So why share a budgeting-related post toward the end of Q1? Because this is the time when many operators look at their budget and realize…something is off. I’m not talking about the top-line; hopefully bookings performance for most businesses is still tracking to plan. Rather, I am referring to expenses. What we’ve observed over time and across many companies is that some expense items commonly get overlooked in the (normally) Q4 budget planning process. And, like the green shoots of weeds in our yards, now is the season when those unwelcome cost items begin to first reveal themselves. But it’s still early enough in the year that those expenses can be identified, quantified, forecast, and proactively managed throughout the remainder of the fiscal calendar. This post calls out commonly missed expense items that might just warrant leaders’ attention and allocation within SaaS budgets:

1) Financial Audits: Not every private company invests in audited financial statements. But I’d argue that they should. And any business that has taken on institutional capital will undoubtedly be required to do so. These audits aren’t cheap (they generally run $20K — $40K), which is a big, unexpected pill to swallow for small-scale SaaS businesses. If a business has debt on its balance sheet, there will inevitably be additional audit activities (and more associated costs). Note: these and estimates throughout this post are for businesses in the $5M — $10M ARR range.

2) Performance Bonuses: This one shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone (it generally gets set at the outset of the prior year). Nevertheless, payment of bonuses often creates miscommunications and drives variances to budget. Perhaps it’s the timing complexity (“…remind me again, do year X bonuses get paid in year X, or in year X+1?!”). Whatever the case, now is a good time to think it through to avoid unpleasant surprises later.

3) User License / Vendor CPI Increases: This was less of an issue in prior years, but it’s a reality in the current high-interest rate / high inflationary environment. Particularly for companies that are expansive in their use of subscription-based solutions to power their enterprise, these increases can be substantial. As a rule, plan for 5% annual increases across the board…and then be pleasantly surprised when they’re less. Note: for volume-based contracts (e.g., Salesforce seats) it’s important to also update usage forecasts to ensure accuracy.

4) Legal Fees: They just…happen. Even in years that are relatively drama-free, legal fees just seem to have a way of finding us. And as the adage holds, “there are two types of lawyers: expensive ones…and REALLY expensive ones to fix the first group’s mistakes.” If possible, don’t skimp here. Make sure to set aside a healthy pool. Absent any other data, take a 3–5-year average of prior years’ fees…and gross it up per the CPI comment above.

5) Team Professional Development: Often the first line-item to get slashed in lean-times, this still has a way of adding up (e.g. a $500 / employee alloocation for a 30 person team = $15K). Please don’t kill this line-item entirely. If you want to lower the $ / Employee allocation…okay (but not great). But just be sure to keep this line-item realistic . SaaS leaders don’t expect team members to just stop investing in their learning in down-cycles…so, budgets shouldn’t pretend otherwise.

6) Tax Filings: Scrappy start-ups may be able to spend $0 to file their taxes, but it’s a dodgier proposition for growing SaaS businesses to do so. This one is close cousins to the point about financial audits above. And while it is generally much less expensive ($6K — 8K), it’s not $0.

7) Healthcare Increases: Ugh…don’t get me going on how the cost can continue to go up while the quality / coverage of the offering consistently declines. Whatever…just plan on a 5% — 8% increase annually.

8) Salary Increases: Okay, I’ll admit, this one rarely gets missed. Rather, business leaders generally have a great handle on it. But because most SaaS businesses’ biggest expenses are personnel-related, this one is super-material. And because retaining those people is so critical, it’s best for leaders not to hamstring themselves with an overly frugal assumption here. Although the “Great Resignation” thankfully seems to have abated, this is no place to low-ball.

There is a very long-tail of other line-items that could be included in this list. But hopefully the above capture the most material expenses that commonly get overlooked. And if this post helps SaaS operators avoid some unpleasant surprises as the year unfolds, then it will have been worth every penny readers paid for it. 😊

A colleague recently shared with me Benedict Evans’ tech trends for 2023 presentation. It’s amazing — 104 slides of compelling data that make sense of a dizzying range of topics, from interest rates to consumer behavior to global power-shifts to a new breed of digital gatekeepers. Before proceeding, I have two admissions to make: (1) I was previously somehow unfamiliar with Evans’ work; but I will pay closer attention going forward. (2) Although macro tech-trends conceptually interest me, I sometimes find it difficult to connect them back to our seemingly more pedestrian work of building small-scale B2B SaaS businesses. With these confessions in mind, this blog post is for practitioners like me. It cherry-picks just a few of the presentation’s many awesome slides and highlights points that struck me as particularly relevant to SaaS operators. It does not attempt or purport to summarize the presentation; and it’s certainly not comprehensive. Rather, it’s just a quick-share of my top takeaways — a codification of those points that I plan to revisit and bear in mind in the day-to-day fray throughout 2023. And they are…

Is it now time for the little players to have their day from an employment perspective? It was difficult during the pandemic for small-scale SaaS businesses to hire / retain top talent. To use a basketball term, the “possession arrow” in the resource economy seems to have shifted from employees back to employers. More specifically, with a quarter million veterans of big tech firms newly unemployed, what kind of a recruiting opportunity does this present for us? What roles could these people fill in our businesses, how best to recruit / on-board them, what support might they need to make the transition to small companies and to thrive in a less structured environment? This feels like a great, but fleeting, opportunity, let’s make the most of it.

