At Lock 8 Partners we spend a lot of time chatting with, and learning from, operators of SaaS businesses. It was in that context that I began trading notes with James Marshall mid-way through the pandemic. In addition to having an impressive track record of leading sales teams, James has generously shared with me his thoughtful views on the never-ending evolution of sales teams. It was on this topic that James and I recently collaborated; and he was kind enough to codify some of his thoughts. Thanks, James, for contributing the following post to the Made Not Found blog!

___________________________________________________________________

Introduction:

SaaS sales leaders find themselves in a crucible chapter for B2B sales, as the pandemic has accelerated trends that pressure sales leaders to modernize. To outperform their competition, the best sales leaders will embrace both the 1) digital transformation of their sales organization and 2) the evolution of their sales processes. Although these may sound like daunting endeavors, there are a few easy wins that can have an immediate impact.

Covid-19 and the Battle for Talent:

A limited talent pool and increased competition for candidates is driving sales into a stage of discomfort. Prior to Covid-19, the recruiting battle for sales professionals was already stretching a limited pool of sales talent; and the pandemic has greatly accelerated this trend. Through the normalization of remote work, North America’s hottest tech centers are now empowered to recruit outside their city limits for perhaps the first time in their existence. Fueled by historically sky-high valuations, tech companies from North America’s hottest startup zones have an edge in the battle for a limited talent pool. Put simply, that enterprise sales rep in Knoxville, TN who could historically be recruited by their local startup ecosystem for a $225k OTE (on-target earnings), is now entertaining job offers from Silicon Valley and Austin, TX for $350k OTE.

Technology companies everywhere are being forced to compete for this talent and increase wages for salespeople. However, sales productivity metrics aren’t changing nearly as quickly as a reps’ base salaries. We all know that high OTE’s mean correspondingly high quotas. Studies done by Salesforce have shown that more salespeople expect to miss their FY sales quotas than attain them. According to Gartner, only 6% of Chief Sales Officers are extremely confident about meeting their revenue goals in 2021.

Sales Productivity Must Increase:

It goes without saying that against this backdrop, sales productivity must increase. Fortunately, there is some fruit — while not quite low hanging fruit — that is within reach for businesses that take the time to revisit their sales process. These advantages are found through unlocking the combined benefits of sales technology platforms and sales process innovation.

Platforms: The Digitally Enabled Rep

While it’s often said that today “every business executive is a technology executive,” too often sales leaders have lagged behind their peers. Whereas 84% of marketing teams leverage AI, just 37% of sales teams do. And of that 37%, I commonly observe sales teams with access to a wide array of tools (e.g. an outbound automation platform, a contact database tool, a conversational intelligence platform, Sales Navigator, a video prospecting platform, and a myriad of great plugins for their CRM), but where team productivity is undermined by low user adoption.

Yet the data is clear: companies that leverage AI-driven sales platforms outperform those who don’t. Whereas 57% of top-performing sales teams leverage AI-empowered sales platforms, only 31% of moderate performers and 20% of low-performers leverage AI in their sales process.

Contributing factors to this low-adoption stem from leadership’s comfort level with sales technology. We commonly observe that sales leaders themselves haven’t made the jump into tech-enabled selling. As a result, many 1) don’t feel comfortable coaching their teams to utilize these technologies as part of their sales processes, and 2) purchase technology without accounting for the sales rep’s user experience.

The great news is that SaaS ecosystem for sales has innovated well beyond the current state of its user community. The best sales leaders will evolve their sales processes to support robust utilization of these products, which will bolster their sales reps’ productivity. The return on this investment is swift and certain. More on this in a future post.

Modernize the Sales Process:

The typical B2B SaaS marketing department has evolved to be the data-driven, tech-enabled functional area that it is today. Conversely, the enterprise field-sales process has evolved very little since the industrial age. In the late 19th and early 20th century, John Rockefeller’s Standard Oil ran a large field sales organization where geographically based salespeople opened new accounts and grew existing ones. Unfortunately, the pace of change in our complex world makes it extremely difficult for today’s reps to “do it all,” as their predecessors did. If that sounds like your company’s sales process, I rest my case.

As an alternative, many successful companies divide the sales responsibility into two and three parts (BDR, AE, and to some extent Customer Success). However, even these models fall short of 1) breaking down the motion of sales-led growth into its simplest parts, and 2) assigning those parts to the most competent and cost-effective people and platforms to execute them.

As a quick illustration, let’s look at how a salesperson spends their time and assign a dollar value to their daily tasks. For the sake of argument, we’ll say that this is a “Field Salesperson” who is receives $250k of annual compensation in exchange for 45 hours of their time and attention each week. At $115 an hour, the business has no doubt hired this person for their ability to sell large deals. Yet in 2018, salespeople reported spending just one-third of their time actually selling. The culprit? Data entry is certainly one of them; and in the case of our example rep, date entry comes at a cost of nearly $700 per day. And, that figure comes before we’ve started analyzing how much time a rep spends on building lists, outbound prospecting, creating sales collateral, etc.

By neglecting the work of sales process innovation, companies are overpaying for customer acquisition. We’ve found that clearing the calendar for even one day of planning often allows sales leaders to identify targeted areas for process improvements that shorten the sales cycle and / or lower CAC.

Many startups and small companies will argue that while this kind of role-specialization would be ideal, they are too small to capitalize on it. Fortunately, the white-collar gig economy is stronger than ever through websites like Upwork and Fiverr. Through some simple privacy accommodations, startups are able to utilize this outsourced talent pool, while quickly segmenting their sales process and increase their effectiveness.

