As I’ve written previously, I’m not a fan of the term “playbook,” despite it being a metaphor that is used with reverence in many private equity circles. In my view, the reality facing small-scale SaaS businesses is too complex for 1-size-fits-all playbooks to be universally valuable. But I have also observed that a set of core disciplines consistently catalyzes the sustainable growth of capital-efficient SaaS businesses; and we regularly leverage several frameworks to reinforce these concepts. I was recently made aware that my enthusiasm for such frameworks or mental models had turned me into the proverbial “hammer,” to which everything looks like a “nail.” At the time, I was in a discussion with one of our portfolio company CEOs about a particularly thorny issue they were facing. As I unhelpfully tried to solve the issue with 2x2 matrices, “pattern recognition” drawn from other businesses, and a wealth of publicly available SaaS benchmarks, the business leader kindly said to me, “Hey…you know…not everything is a F8*%^&! framework.” Boom — direct hit.

This simple reminder got me thinking about situations in which a framework or mental model (or a playbook(!)) really are NOT helpful to operators of SaaS businesses. I’ve shared a few of these below. My hope in doing so is that it helps leaders of small-scale SaaS businesses to distinguish between the many situations when a pre-established framework / approach can be extremely helpful…versus those critical instances when a totally unscripted response is not only warranted…it is needed.

Hard Things: In his epic work The Hard Thing about Hard Things, Ben Horowitz argues that building a software business reveals countless problems for which there just aren’t any easy answers for leaders. Those include firing friends, poaching competitors, and knowing when to call it quits (among many others). These are very real, very important, very “anti-framework” type problems. Sometimes things are just…hard. In those situations, it’s important for leaders to stay true to their values, safeguard the company’s vision / mission, and…just keep moving forward. Particularly in situations with no seemingly pleasant options, overly analytical mental models rarely help. Instead, they can delay the inevitable and prolong the agony for all involved. Better for leaders to pull their socks up, and just get on with it.

Art & Science: Some aspects of SaaS businesses are clearly more science than art (examples include financial bookkeeping, constructing entrance / exit criteria for sales stages, and collecting statistically valid NPS data from customers). Still, others are a blend of art and science. For example, we can use a carefully researched product framework to help empathize with, and prioritize input from, customers (science). But it’s a far more artful endeavor to incorporate that input into a brand that faithfully captures the essence and a resonant market-promise that we want to non-verbally convey to all stakeholders. Art doesn’t need a framework; art needs to touch-off the right note in people’s System 1 brains. Note of disclosure: We admittedly do use a number of frameworks to assist in a carefully considered re-branding process. But at a certain point, it’s all about the output and not at all about the process imbued through framework-type thinking.

Unique Problems: It’s been written that “there is nothing new under the sun.” And while I won’t debate this point on a fundamental level, there are exceptions in small-scale SaaS businesses. Although there are a finite number of moving parts in SaaS businesses, fact-patterns often arise for companies, where they are facing challenges that present themselves in completely new and unique ways. For these situations, frameworks are relatively helpful; rather creativity is required. I’m reminded of a platform-upgrade and related migration challenge that we experienced at one SaaS business. The SaaS world has seen countless upgrades / migrations, so we looked to past precedent and roadmaps to inform the initiative. But the specific combination of business context / use-case idiosyncrasies / uptime requirements / seasonality of our customers demanded that we establish a completely unprecedented approach to the migration. A mixture of creativity and ruthless pragmatism carried the day; frameworks were unhelpful.

Make to Scrap: Software is all about efficiency, and we SaaS leaders hate re-creating the wheel. With this in mind, we err toward thoughtfully building our products and processes with attention to ensuring scalability and re-usability. But some situations demand speedy action for a pressing moment, with little thought to future needs. This might mean spinning up a (true) MVP, filling an urgent personnel need with outside resources, or addressing a surprise market condition with a one-time targeted offering. In any of these cases, one-time-only action may trump frameworks.

In closing, and to be clear, mental models greatly assist SaaS operators in countless situations. But it’s also important for SaaS leaders to leave room in their brain to recognize those less frequent situations when frameworks are less helpful, possibly even counter-productive. Where fortitude, creativity, speed, and situational decisiveness are what’s needed most…not everything needs to be a F8*%^&! framework.

I’ll admit that I found it hard in the second half of 2022 to clear-off the white-space necessary to write many blog posts. Candidly, I’ve been in an extended slump on this front. When we find ourselves in a rut, it helps to have friends to lend a hand. With that in mind, I’m grateful to have many such friends in the early-stage SaaS community for just such situations. More specifically, I was delighted when James Marshall approached me with an idea for the “Made not Found” blog that leveraged his deep knowledge of analyst firms. The piece below is overwhelmingly the result of James’ experience and expertise, with a small bit of collaboration from me. Thank you, James, for generously sharing; and thanks to all for reading this post and helping the MnF blog get off the schneid early in ‘23.