2. Glass half empty, glass half-full (Slide 16):

This slide reminded me of an oft-cited pearl from the best software investor I know, “when it’s going well, things are never as good as they seem; and it’s never as bad as it seems when they’re not.” As a SaaS investor-operator, I found this slide encouraging. Particularly the last bullet: every market, every value-chain, every workflow, every customer engagement, every dataset is being rethought and remade — and there is still a ton of work to do on this front. When it can sometimes feel like every industry has already gone through digital transformation, this is an important point to remember. The following slide (about enterprise workloads in the public cloud) struck me as using different data to reinforce this same point.

3. Fragmentation (Slide 49):

This slide specifically addresses the steadily declining share of Nielsen ratings among the top-rated US TV shows over numerous decades. So, what does this have to do with small-scale B2B SaaS? What it highlights for me is that today’s most successful, top-performing shows only draw 10% of the available viewership. And they’re still winners. Perhaps not to the same degree as I Love Lucy back in 1955, but still massively successful. There are many niches, within which B2B SaaS businesses can thrive. And while they may need to garner more than 10% market share if they operate within a particularly small vertical, they don’t need to be all things to all people in order to prosper. If “focus is the friend” of SaaS operators, this is good news.

4. The ‘innovators’ dilemma costs real money… (Slide 55)

It’s hard to argue against being fist to market. But being the challenger does have advantages, and a lack of legacy baggage is one of them. This slide hammered home for me what small-scale SaaS operators inherently feel: it’s often more efficient / liberating / plain-old-fun to go-to-market as an innovative fast-follower than as the incumbent with tons to lose. Small-scale SaaS business should embrace that mentality and its many benefits.

5. Advertising is the price you pay… (Slide 69)

I’d never heard this fascinating 2009 quote from Jeff Bezos. And, although Evans goes on to illustrate that Amazon has since become the world’s largest advertiser, it’s a great reminder to budget-conscious SaaS operators.

In short, it puts a premium on ALWAYS focusing on ensuring that a business’ products are differentiated from those of competitors. Moreover, this highlights what is true in many vertical SaaS markets — that there are other, more effective means of communicating one’s go-to-market message (e.g. thought leadership content, earned media, word of mouth, customer references, community marketing, conferences, etc.). Said another way, should direct their energy into scalable and high-return organic marketing initiatives, rather than costly PPC efforts (aka advertising). Focus there.

6. The end of the American internet (Slide 95)

The “focus is your friend” axiom has a downside; and that is that it can foster short-sightedness. I found this slide to be a good reminder that even small-scale businesses should always be scanning the horizon to grow TAM and identify new opportunities to win customers. Wow, this slide is a mindblower — although the US may continue for some time to be the largest single market for B2B SaaS, other markets demand serious consideration.

I have no big finish to this post. Rather just a big thank you to Ben Evans for his fantastic work. It really is helpful, not just to the large players on which much of his work focuses…but also to small-scale operators who can learn from the trends he highlights.

As I’ve written previously, I’m not a fan of the term “playbook,” despite it being a metaphor that is used with reverence in many private equity circles. In my view, the reality facing small-scale SaaS businesses is too complex for 1-size-fits-all playbooks to be universally valuable. But I have also observed that a set of core disciplines consistently catalyzes the sustainable growth of capital-efficient SaaS businesses; and we regularly leverage several frameworks to reinforce these concepts. I was recently made aware that my enthusiasm for such frameworks or mental models had turned me into the proverbial “hammer,” to which everything looks like a “nail.” At the time, I was in a discussion with one of our portfolio company CEOs about a particularly thorny issue they were facing. As I unhelpfully tried to solve the issue with 2x2 matrices, “pattern recognition” drawn from other businesses, and a wealth of publicly available SaaS benchmarks, the business leader kindly said to me, “Hey…you know…not everything is a F8*%^&! framework.” Boom — direct hit.