Conclusion:

In this environment of increasing expectations, sales leaders have two levers which are well within reach. Sales leaders will gain a competitive advantage by 1) driving user adoption from the rich ecosystem of sales automation technologies available, and 2) analyzing their sales process for opportunities to innovate. Today, it’s not hyperbole to say that any startup or midsize SaaS company is just a few tweaks away from unleashing a force of digitally enabled salespeople who are focused on executing their highest-impact revenue activities. When that happens, everybody from salespeople to investors win.

At our pre-wedding rehearsal dinner, one of the groomsmen made the following toast: “A person is judged by the company they keep. And, although I’m not all that crazy about Todd, his friends are truly amazing!” It was one of the best compliments I’ve ever received.

In the 20-something years since, that dynamic persists: I’ve been fortunate to meet, collaborate with, learn from, and befriend many remarkable people in and around small-scale SaaS businesses. Some of them have generously shared their wisdom on this blog (such as here and here). Today that practice continues with some sage advice from Robert Morton.

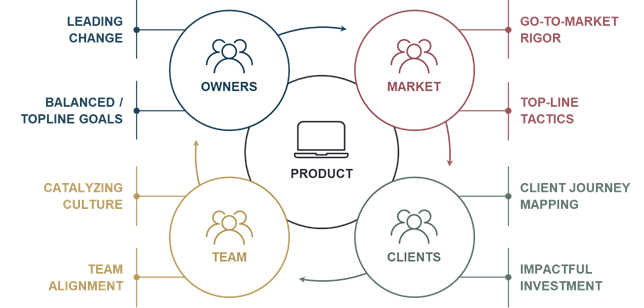

I met Robert during our shared time at Blackboard; and now the guy just can’t shake me. A true lifelong learner, Robert has continued to expand his formidable skills and push the boundaries around how to build durable businesses and relationships. He recently hung up his own shingle as a growth and customer insight / experience consultant at Highland Advisors (full disclosure, Lock 8 is a proud client). He also recently wrote passionately about the concept of consequentialism as it relates to customer experience. With Robert’s blessing, I share those thoughts below. Thank you, Robert; here’s to consequentialism:

Every time I read another company drone on about “we strive to put customers first”… only to follow with some weasel-ey, anti-customer move, I’m reminded just how badly most outfits need a dose of consequentialism. A mouthful of a word but the gist is this…

Your intent doesn’t matter, what’s in your company heart doesn’t matter… there’s just your actions and what they result in.

If the move you’re making improves customer value, it’s a customer centric move.

If the move you’re making chips away at customer value, it’s an anti-customer move.

That’s it. What you mean, or how well you wax poetic about your customer-centered beliefs, doesn’t count. In this view there are just actions and a tally of outcomes over time that add up to a more customer-centric or more anti-customer bearing as a company.

Over-simple? Maybe. Isn’t intention a mark of seriousness and care in the approach to just about anything? Perhaps.

But I’ll wager we’d have better customer outcomes, with a lot more impact per word, if we at least passed a consequentialist lens over all the customer (employee too, likely) moves we make.

No self-soothing with noble intents or rationale gymnastics allowed. Just the cold light of asking ourselves “is the outcome of this thing we’re planning customer-centric or anti-customer”? And if the latter, “how do we feel about that, what do we want to do about it”?

And if you believe as I do that the conversations you have shape the culture you have, simply posing and wrestling with these questions in the open carries its own very powerful reward.

Because when we do, we change the accepted language and conversation of our orgs. Turning more of our everyday work gabs into open development discussions about the customer (or employee) experience we want to make here.

And that, more than any single CX decision we end up making, may be the most consequential move of all.

A prior post made the case in favor of hiring first time CEOs to lead small-scale SaaS businesses; and this piece picks up where that one left off. Specifically, it expands on characteristics to prioritize when screening CEO candidates, some questions to help assess them, and — most importantly — ways to support executives in deepening those attributes once they are in-seat as CEOs.

Per that earlier post, “We prioritize candidates with high levels of humility / coachability, EQ (emotional quotient), systems-thinking, and prioritization skills; and the odds of their success are greatly improved by supporting them in an intentional, structured, and consistent way.

These supporting activities are critical: it is perfectly reasonable to ask rookie CEOs to lead effectively; but it would be naïve to ask them to do so without a support network or a shared commitment to their ongoing development. This post shares what that support can look like in practice by diving into “what / why / how” behind these particular characteristics and how fostering them can help position CEOs for success.

I. Humility / Coachability

II. Emotional Quotient

III. Systems Thinking

IV. Prioritization Skills

In sum, these characteristics are critical to help first time CEOs survive. And, while we certainly test for them in the interview process, we spend a lot more time and energy in helping to support the ongoing development of those attributes in CEOs over time.

A quick closing aside: these characteristics are crucial as CEO differentiators; separating the good from very good. They are “spices” that makes the meal compelling and something of unique value. The “main dish,” though, is comprised of a core set of must-haves that were summarized in a prior post as an exec’s ability to (1) Get it, (2) Want it, and (3) Capacity to do it. This latest post does not intend to suggest ignoring or in any way under-valuing such must-haves. Admittedly, without these staples, those spices would be wasted and without substance.

Last week I had the opportunity to speak with three different SaaS execs about their careers. Each had valuable experience within high-growth software businesses. Each brought deep management and functional experience, having led critical departments within their respective companies. Each presented themselves as personable, passionate, and articulate about their work. And yet, they were all grappling with how to take the desired next step of their career journeys — to land the CEO gig at a growing SaaS business.