Since my days of working for Gartner, I’ve learned to brace myself when mentioning B2B analyst firms to leaders of small-scale SaaS businesses. It’s not uncommon for one tech-leader to describe their industry analysts with admiration, and another to accuse theirs of downright corruption or extortion. A common sentiment is that paid research analyst engagements feel beyond our control, more akin to high stakes gambling than a rational, high-ROI growth strategy.

Over countless meetings with analysts, tech-CEOs, and investors, I’ve observed how great analyst-outcomes must be intentionally crafted by (and for) tech companies. Similarly, I’ve seen how analyst-related failures were quite predictable based on the actions taken (or not taken) by tech companies early-on in their engagements with analyst firms.

Let’s explore three common pitfalls to avoid, key questions to ask, and corrective actions to take. When thoughtfully navigated, these common stumbling blocks can become stepping stones, and serve as a strong foundation for meaningful analyst outcomes.

Pitfall #1: You invested money with analysts who don’t advise your target-market.

Too often, companies pay analyst-firms before confirming how those analysts plan to cover their space in the SaaS universe. This is a costly mistake that results in wasted dollars and time spent with analysts who don’t actively advise your target-buyers.

Key Question to Ask: Do these industry-analysts advise your target-buyers on how to buy solutions like yours? This is an especially critical point for vertical or niche SaaS businesses to confirm.

Key Action to Take: Analyst Interview — Just like you would interview someone for a position in your company, it’s important to take the time to properly interview any prospective key analyst. Discuss the below questions (and do so before any money changes hands!):

· How many conversations a month do you have with our target buyers?

· What is the most common business profile of these target-buyers you advise (revenue, employee count, industry, etc.)?

· What kinds of questions do our target-buyers ask you?

· What challenges are these buyers facing when choosing a solution?

· What kind of research do you plan to write this year? How will it help these buyers?

· Who are the biggest players in this space that my company competes with?

· Do you plan to rank vendors in this space? If so, what criteria will inform your decisions?

Questions like these are the beginnings of a high-leverage analyst engagement. From here, a well-executed engagement strategy will prove more attainable. Conversely, choosing an analyst based on brand awareness (or any other less informed criterion) commonly and predictably leads to dissatisfaction with one’s analyst.

Pitfall #2: You don’t have a strategy for turning analyst-investment into revenue growth.

While an unaimed arrow never misses, it’s best to approach analysts intentionally. This is especially true in the early days of working with an analyst.

Key Question to Ask: What steps can we take to convert the analyst’s influence into our firm’s revenue growth? This can also be a good question to directly and candidly ask the analyst (while acknowledging it is exclusively our job, not theirs, to drive our revenue growth). However, don’t be discouraged if they avoid specific talk of outputs (such as research mentions or referred business). Analysts closely guard their reputation of objectivity, so they generally won’t “go there” in terms of discussing tangible results…but achieving such outcomes remains possible.

Key Action to Take (#1): Identify Strategic Goals — Begin by internally outlining your 12-month goals for the relationship. There are three revenue-generating outcomes in analyst relations:

· Research Mentions: When your company is named in published research, your solutions get shortlisted more often. Your sales team can also leverage this research for instant credibility.

· Referred Business: During a direct conversation with your sales prospect, an analyst recommends that the prospect evaluate your company’s product.

· Insight that enhances your competitive position: This is the most overlooked benefit. As I’ll explain below, analyst-advice is directly correlated to the probability of being named in research or recommended for a shortlist.

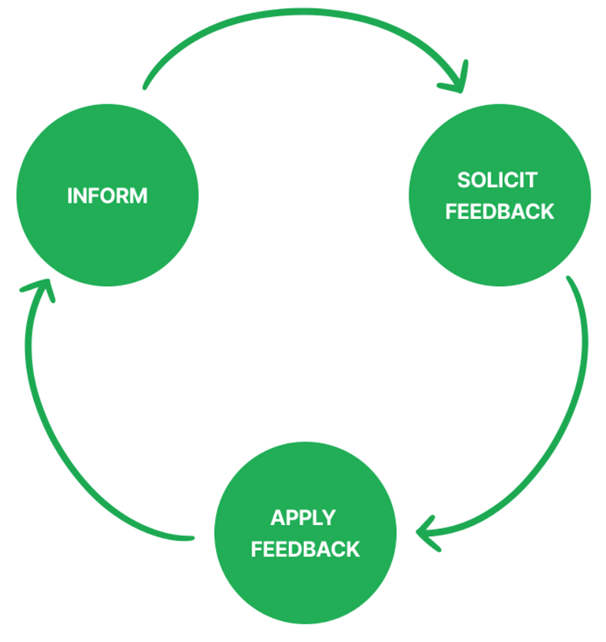

Key Action to Take (#2): Inform, Solicit Feedback, Apply — Here’s the secret: Nobody calls their own baby ugly; not even analysts. Leverage this human tendency by making analysts feel heard in some of your company’s critical decisions.