This simple reminder got me thinking about situations in which a framework or mental model (or a playbook(!)) really are NOT helpful to operators of SaaS businesses. I’ve shared a few of these below. My hope in doing so is that it helps leaders of small-scale SaaS businesses to distinguish between the many situations when a pre-established framework / approach can be extremely helpful…versus those critical instances when a totally unscripted response is not only warranted…it is needed.

Hard Things: In his epic work The Hard Thing about Hard Things, Ben Horowitz argues that building a software business reveals countless problems for which there just aren’t any easy answers for leaders. Those include firing friends, poaching competitors, and knowing when to call it quits (among many others). These are very real, very important, very “anti-framework” type problems. Sometimes things are just…hard. In those situations, it’s important for leaders to stay true to their values, safeguard the company’s vision / mission, and…just keep moving forward. Particularly in situations with no seemingly pleasant options, overly analytical mental models rarely help. Instead, they can delay the inevitable and prolong the agony for all involved. Better for leaders to pull their socks up, and just get on with it.

Art & Science: Some aspects of SaaS businesses are clearly more science than art (examples include financial bookkeeping, constructing entrance / exit criteria for sales stages, and collecting statistically valid NPS data from customers). Still, others are a blend of art and science. For example, we can use a carefully researched product framework to help empathize with, and prioritize input from, customers (science). But it’s a far more artful endeavor to incorporate that input into a brand that faithfully captures the essence and a resonant market-promise that we want to non-verbally convey to all stakeholders. Art doesn’t need a framework; art needs to touch-off the right note in people’s System 1 brains. Note of disclosure: We admittedly do use a number of frameworks to assist in a carefully considered re-branding process. But at a certain point, it’s all about the output and not at all about the process imbued through framework-type thinking.

Unique Problems: It’s been written that “there is nothing new under the sun.” And while I won’t debate this point on a fundamental level, there are exceptions in small-scale SaaS businesses. Although there are a finite number of moving parts in SaaS businesses, fact-patterns often arise for companies, where they are facing challenges that present themselves in completely new and unique ways. For these situations, frameworks are relatively helpful; rather creativity is required. I’m reminded of a platform-upgrade and related migration challenge that we experienced at one SaaS business. The SaaS world has seen countless upgrades / migrations, so we looked to past precedent and roadmaps to inform the initiative. But the specific combination of business context / use-case idiosyncrasies / uptime requirements / seasonality of our customers demanded that we establish a completely unprecedented approach to the migration. A mixture of creativity and ruthless pragmatism carried the day; frameworks were unhelpful.

Make to Scrap: Software is all about efficiency, and we SaaS leaders hate re-creating the wheel. With this in mind, we err toward thoughtfully building our products and processes with attention to ensuring scalability and re-usability. But some situations demand speedy action for a pressing moment, with little thought to future needs. This might mean spinning up a (true) MVP, filling an urgent personnel need with outside resources, or addressing a surprise market condition with a one-time targeted offering. In any of these cases, one-time-only action may trump frameworks.

In closing, and to be clear, mental models greatly assist SaaS operators in countless situations. But it’s also important for SaaS leaders to leave room in their brain to recognize those less frequent situations when frameworks are less helpful, possibly even counter-productive. Where fortitude, creativity, speed, and situational decisiveness are what’s needed most…not everything needs to be a F8*%^&! framework.

“Digital transformation is a foundational change in how an organization delivers value to its customers.” -CIO

“Digital transformation is the process of using digital technologies to create new — or modify existing — business processes, culture, and customer experiences to meet changing business and market requirements.” -Salesforce

“The essence of digital transformation is to become a data-driven organization, ensuring that key decisions, actions, and processes are strongly influenced by data-driven insights, rather than by human intuition.” -Harvard Business Review.

Digital transformation is clearly a hot topic that is top of mind for many business leaders. But for small-scale SaaS businesses, digital transformation can feel like something foreign that “doesn’t really happen here.” Maybe this is because the topic is often portrayed as being unimaginably massive in its scope and implications (per the above quotes); whereas growth businesses must focus near-term. There’s also a “feast or famine” aspect to this depiction; it implies that digital transformation is best suited to either (1) old-school industries with a pressing need to modernize-or-die (the “famine” camp), or (2) highly capitalized, bleeding-edge tech firms pursuing reality-bending innovations (the “feast” cohort). Neither is typically the case in small-scale SaaS businesses, nor is this positioning particularly helpful. Rather, we observe digital transformation within small software companies as taking place one step at a time; and it helps to avoid overthinking it. In this way, digital transformation looks less like otherworldly “foundational change” and more like workflow automation that is pragmatic, targeted, and high-impact. Below are some simple examples from the real-world of Lock 8’s portfolio companies, followed by a few takeaways from these cases.