These folks are not alone; countless aspiring leaders struggle to make this leap. This is unsurprising: although many executives harbor the lifelong dream of leading a company, the chief executive role is uniquely challenging; and the sheer numbers are stacked against elevating to this level. Likewise, seemingly everyone wants to get in on SaaS these days, making the odds even longer for would-be tech leaders. And yet, making the jump to SaaS CEO is far harder than it should be. In fact, like many things in life (such as college admissions, securing student internships, earning a roster spot on competitive teams), the “right to enter” can be even more prohibitive than the required qualifications to succeed. Why is that?! This post aims to identify, and hopefully poke a few holes in, some of the less obvious reasons for why it is so hard to navigate the path to becoming a SaaS CEO.

The Founders Path: The surest path to becoming CEO of a SaaS business is to start one. Again, this is unsurprising: founders are the natural choice to lead the entrepreneurial endeavors they initiate. After all, who better to rear the brainchild than the person who hatched the idea in the first place? This founder-as-CEO model has been reinforced for decades in our minds by the many well-known and truly remarkable individuals who have not only started successful businesses, but also subsequently led them through extended periods of growth. Thomas Edison, Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, Jack Ma, Payal Kadakia, and countless others have made this extraordinary achievement seem almost commonplace — it’s not. It is rare and amazing, and it should be celebrated as such. And yet, founders often remain CEO of their business until either (a) the business goes belly-up (bad outcome, but statistically the likeliest), or (b) the business succeeds and grows to the point of needing a hired-gun executive (good outcome, but often an emotionally fraught one).

This whole dynamic can be cruelly ironic in a couple ways. First, a fair portion of founders end-up learning that have little appetite for many of the CEO’s duties (such as: leading people, managing a board, exec selling, or sweating the financials). Rather, founders often prefer to start things…not finish them. Conversely, many executives yearn for the top-spot in a company and have invested heavily in developing related skills…but simply don’t possess the founder-gene. Consequently, one of the most viable paths to becoming a SaaS chief executive is blocked to countless qualified leaders simply because they “don’t have a great idea for starting a business.” As a short aside, many would-be CEO’s do end up choosing to start businesses, at least in part as an entrée into the corner office. Although this absolutely can work out well, it is generally a “tail-wagging-the-dog-ish” bad idea. Anyway…where exactly does this leave the non-founder SaaS exec who has the itch to prove herself in the CEO role?

Which Came First? For non-founders, the obvious route to “CEO-dom” is to work one’s way up the ranks. Unfortunately, this is also a narrow path with many pitfalls, including the fact that climbing the corporate ladder can take years or decades (with plenty of brain-damage and no guarantees along the way). To further complicate matters, not many employers actively recruit non-founder, first-time CEO’s. Traditional VC / PE investors, who often are responsible for hiring SaaS CEO’s, rarely (if ever) actively seek out rookie CEO’s. Again, hardly surprising: these financial stakeholders have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize returns while minimizing risk. Accordingly, very few are keen to take a chance on an unproven executive in the one role that will arguably have the greatest impact on the outcome of a given investment. Likewise, self-aware founders seeking to replace themselves generally tend to prioritize a proven track-record when considering their successors — and certainly not less-experienced first time CEO candidates! All of which begs the question: if one needs to have already been a CEO to become a CEO…how does one initially break-in? That is precisely the vexing chicken-and-egg problem that the executives described above are striving to crack.

The hard truth is that — like so many things in life (e.g. skydiving, performing in a live production, asking someone out on a date) — no training can adequately prepare CEO’s for the real thing. Sure, aspiring CEO’s could / should strengthen their CV by amassing increasing levels of leadership experience and developing valuable functional expertise. Sales, marketing, finance, and product management are all proving grounds for future chief executives. General management roles, particularly ones with accompanying P&L responsibility, are also “as good as it gets” in terms of prepping future SaaS CEO’s for the stress and complexity of “sitting in the big chair.” But even with such undeniable preparation, the first-time CEO remains about as appealing as an understudy on Broadway — highly suspect unless and until he / she demonstrates the ability to handle the moment and shine when the lights come up. These and other forces combine to create a stacked deck against aspiring CEO’s. But this doesn’t have to be the case.

Contrarian Closing: Why we like first-time CEO’s

With respect to all of the points above, we beg to differ. When it comes to early-stage SaaS businesses, we dig first-time CEO’s. While there are many undeniable benefits of prior CEO experience, there is also a lot to like about first-time CEO’s in this environment. First, they tend to be quite energized by the opportunity to “make something their own.” This typically translates into a high “want-to” factor, the importance of which simply can’t be overstated (as outlined here). This is particularly true when a leader marries that enthusiasm with a high-level of capacity / competence, which is overwhelmingly characteristic of anyone who is a legitimate CEO candidate. As another short aside, this point reminds me of this gem from Simon Sinek…so, so true). First-timers also tend to have a healthy respect for the complexity of the role / situation into which they are stepping. This encourages them to be open-minded and coachable; and it discourages them from prescribing before diagnosing. This is a crucial point; some of the biggest mistakes leaders make can result from defaulting to the assumption that they’ve already “seen this movie” (aka: fully understand a situation, before having completed exhaustive discovery). Rookies, on the other hand, rarely fall into this trap. Finally, sub-scale SaaS businesses tend to be scrappy and under-resourced; and first-time CEO’s can easily jump-in with both feet. Specifically, they are in a great position to leverage up-to-date expertise that draws on their functional background…and, in the process, to help the business punch well above its weight.