To illustrate this point, analyst-success can be distilled to the below cycle: inform the analyst about your product, solicit feedback, apply that feedback (if agreeable to your own vision), repeat.

Example: Ask the analyst to prioritize your feature-roadmap based on needs they see in the marketplace. This will be a valuable point-of-view that captures an influential analyst’s mindshare while helping to create an emotional investment in your company’s success. Their output could also save your company countless hours of internal debate!

Real-World Outcomes: The answer to your target-buyer’s question of “Who should we shortlist?” can be found among the vendors who ask that same analyst, “What features do you think are most important for our customers?” Analysts will shortlist vendors who align with their view of the marketplace. The same rule applies for tech companies hoping for favorable research coverage.

Pitfall #3: You’ve assigned the wrong people to speak with the analysts.

It’s common for tech leaders to invest significant capital with analysts, only to assign a lead-gen focused marketer to speak on behalf of their company. Those two parties can’t typically hold a meaningful conversation about your company’s strategy. Analysts catch on to this lack of investment in the relationship by leadership, and the impact to your brand is negative.

Key Question to Ask: Who in our company has the optimal blend of (1) seniority, (2) product / market vision, and (3) time to invest in relationship-building with the analyst?

Key Action to Take (#1): Put leaders in the meeting — The best people to speak with the analysts are the people with the blend of these three attributes; and those tend to be the CEO, the Head of Product, and the Head of Marketing (if they are responsible for packaging, pricing, and messaging…not just lead gen). Up until Salesforce surpassed $250m in annual revenue, Mark Benioff was well known at Gartner for his raucous debates with analysts. He even hired the analyst with whom he disagreed the most!

Key Action to Take (#2): Assign a separate show-runner — While tech leaders should be able to allocate the time to engaging substantively with analysts, they rarely have the bandwidth to establish, manage, and execute their company’s analyst strategy. Be disciplined about assigning someone to run the overall strategy of your analyst engagement, while surgically inserting the right leaders in the actual analyst meetings. This teamwork results in maximum impact. You can assign this strategy to someone internally or to an outside firm (just be careful to find one with real analyst experience, not a generic PR firm).

Conclusion: The Payoff — Intentional engagement with analysts creates significant momentum for businesses. That benefit is felt 10x for startups, where an analyst’s 3rd-party validation provides a level of credibility usually reserved for much larger companies.

For this reason, some tech-focused PE and VC firms spend millions of dollars each year with analyst firms. These investors mandate a well-executed Gartner and Forrester strategy as part of their value-creation playbook. Much the same, some SaaS founders and leaders are savvy analyst-relations pros who execute their own version of these strategies.

These leaders are in the minority and their analyst growth strategies are far from being a commodity. By taking the right steps to pair your company leaders with the right analysts, you can create an analyst-strategy that is a real accelerator to your company’s growth.

A recent post on this blog identified different types of client feedback groups that small-scale B2B SaaS businesses can set-up to intentionally solicit input about their market and solutions. That post went on to assert that managing such groups can be difficult and costly in terms of time, resources, and money. In retrospect, that was probably only partially helpful. This piece aims to improve and expand upon the last one by offering (a) a case for why programmatic client engagement is well worth the investment and (b) a few tips for avoiding some of the (many) mistakes that we’ve made on this front over the years.

It’s Expensive // Is it Worth It?

Yes, it really is. There are countless ways that such groups can benefit SaaS businesses; we’ve coalesced around 5 big ones that we hope to get out of such initiatives.

Avoiding the Pitfalls:

Hopefully the case is clear for why client engagement groups are well worth the effort. So, now for a few words to the wise in terms of do’s and don’ts for managing them:

Hopefully this follow-up post offers a valuable expansion upon its predecessor. In sum, investing in customer engagement is well worth the effort. But, as in all things, a bit of forethought and awareness of pitfalls should make that endeavor more rewarding with less risk.