Marketing and Sales:

Product and Client Success:

These examples help illustrate a few key takeaways related to digital transformation. First, purists would likely argue that the above are all pedestrian / tactical in nature; and they don’t truly represent digital transformation. Fine — potato // po-tah-to. As long as they contribute to meaningful advances in our ability to execute, we don’t care what they are called. Second, tackling such minor improvements is habit-forming. We’ve found that implementing each of these small improvements tends to reveal other worthwhile processes that can be enhanced with minor automation. Third, every aspect of the business is a candidate for such project-lets. The examples above focus on a few departments, but we’ve seen a focus on Sales and Marketing (for example) very quickly shed light on potential workflow changes in Finance, HR, and other parts of the business. And, finally, we’ve found this works best when everyone is invited to play in this game. There may be one person who is particularly talented in business systems — and that person can lead execution — but process improvement ideas need to come from anywhere and everywhere within the org.

Just as every great journey begins with a single step, the road to digital transformation starts with some simple workflow automation — don’t overthink it.

A prior post made the case in favor of hiring first time CEOs to lead small-scale SaaS businesses; and this piece picks up where that one left off. Specifically, it expands on characteristics to prioritize when screening CEO candidates, some questions to help assess them, and — most importantly — ways to support executives in deepening those attributes once they are in-seat as CEOs.

Per that earlier post, “We prioritize candidates with high levels of humility / coachability, EQ (emotional quotient), systems-thinking, and prioritization skills; and the odds of their success are greatly improved by supporting them in an intentional, structured, and consistent way.

These supporting activities are critical: it is perfectly reasonable to ask rookie CEOs to lead effectively; but it would be naïve to ask them to do so without a support network or a shared commitment to their ongoing development. This post shares what that support can look like in practice by diving into “what / why / how” behind these particular characteristics and how fostering them can help position CEOs for success.

I. Humility / Coachability

II. Emotional Quotient

III. Systems Thinking

IV. Prioritization Skills

In sum, these characteristics are critical to help first time CEOs survive. And, while we certainly test for them in the interview process, we spend a lot more time and energy in helping to support the ongoing development of those attributes in CEOs over time.

A quick closing aside: these characteristics are crucial as CEO differentiators; separating the good from very good. They are “spices” that makes the meal compelling and something of unique value. The “main dish,” though, is comprised of a core set of must-haves that were summarized in a prior post as an exec’s ability to (1) Get it, (2) Want it, and (3) Capacity to do it. This latest post does not intend to suggest ignoring or in any way under-valuing such must-haves. Admittedly, without these staples, those spices would be wasted and without substance.

Last week I had the opportunity to speak with three different SaaS execs about their careers. Each had valuable experience within high-growth software businesses. Each brought deep management and functional experience, having led critical departments within their respective companies. Each presented themselves as personable, passionate, and articulate about their work. And yet, they were all grappling with how to take the desired next step of their career journeys — to land the CEO gig at a growing SaaS business.

These folks are not alone; countless aspiring leaders struggle to make this leap. This is unsurprising: although many executives harbor the lifelong dream of leading a company, the chief executive role is uniquely challenging; and the sheer numbers are stacked against elevating to this level. Likewise, seemingly everyone wants to get in on SaaS these days, making the odds even longer for would-be tech leaders. And yet, making the jump to SaaS CEO is far harder than it should be. In fact, like many things in life (such as college admissions, securing student internships, earning a roster spot on competitive teams), the “right to enter” can be even more prohibitive than the required qualifications to succeed. Why is that?! This post aims to identify, and hopefully poke a few holes in, some of the less obvious reasons for why it is so hard to navigate the path to becoming a SaaS CEO.

The Founders Path: The surest path to becoming CEO of a SaaS business is to start one. Again, this is unsurprising: founders are the natural choice to lead the entrepreneurial endeavors they initiate. After all, who better to rear the brainchild than the person who hatched the idea in the first place? This founder-as-CEO model has been reinforced for decades in our minds by the many well-known and truly remarkable individuals who have not only started successful businesses, but also subsequently led them through extended periods of growth. Thomas Edison, Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, Jack Ma, Payal Kadakia, and countless others have made this extraordinary achievement seem almost commonplace — it’s not. It is rare and amazing, and it should be celebrated as such. And yet, founders often remain CEO of their business until either (a) the business goes belly-up (bad outcome, but statistically the likeliest), or (b) the business succeeds and grows to the point of needing a hired-gun executive (good outcome, but often an emotionally fraught one).