In fairness, not all departmental / functional leaders can successfully make the leap to CEO. We prioritize candidates with high-levels of humility / coachability, EQ (emotional quotient), systems-thinking, and prioritization skills; and the odds of their success are greatly improved by supporting them in an intentional, structured, and consistent way (both of which seem like topics for future posts).

In sum, though, up-and-coming execs can offer a great option as CEO’s of sub-scale SaaS businesses…much more so than is suggested by the narrow paths available for them to get there.

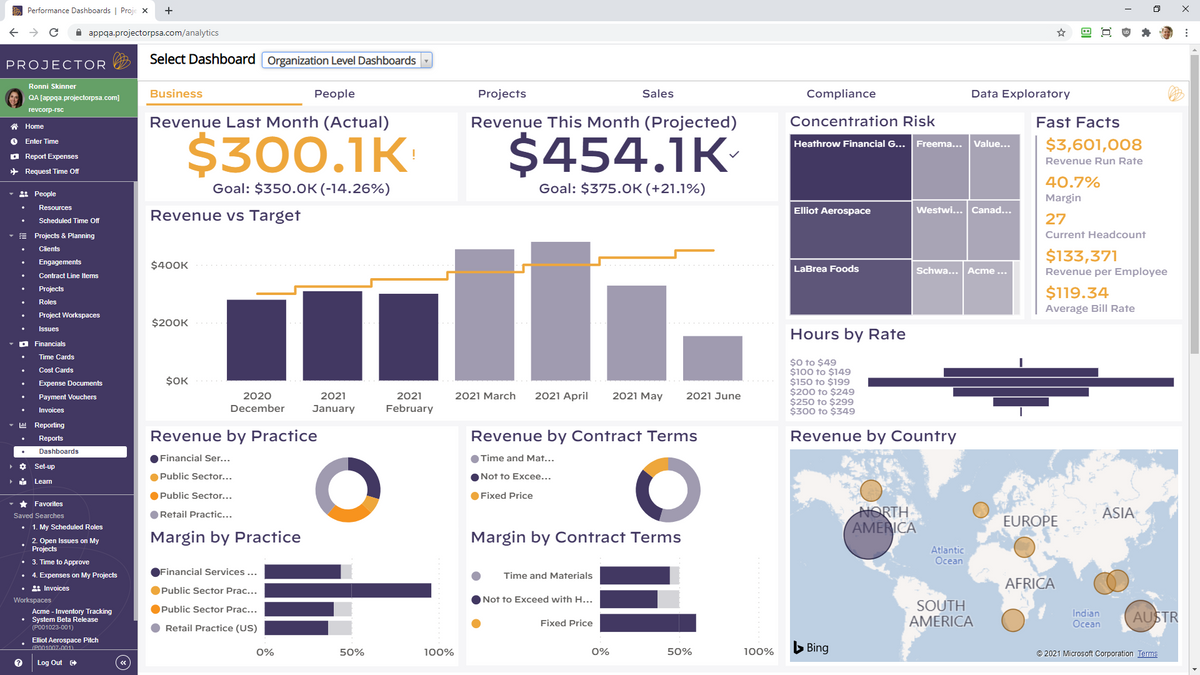

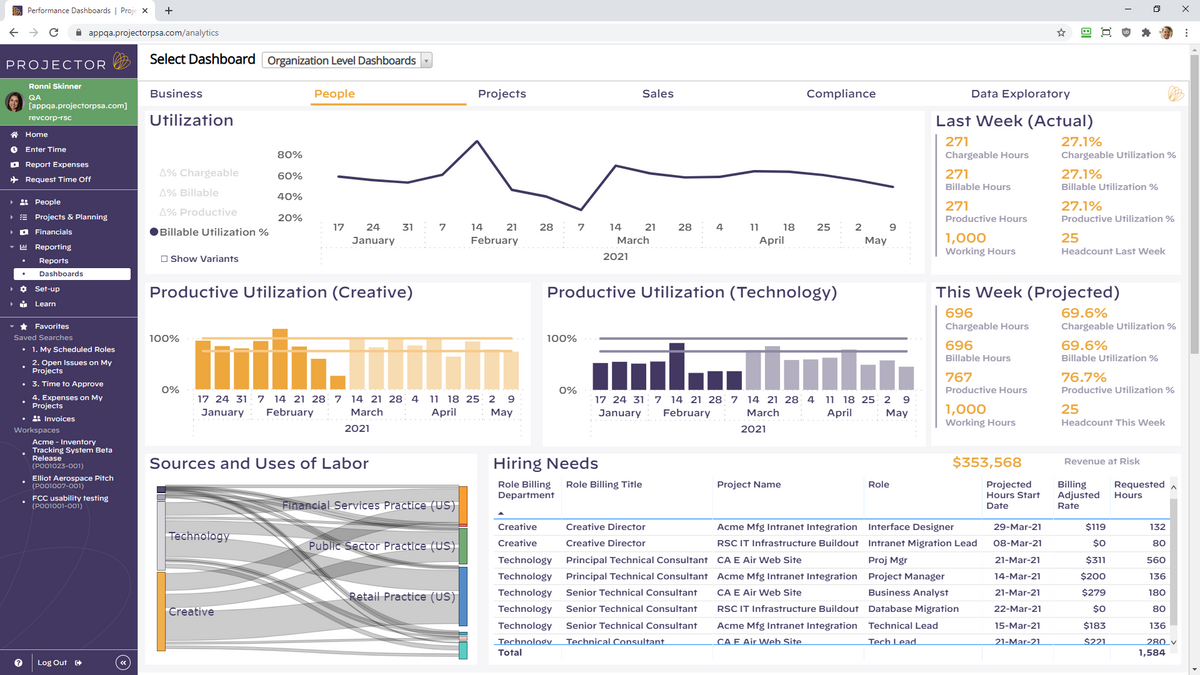

I recently wrote that business dashboards are instruments of control. That observation and the related post, while hopefully helpful, made some general assumptions in discussing dashboards. So, this post takes a crack at addressing an ongoing open point about the existential nature of dashboards: what exactly is their purpose?