This whole dynamic can be cruelly ironic in a couple ways. First, a fair portion of founders end-up learning that have little appetite for many of the CEO’s duties (such as: leading people, managing a board, exec selling, or sweating the financials). Rather, founders often prefer to start things…not finish them. Conversely, many executives yearn for the top-spot in a company and have invested heavily in developing related skills…but simply don’t possess the founder-gene. Consequently, one of the most viable paths to becoming a SaaS chief executive is blocked to countless qualified leaders simply because they “don’t have a great idea for starting a business.” As a short aside, many would-be CEO’s do end up choosing to start businesses, at least in part as an entrée into the corner office. Although this absolutely can work out well, it is generally a “tail-wagging-the-dog-ish” bad idea. Anyway…where exactly does this leave the non-founder SaaS exec who has the itch to prove herself in the CEO role?

Which Came First? For non-founders, the obvious route to “CEO-dom” is to work one’s way up the ranks. Unfortunately, this is also a narrow path with many pitfalls, including the fact that climbing the corporate ladder can take years or decades (with plenty of brain-damage and no guarantees along the way). To further complicate matters, not many employers actively recruit non-founder, first-time CEO’s. Traditional VC / PE investors, who often are responsible for hiring SaaS CEO’s, rarely (if ever) actively seek out rookie CEO’s. Again, hardly surprising: these financial stakeholders have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize returns while minimizing risk. Accordingly, very few are keen to take a chance on an unproven executive in the one role that will arguably have the greatest impact on the outcome of a given investment. Likewise, self-aware founders seeking to replace themselves generally tend to prioritize a proven track-record when considering their successors — and certainly not less-experienced first time CEO candidates! All of which begs the question: if one needs to have already been a CEO to become a CEO…how does one initially break-in? That is precisely the vexing chicken-and-egg problem that the executives described above are striving to crack.

The hard truth is that — like so many things in life (e.g. skydiving, performing in a live production, asking someone out on a date) — no training can adequately prepare CEO’s for the real thing. Sure, aspiring CEO’s could / should strengthen their CV by amassing increasing levels of leadership experience and developing valuable functional expertise. Sales, marketing, finance, and product management are all proving grounds for future chief executives. General management roles, particularly ones with accompanying P&L responsibility, are also “as good as it gets” in terms of prepping future SaaS CEO’s for the stress and complexity of “sitting in the big chair.” But even with such undeniable preparation, the first-time CEO remains about as appealing as an understudy on Broadway — highly suspect unless and until he / she demonstrates the ability to handle the moment and shine when the lights come up. These and other forces combine to create a stacked deck against aspiring CEO’s. But this doesn’t have to be the case.

Contrarian Closing: Why we like first-time CEO’s

With respect to all of the points above, we beg to differ. When it comes to early-stage SaaS businesses, we dig first-time CEO’s. While there are many undeniable benefits of prior CEO experience, there is also a lot to like about first-time CEO’s in this environment. First, they tend to be quite energized by the opportunity to “make something their own.” This typically translates into a high “want-to” factor, the importance of which simply can’t be overstated (as outlined here). This is particularly true when a leader marries that enthusiasm with a high-level of capacity / competence, which is overwhelmingly characteristic of anyone who is a legitimate CEO candidate. As another short aside, this point reminds me of this gem from Simon Sinek…so, so true). First-timers also tend to have a healthy respect for the complexity of the role / situation into which they are stepping. This encourages them to be open-minded and coachable; and it discourages them from prescribing before diagnosing. This is a crucial point; some of the biggest mistakes leaders make can result from defaulting to the assumption that they’ve already “seen this movie” (aka: fully understand a situation, before having completed exhaustive discovery). Rookies, on the other hand, rarely fall into this trap. Finally, sub-scale SaaS businesses tend to be scrappy and under-resourced; and first-time CEO’s can easily jump-in with both feet. Specifically, they are in a great position to leverage up-to-date expertise that draws on their functional background…and, in the process, to help the business punch well above its weight.

In fairness, not all departmental / functional leaders can successfully make the leap to CEO. We prioritize candidates with high-levels of humility / coachability, EQ (emotional quotient), systems-thinking, and prioritization skills; and the odds of their success are greatly improved by supporting them in an intentional, structured, and consistent way (both of which seem like topics for future posts).

In sum, though, up-and-coming execs can offer a great option as CEO’s of sub-scale SaaS businesses…much more so than is suggested by the narrow paths available for them to get there.

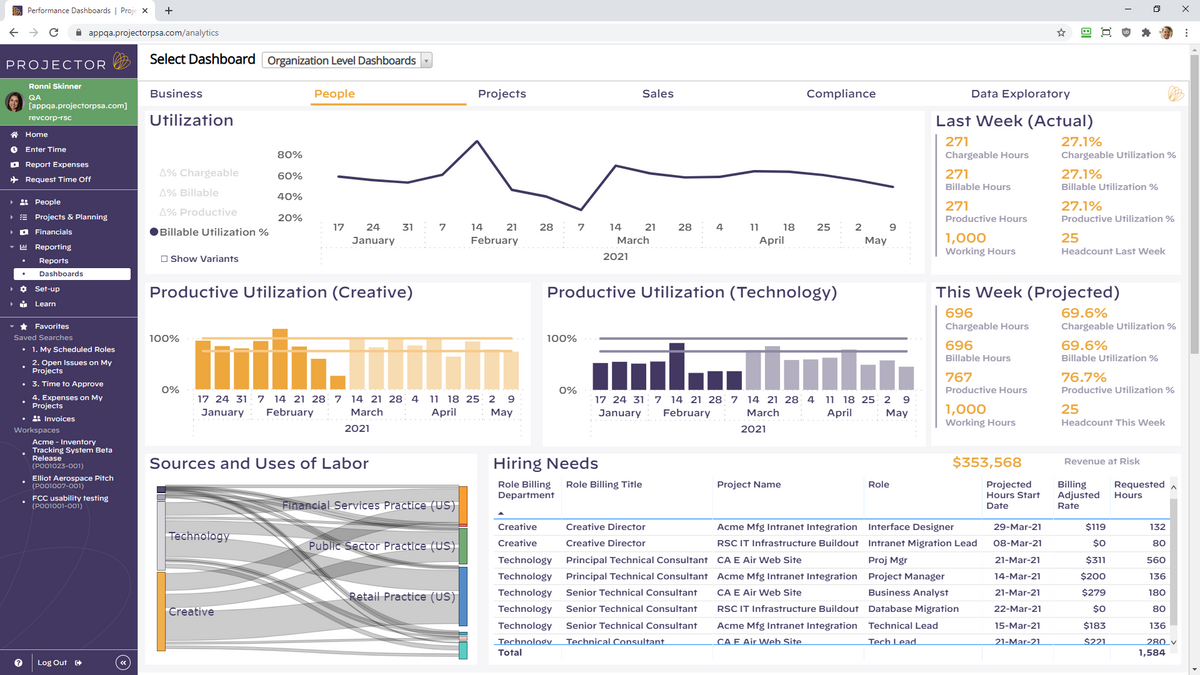

I recently wrote that business dashboards are instruments of control. That observation and the related post, while hopefully helpful, made some general assumptions in discussing dashboards. So, this post takes a crack at addressing an ongoing open point about the existential nature of dashboards: what exactly is their purpose?

Although Stephen Few provides an excellent definition, it leaves room to debate dashboards’ ultimate objective.

Definition: A dashboard is a visual display of the most important information needed to achieve one or more objectives; consolidated and arranged on a single screen so the information can be monitored at a glance. — Stephen Few

Our observation is that the primary purpose of most dashboard initiatives lies somewhere between two general approaches, which can be loosely described as Reporting on one end of a spectrum, and Analytics on the other. The problem many operators face is that their efforts can wind-up betwixt and between the two, often without even realizing it. These two poles offer useful guardrails when considering the objective of any dashboard initiative; and examining and choosing between them helps to clarify many aspects of that dashboard. This kind of clarity, in turn, can help align and ultimately exceed stakeholder expectations.

Five seemingly simple (but deceptively challenging) questions offer a good start toward getting people on the same page:

Although they’re a good start, these questions can admittedly be a bit opaque for practical application. To make them more actionable, we expanded the questions into a “quasi-diagnostic” table. This table captures attributes and examples of each approach, to help leaders identify and intentionally choose how best to prioritize and proceed.

Identifying these characteristics and having open conversations about each can certainly de-mystify the purpose of dashboards and put an organization in a better position to optimize its time and resources.

A few caveats / qualifiers / comments about the above:

In closing, it seems worth following-up with one of my favorite go-to questions: So what? Why does the debate about dashboards’ purpose even matter?! Quite simply, intentionality matters when it comes to metrics measurement. Contrary to popular lore, it’s not so much that “what gets measured gets managed;” Danny Buerkli does a great job debunking that familiar trope here. Rather, as Buerkli succinctly argues, “Not everything that matters can be measured. Not everything that we can measure matters.” So true. And because sub-scale SaaS businesses operate in a world of big dreams but small teams, focus is our friend. Like any other product or service, dashboards should have a clear approach, objective, and target stakeholder…lest they lose their incisiveness and value. So, when considering dashboards, as with all things related to business building — choose wisely and with intent.