Although Stephen Few provides an excellent definition, it leaves room to debate dashboards’ ultimate objective.

Definition: A dashboard is a visual display of the most important information needed to achieve one or more objectives; consolidated and arranged on a single screen so the information can be monitored at a glance. — Stephen Few

Our observation is that the primary purpose of most dashboard initiatives lies somewhere between two general approaches, which can be loosely described as Reporting on one end of a spectrum, and Analytics on the other. The problem many operators face is that their efforts can wind-up betwixt and between the two, often without even realizing it. These two poles offer useful guardrails when considering the objective of any dashboard initiative; and examining and choosing between them helps to clarify many aspects of that dashboard. This kind of clarity, in turn, can help align and ultimately exceed stakeholder expectations.

Five seemingly simple (but deceptively challenging) questions offer a good start toward getting people on the same page:

Although they’re a good start, these questions can admittedly be a bit opaque for practical application. To make them more actionable, we expanded the questions into a “quasi-diagnostic” table. This table captures attributes and examples of each approach, to help leaders identify and intentionally choose how best to prioritize and proceed.

Identifying these characteristics and having open conversations about each can certainly de-mystify the purpose of dashboards and put an organization in a better position to optimize its time and resources.

A few caveats / qualifiers / comments about the above:

In closing, it seems worth following-up with one of my favorite go-to questions: So what? Why does the debate about dashboards’ purpose even matter?! Quite simply, intentionality matters when it comes to metrics measurement. Contrary to popular lore, it’s not so much that “what gets measured gets managed;” Danny Buerkli does a great job debunking that familiar trope here. Rather, as Buerkli succinctly argues, “Not everything that matters can be measured. Not everything that we can measure matters.” So true. And because sub-scale SaaS businesses operate in a world of big dreams but small teams, focus is our friend. Like any other product or service, dashboards should have a clear approach, objective, and target stakeholder…lest they lose their incisiveness and value. So, when considering dashboards, as with all things related to business building — choose wisely and with intent.

I’ll admit that I love a good dashboard. As an aid to SaaS operators seeking to optimize business performance, dashboards can be invaluable.[1] Stephen Few defined a dashboard as, “a visual display of the most important information needed to achieve one or more objectives; consolidated and arranged on a single screen so the information can be monitored at a glance.” This is a useful definition that makes clear: dashboards are instruments of control. Specifically, just as dashboards within vehicles aid in the controlled navigation of those machines, company dashboards help leaders drive organizations forward while controlling speed, direction, and business health. And yet…the irony of dashboards is that before advancing any aspects of a business, sacrifices must first be made in the very same areas that leaders seek to optimize. To go fast, you must first go slow. To go far, start with steps backward. To increase control, make a conscious decision to loosen oversight.

With these contradictions in mind, this post strives to flash a warning light (see what I did there?) by dispelling any illusions leaders may have about scoring easy wins with dashboards. Rather, it introduces some questions to ponder and detours to explore when considering dashboard initiatives. Hopefully these will help folks achieve the goal of getting past the entry-ramps and using dashboards to confidently drive the business forward in the fast lane.

Control: This is What Democracy Looks Like? Advocates of dashboards sometimes tout them as nobly delivering democratization of data. But do dashboards inherently reinforce the notion of one person, one vote? Not necessarily (the term “executive dashboard” seems to succinctly refute this point). Rather, a key question to be answered early in a dashboarding effort centers around data roles, rights, and privileges. Who gets access to what data? Is the dashboard’s audience the CEO? The Leadership Team? Every team member within a business (including / excluding contractors and consultants)? Should there be a curated / filtered set of data for each? Oh, and, what about the board of directors?

A related question centers on how dashboard information is consumed — on a push or pull basis? Purists might argue that dashboard users should be able to “pull” information. That is, they should be able to access what they want, when they want it, and manipulate the information to suit their needs. The problem, of course, is that this is horribly inefficient and variable — we humans rarely know what we want until someone presents it to us as a solution to our needs. That view supports the position of what I call “curators” who believe dashboards are best served up on a push basis. In an extreme version of this model, some analyst-type packages up KPI’s into a report and shares it with a defined set of stakeholders on an agreed-upon cadence. This approach is certainly efficient / prescriptive, but not at all a beacon of data democracy.

My own experience here is that the middle is marvelous. Dashboard information is most valuable when shared broadly with a large number of stakeholders and with minimal access constraints. But the dashboard should also be structured and streamlined, not just a filtered database that can be used to spin-up infinite ad-hoc reports (after all: if everything is important, then nothing is). Finally, regularly scheduled all-hands reviews of the dashboard by company leaders are key to offering commentary and context. This helps provide all stakeholders with a clear understanding of “what matters, how we’re doing in those areas, and what each of us can do about it.” In this way, leaders can absolutely gain more control over their business through dashboards. But they must first be prepared to loosen the reigns on potentially sensitive data and to make themselves vulnerable by sharing it (in good times and bad). I’d argue this approach doesn’t represent a pure (data) democracy, but perhaps it is more like a high-functioning (information) republic.