I’ll admit that I love a good dashboard. As an aid to SaaS operators seeking to optimize business performance, dashboards can be invaluable.[1] Stephen Few defined a dashboard as, “a visual display of the most important information needed to achieve one or more objectives; consolidated and arranged on a single screen so the information can be monitored at a glance.” This is a useful definition that makes clear: dashboards are instruments of control. Specifically, just as dashboards within vehicles aid in the controlled navigation of those machines, company dashboards help leaders drive organizations forward while controlling speed, direction, and business health. And yet…the irony of dashboards is that before advancing any aspects of a business, sacrifices must first be made in the very same areas that leaders seek to optimize. To go fast, you must first go slow. To go far, start with steps backward. To increase control, make a conscious decision to loosen oversight.

With these contradictions in mind, this post strives to flash a warning light (see what I did there?) by dispelling any illusions leaders may have about scoring easy wins with dashboards. Rather, it introduces some questions to ponder and detours to explore when considering dashboard initiatives. Hopefully these will help folks achieve the goal of getting past the entry-ramps and using dashboards to confidently drive the business forward in the fast lane.

Control: This is What Democracy Looks Like? Advocates of dashboards sometimes tout them as nobly delivering democratization of data. But do dashboards inherently reinforce the notion of one person, one vote? Not necessarily (the term “executive dashboard” seems to succinctly refute this point). Rather, a key question to be answered early in a dashboarding effort centers around data roles, rights, and privileges. Who gets access to what data? Is the dashboard’s audience the CEO? The Leadership Team? Every team member within a business (including / excluding contractors and consultants)? Should there be a curated / filtered set of data for each? Oh, and, what about the board of directors?

A related question centers on how dashboard information is consumed — on a push or pull basis? Purists might argue that dashboard users should be able to “pull” information. That is, they should be able to access what they want, when they want it, and manipulate the information to suit their needs. The problem, of course, is that this is horribly inefficient and variable — we humans rarely know what we want until someone presents it to us as a solution to our needs. That view supports the position of what I call “curators” who believe dashboards are best served up on a push basis. In an extreme version of this model, some analyst-type packages up KPI’s into a report and shares it with a defined set of stakeholders on an agreed-upon cadence. This approach is certainly efficient / prescriptive, but not at all a beacon of data democracy.

My own experience here is that the middle is marvelous. Dashboard information is most valuable when shared broadly with a large number of stakeholders and with minimal access constraints. But the dashboard should also be structured and streamlined, not just a filtered database that can be used to spin-up infinite ad-hoc reports (after all: if everything is important, then nothing is). Finally, regularly scheduled all-hands reviews of the dashboard by company leaders are key to offering commentary and context. This helps provide all stakeholders with a clear understanding of “what matters, how we’re doing in those areas, and what each of us can do about it.” In this way, leaders can absolutely gain more control over their business through dashboards. But they must first be prepared to loosen the reigns on potentially sensitive data and to make themselves vulnerable by sharing it (in good times and bad). I’d argue this approach doesn’t represent a pure (data) democracy, but perhaps it is more like a high-functioning (information) republic.

Speed: Slow is Smooth, and Smooth is Fast: This useful adage from the Navy SEALs has been widely analyzed (e.g. here, here, and here). The general gist is that “the best way to move fast in a professional setting is to take your time, slow down, and do the job right.” This is particularly prescient in connection to implementing business dashboards. As leaders, we want dashboards to serve as an accelerant: to provide early alerts about deviations versus plan, to streamline our decision-making, and to speed the pace of collective results. But…to go fast, we need to start slow. A big-bang approach simply doesn’t work when creating dashboards. Never have I seen a version 1.0 dashboard that was worth a darn. In fact, “if you move too quickly, you bump and bounce and veer from that path because you are frantic, trying to do too many things at once.” Rather, a deliberate and iterative approach to creating dashboards allows leaders to test, learn, adapt, and develop a dashboard that truly serves the needs of the business — over time.

A corollary to leaders’ “need for speed,” is the desire to automate the updating of dashboards. Like a scene from Minority Report, the dashboards in our imaginations should miraculously and effortlessly pipe future-illuminating intelligence directly to our brains on a continuous loop. It’s a compelling vision; and automated updates to dashboards are totally doable — eventually. But a fair degree of manual work is necessary to get a dashboard stood-up. Manual data-entry (the antithesis of tech-enabled efficiency) is often required at the outset of a project, particularly in the early iterations described above. Even after graduating from data-entry, labor is needed to enable efficient and error-free data feeds from different company systems. It. Just. Takes. Time.