Speed: Slow is Smooth, and Smooth is Fast: This useful adage from the Navy SEALs has been widely analyzed (e.g. here, here, and here). The general gist is that “the best way to move fast in a professional setting is to take your time, slow down, and do the job right.” This is particularly prescient in connection to implementing business dashboards. As leaders, we want dashboards to serve as an accelerant: to provide early alerts about deviations versus plan, to streamline our decision-making, and to speed the pace of collective results. But…to go fast, we need to start slow. A big-bang approach simply doesn’t work when creating dashboards. Never have I seen a version 1.0 dashboard that was worth a darn. In fact, “if you move too quickly, you bump and bounce and veer from that path because you are frantic, trying to do too many things at once.” Rather, a deliberate and iterative approach to creating dashboards allows leaders to test, learn, adapt, and develop a dashboard that truly serves the needs of the business — over time.

A corollary to leaders’ “need for speed,” is the desire to automate the updating of dashboards. Like a scene from Minority Report, the dashboards in our imaginations should miraculously and effortlessly pipe future-illuminating intelligence directly to our brains on a continuous loop. It’s a compelling vision; and automated updates to dashboards are totally doable — eventually. But a fair degree of manual work is necessary to get a dashboard stood-up. Manual data-entry (the antithesis of tech-enabled efficiency) is often required at the outset of a project, particularly in the early iterations described above. Even after graduating from data-entry, labor is needed to enable efficient and error-free data feeds from different company systems. It. Just. Takes. Time.

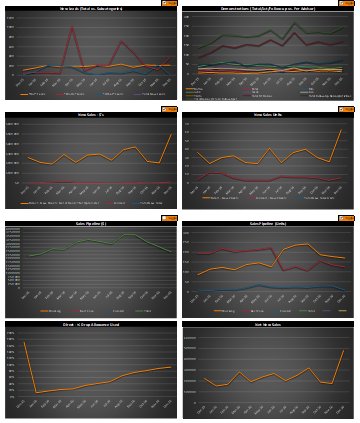

In my view, balance is helpful in navigating the tension between slow and fast. Having botched overly ambitious dashboard initiatives, I’ve learned to start small and slow. It’s wise to avoid throwing out an otherwise valuable metric, simply because it is hard to collect — report what matters to the business, even if it requires manual data entry. Conversely, don’t prioritize the automation of data collection early in a dashboarding effort. Doing so can mean “letting the great be the enemy of the good;” and technical glitches have killed countless promising projects. One of my all-time favorite dashboards (a snippet of which is included below) took 18 months to get right. Initial versions were brutally tedious to update — manually. And even in its prime, it was never visually impressive. But, by taking our time, we eventually created an astonishingly valuable tool that helped accelerate the business.

Horizon: Is Real-Time Really the Best-Time? Another common hope among leaders is for dashboards to help predict the future. This translates into wanting to (a) report the most up-to-date information and (b) measure that information in shorter and shorter chunks of time — by month, week, day, hour, and even by the minute. This works well for many metrics, where recency really matters. For SaaS businesses, such metrics might include website visitors, numbers of qualified leads, product usage metrics, or volumes of support tickets.

But other metrics evolve on a slower cadence; and measuring them over short time horizons is less helpful. As a correlate, I’m reminded of the recommended method for taking one’s pulse: top medical organizations advise counting someone’s pulse over a 60 second span. Although it would be a lot more efficient to measure someone’s pulse for only 2 seconds and then multiply the result by 30…that would give a far less accurate reading. Similarly, many metrics in SaaS businesses require measurement over a longer period, lest the results be useless or misleading. This is particularly true in enterprise businesses selling large dollar subscriptions over long sales cycles. In such cases, one week’s worth of data can have very limited utility; rather, we need to see data over a quarter or even multiple quarters. Examples of these longer-lead metrics include: sales and marketing conversion rates, contracted new bookings performance, measuring execution against hiring plans, or quantifying employee engagement. All of these tend to take a long time to materialize and are inherently “lumpy” in nature.

Where this can lead to dashboard-related trouble is when we try to measure all metrics on a uniform cadence over consistent time horizons. Rather, leaders need to approach dashboard projects with realistic views on just how real-time their measurements should be…and apply time horizons unevenly across different metrics.

To further complicate this issue, today’s results are often best interpreted by looking backward in time. This is challenging for many reasons. First, we often don’t have access to good historical data, which is commonly the motivating factor behind the dashboard project in the first place. Looking backward in this way also contradicts every instinct of the future-focused leader who has undertaken a dashboard project for the stated purpose of more proactively looking ahead. While real-time data is certainly appealing, successful dashboard efforts must also consider both current and past data over long time-horizons.

Conclusion: In sum, dashboards can yield valuable results for businesses and offer great benefits to thoughtful business leaders. Specifically, they can increase the control, speed, and foresight with which the business operates. But none of these benefits comes without a cost. And that price is often paid in the form of leaders first making sacrifices, or investing time and resources, in the very same aspects of the business that they wish to ultimately optimize.

Footnote:

[1] Dashboards are also imperfect and highly variable, as argued well here and here.

As he does in his blog with astonishing frequency, David Cummings last week put his finger on a pervasive problem in startups: complexity of messaging. To cap-off a characteristically well-constructed case for communicating with simplicity, the post concludes with this guidance to operators: “The next time you describe your product, competitive position in the market, or value add, reduce the complexity of the verbiage. Increase the understandability. Make it clear.” Such great advice; and I’ve been thinking about it all week. But, like many things in life, it is easy in theory // difficult in practice. So, I’ve tried here to stand on the shoulders of a giant, and offer 10 tips & tricks that we’ve employed in our own efforts to follow David’s counsel toward clear messaging:

In short: David Cummings was dead-right — in terms of company messaging, make it clear! Hopefully these tips make it a bit easier to do so.

In September of 2020, I attended SaaStr Annual and wrote about it here. It was my first fully virtual multi-day conference; and there was a real novelty factor to it. Seven months and several digital conferences later, I’ll admit to eagerly awaiting the return of in-person industry events. Still, I was pretty fired-up to take part in SaaStr Build this week; and it did not disappoint. The return on my time-invested was high, with a mix of valuable takeaways and follow-up research to do. My hope in this post is to succinctly share some of my personal highlights with anyone interested but unable to attend the event. Specifically, below are 5 content takeaways and 5 general observations, hopefully in under 5 minutes of reading. Ready…go.

CONTENT:

GENERAL REFLECTIONS:

Parting Thought: To make up for having cheated above, I’ll add one last point. I commented in September on the general air of uncertainty at that time and the silver lining at SaaStr Annual of a related (and welcome) vibe of community / humility among attendees. With SaaS multiples at all-time highs, that uncertainty seems to have been replaced with open bullishness at SaaStr Build; and the event certainly offered ample grounds for optimism in the space. My hope for the SaaS community in the coming quarter+ is that we continue to experience sustained market strength…AND / BUT that the same sense of community also endures. Here’s to 2021.

Valuations for publicly traded SaaS businesses are bananas right now. At the time of this post, Zoom’s enterprise value relative to its last twelve months of revenue (EV / LTM) was an eye-popping 58.41x. Veeva’s EV / LTM ratio was 37.02x; and “lowly” Salesforce’s was 10.03x. And it’s not just the stock market; valuations for privately owned SaaS businesses are also flying high. Against this backdrop, a colleague recently shared with me commentary from a similarly frothy time for software businesses. In mid-2011, legendary venture capitalist Bill Gurley tackled the topic of business valuations in his Above the Crowd blog with this article: “All Revenue is Not Created Equal: The Keys to the 10X Revenue Club” (5/24/11).

In this piece, Gurley makes a compelling case against the use of revenue multiples as a means for valuing businesses (“…the crudest valuation tool of them all”). But, seemingly acknowledging the ubiquity and simplicity of revenue multiples relative to his favored Discounted Cash Flow analysis, he then goes on to comprehensively explain the characteristics of high-quality revenue companies versus low-quality revenue companies. These differences, he argues, are what accounts for high valuations (10x+) for some companies, and not for many others. In some ways, the article offers a fun look-back to a seemingly quainter time (e.g. LinkedIn had just gone public that week in 2011, and analysts were skeptically scrutinizing its implied multiple of 11.8x — 15x forward revenues). But it is also a timeless study, with many insights that remain applicable today. With that in mind, below is a quick re-cap of Gurley’s Top 10 business characteristics for gaining entry into the “10x Club,” along with some added thoughts about how these apply today within Lock 8 Partners’ core focus area of small-scale SaaS businesses:

Conclusion:

Managing this 10X Scorecard can seem daunting; many of the components are interdependent. And in small-scale, resource-constrained SaaS business, the tyranny of the urgent can overwhelm even the best laid plans. While year-end brings the customary focus on the planning for the New Year, aligning those plans with your equity value aspirations is good discipline. Because, regardless of whether you’re doing $1M or $10B of revenue — and regardless of whether it is 2011 or 2021 — the characteristics of what makes a quality business remain broadly the same: sticky product, competitive moat, high gross margins, and bankable counterparties are critical for long-term success…and the market will value your business at its discretion.

Tis the season…not for jolliness…but for annual forecasting. Countless companies spend the month of December frantically closing out the current year, while scrambling to codify goals for the fiscal year ahead. So, for many small-scale SaaS businesses, this is decidedly NOT the most wonderful time of the year. Rather, when it comes to financial planning and analysis, it can be a time of feast or famine. Famine in this case is represented by simply not doing any intentional planning. A surprising number of small software companies don’t share fiscal goals with their teams, or even set formalized financial plans whatsoever. Feasting, in this case, occurs when a leader’s eyes are bigger than their mouth, resulting in an unreasonably aggressive growth plan based on exuberant hope more than rational thought. Perhaps this is less like feasting, and more like binge-eating junk-food (in that it is based on impulse, offers a temporary jolt, induces sickness soon after, and is terrible health-wise in the long-term). But neither of these extremes is necessary; and a thoughtful plan does not require gobs of bureaucratic process (one of the primary excuses offered for this feast / famine dynamic). Rather, we’ve seen that the simple concept of triangulation can efficiently produce the building blocks of an informed financial plan that balances multiple perspectives on the business. Here’s how it works:

First thing first, this approach focuses overwhelmingly on setting the top-line goals for a business. The long-pole in the financial planning tent is this top-line goal (also known variously as: revenue, bookings, ARR, and sales). This is because sales performance ultimately dictates the money flowing into the business and highly influences the expense levels the business can sustain. Note: admittedly this is more nuanced in businesses with outside funding, but eventually holds true as they mature toward cash-flow breakeven. Bookings are also the most highly variable / least-controllable aspect of any plan, as discussed in this prior post; and getting the top-line goal wrong can unleash a cascade of pain throughout the entire business. For these reasons, setting an appropriate top-line goal is the critical step in developing a sound plan. The reality is, that this goal must be ambitious enough to please financial stakeholders, realistic enough for the team to execute with confidence, and based credibly on relevant historical data (while also not being shackled to the past). A tall order, indeed.