In my view, balance is helpful in navigating the tension between slow and fast. Having botched overly ambitious dashboard initiatives, I’ve learned to start small and slow. It’s wise to avoid throwing out an otherwise valuable metric, simply because it is hard to collect — report what matters to the business, even if it requires manual data entry. Conversely, don’t prioritize the automation of data collection early in a dashboarding effort. Doing so can mean “letting the great be the enemy of the good;” and technical glitches have killed countless promising projects. One of my all-time favorite dashboards (a snippet of which is included below) took 18 months to get right. Initial versions were brutally tedious to update — manually. And even in its prime, it was never visually impressive. But, by taking our time, we eventually created an astonishingly valuable tool that helped accelerate the business.

Horizon: Is Real-Time Really the Best-Time? Another common hope among leaders is for dashboards to help predict the future. This translates into wanting to (a) report the most up-to-date information and (b) measure that information in shorter and shorter chunks of time — by month, week, day, hour, and even by the minute. This works well for many metrics, where recency really matters. For SaaS businesses, such metrics might include website visitors, numbers of qualified leads, product usage metrics, or volumes of support tickets.

But other metrics evolve on a slower cadence; and measuring them over short time horizons is less helpful. As a correlate, I’m reminded of the recommended method for taking one’s pulse: top medical organizations advise counting someone’s pulse over a 60 second span. Although it would be a lot more efficient to measure someone’s pulse for only 2 seconds and then multiply the result by 30…that would give a far less accurate reading. Similarly, many metrics in SaaS businesses require measurement over a longer period, lest the results be useless or misleading. This is particularly true in enterprise businesses selling large dollar subscriptions over long sales cycles. In such cases, one week’s worth of data can have very limited utility; rather, we need to see data over a quarter or even multiple quarters. Examples of these longer-lead metrics include: sales and marketing conversion rates, contracted new bookings performance, measuring execution against hiring plans, or quantifying employee engagement. All of these tend to take a long time to materialize and are inherently “lumpy” in nature.

Where this can lead to dashboard-related trouble is when we try to measure all metrics on a uniform cadence over consistent time horizons. Rather, leaders need to approach dashboard projects with realistic views on just how real-time their measurements should be…and apply time horizons unevenly across different metrics.

To further complicate this issue, today’s results are often best interpreted by looking backward in time. This is challenging for many reasons. First, we often don’t have access to good historical data, which is commonly the motivating factor behind the dashboard project in the first place. Looking backward in this way also contradicts every instinct of the future-focused leader who has undertaken a dashboard project for the stated purpose of more proactively looking ahead. While real-time data is certainly appealing, successful dashboard efforts must also consider both current and past data over long time-horizons.

Conclusion: In sum, dashboards can yield valuable results for businesses and offer great benefits to thoughtful business leaders. Specifically, they can increase the control, speed, and foresight with which the business operates. But none of these benefits comes without a cost. And that price is often paid in the form of leaders first making sacrifices, or investing time and resources, in the very same aspects of the business that they wish to ultimately optimize.

Footnote:

[1] Dashboards are also imperfect and highly variable, as argued well here and here.

As he does in his blog with astonishing frequency, David Cummings last week put his finger on a pervasive problem in startups: complexity of messaging. To cap-off a characteristically well-constructed case for communicating with simplicity, the post concludes with this guidance to operators: “The next time you describe your product, competitive position in the market, or value add, reduce the complexity of the verbiage. Increase the understandability. Make it clear.” Such great advice; and I’ve been thinking about it all week. But, like many things in life, it is easy in theory // difficult in practice. So, I’ve tried here to stand on the shoulders of a giant, and offer 10 tips & tricks that we’ve employed in our own efforts to follow David’s counsel toward clear messaging:

In short: David Cummings was dead-right — in terms of company messaging, make it clear! Hopefully these tips make it a bit easier to do so.

In September of 2020, I attended SaaStr Annual and wrote about it here. It was my first fully virtual multi-day conference; and there was a real novelty factor to it. Seven months and several digital conferences later, I’ll admit to eagerly awaiting the return of in-person industry events. Still, I was pretty fired-up to take part in SaaStr Build this week; and it did not disappoint. The return on my time-invested was high, with a mix of valuable takeaways and follow-up research to do. My hope in this post is to succinctly share some of my personal highlights with anyone interested but unable to attend the event. Specifically, below are 5 content takeaways and 5 general observations, hopefully in under 5 minutes of reading. Ready…go.

CONTENT:

GENERAL REFLECTIONS:

Parting Thought: To make up for having cheated above, I’ll add one last point. I commented in September on the general air of uncertainty at that time and the silver lining at SaaStr Annual of a related (and welcome) vibe of community / humility among attendees. With SaaS multiples at all-time highs, that uncertainty seems to have been replaced with open bullishness at SaaStr Build; and the event certainly offered ample grounds for optimism in the space. My hope for the SaaS community in the coming quarter+ is that we continue to experience sustained market strength…AND / BUT that the same sense of community also endures. Here’s to 2021.