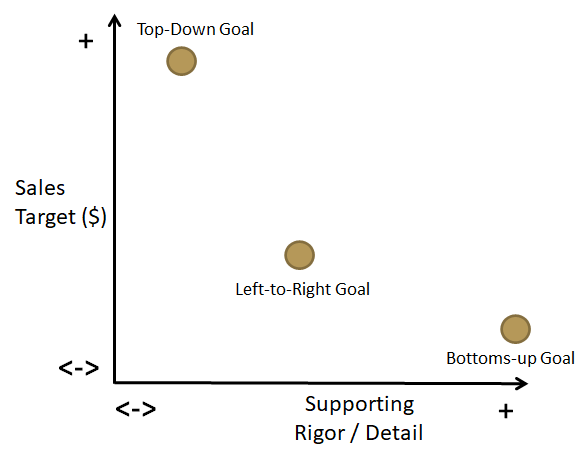

To ultimately arrive at an appropriate goal, we like to start by pulling together three different top-line targets based on three distinct views into the business. Later we’ll compare / contrast / compromise across the three resulting targets, hence the term triangulation. The three perspectives in play are (1) top-down, (2) left-to-right, and (3) bottoms-up, as follows:

Generally speaking, Left-to-Right tends to be the middle-child in our family of goals — neither the aggressive hyper-achiever, nor the black-sheep slacker — just…meh. (Note: this last statement comes from a card-carrying middle-child).

Bottoms-Up: This approach constructs a bookings goal from the bottom up and represents the perspective of the person / people responsible for driving day-to-day sales results (e.g. CRO, VP of Sales, VP of Marketing). This perspective starts from $0 on day 1 of a fiscal year and assumes “nothing happens until someone sells something.” More mechanically, it establishes a bookings forecast from its component parts by building up a notional population of representative sales deals across a time-period. This approach tends to incorporate multiple inputs into detailed models, including:

The resulting forecast from such an approach tends to be quite conservative, sometimes prompting accusations of sandbagging by its advocates. Almost without fail, this will be the lowest among our trio of prospective top-line targets.

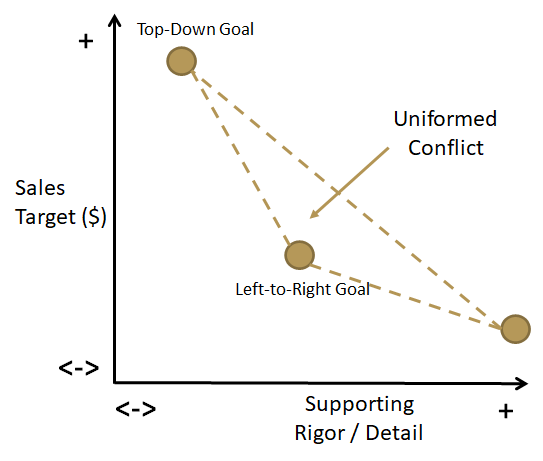

Triangulating: Simply quantifying each of these different perspectives is certainly a step toward a more inclusive and informed top-line goal. But a bit more work at this point is what yields the real progress. The truth is that the three different methodologies produce widely divergent results, both in terms of target figures and the rigor used to arrive at them, so compromise is necessary. Graphically, these could be plotted like this.

Each goal has its own shortcomings, and none of these goals tends to unilaterally offer an ideal bookings target. Without further discussion, these different data points simply shine a light on the misalignment that commonly exists across the various stakeholders. This can look like this:

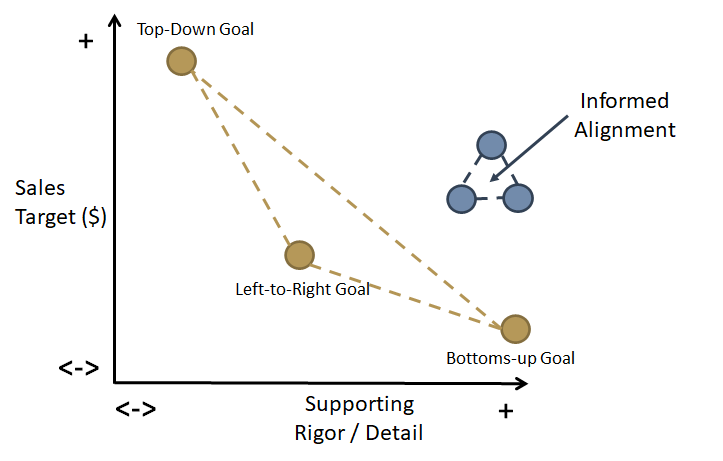

But these inputs also provide the forum for an interactive discussion around the drivers of each. Optimally, organizations can move beyond this zone of Uninformed Conflict simply by asking pointed questions of each goal:

This exercise forces people out of their default perspectives and drives productive (albeit, often uncomfortable) discussions. Inevitably, this drives more informed goal-setting and better alignment across the business…and quite frequently, it helps move the top-line goal up and to the right in our now-familiar graph:

Conclusion: The top-line goal is critical to annual planning efforts. To be fit for purpose, it must balance ambition, credibility, and executability. Only by clearing this bar will it fully serve its multifaceted purpose: to please optimistic financial stakeholders, satisfy the inherent skepticism of internal number-crunchers, and pass the “red-face test” among the troops. Admittedly, this is only a start; and many other components are needed to really nail annual planning. But getting this goal right is a great foundation around which to build; and triangulating across these multiple perspectives is a simple way to inform this process. Plus, doing so is a good way to make the New Year something really worthy of celebration by all stakeholders.