One-size-fits-all seems to work fine for a few things. These arguably include: plastic rain ponchos, ping-pong paddles, the Flexfit ball caps that my dad likes to wear, and those awful grippy-socks handed out on trans-oceanic flights. For everything else, though, one-size-fits-all is brutal — always sub-optimal, often ineffective, and sometimes flat-out painful.

This principle holds true in many aspects of the small-scale SaaS world. And yet, we SaaS leaders consistently fall into the one-size-fits-all trap when it comes to customer engagement and setting up a formalized channel for soliciting actionable client feedback. There are many reasons for this including the fact that early-stage SaaS businesses often entirely lack an intentional approach to collecting market feedback; and launching an inaugural customer advisory board (often referred to by such acronyms as CAB, PAB, SAB, PUG, BUG, etc.) legitimately represents a major leap forward. Really, it does. Still, a one-size-fits-all approach to customer engagement can sometimes create as many problems as it solves. To describe and to combat that, this post draws on observations across many years & multiple companies to offer a framework for thoughtfully selecting an approach to customer engagement that best suits a business’ specific needs.

First, let’s introduce a few terms that will be useful to any discussion about programs for soliciting customer feedback:

· Focus groups / 1-on-1 Interviews: When conducting a focus group, researchers gather a group of clients / customers / users together to discuss a specific topic (or they do it on a 1-on-1 basis). Usually, the goal is to learn people’s opinions about a product or service, not to test how they use it. On this point, let’s draw a distinction here:

· Surveys: Standardized data collection from clients / users on a defined market or particular product.

· Tools / Data: Methods for gathering broader insights, including product usage stats, industry data, heat maps, A/B testing, etc.

· Client Groups: Convening knowledgeable clients who provide insight on the market and feedback about your solutions via the methods described above.

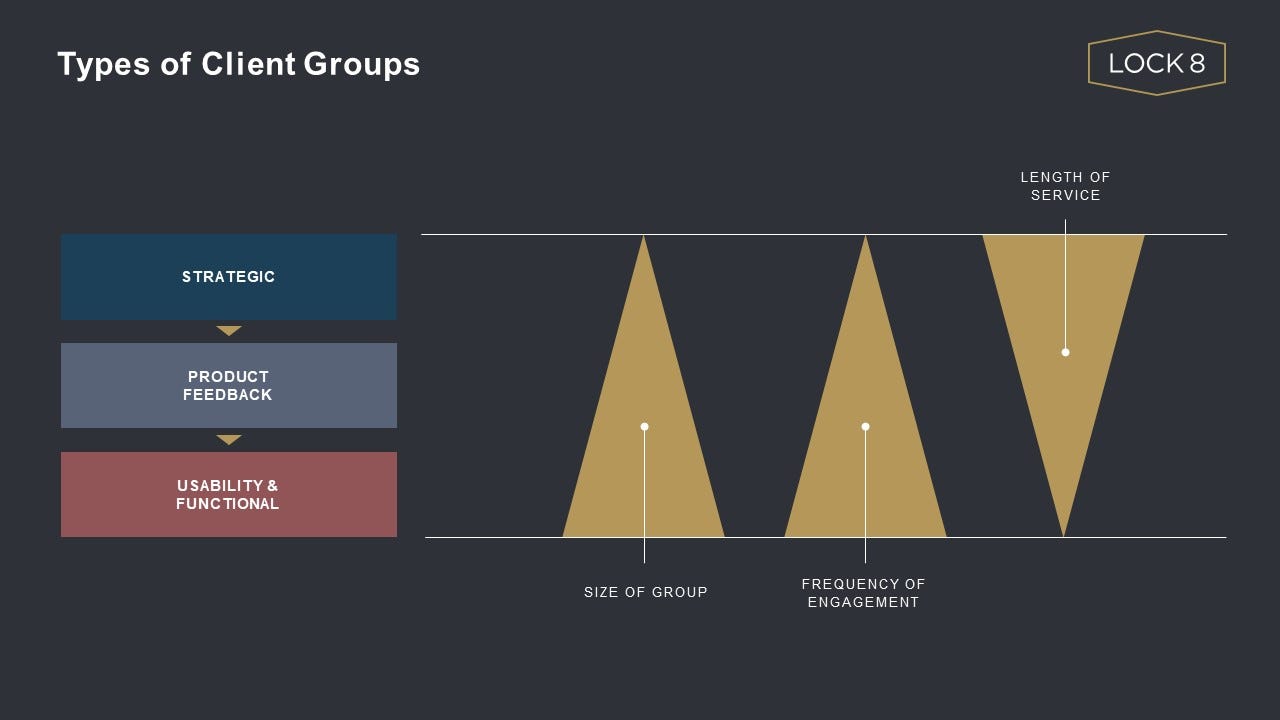

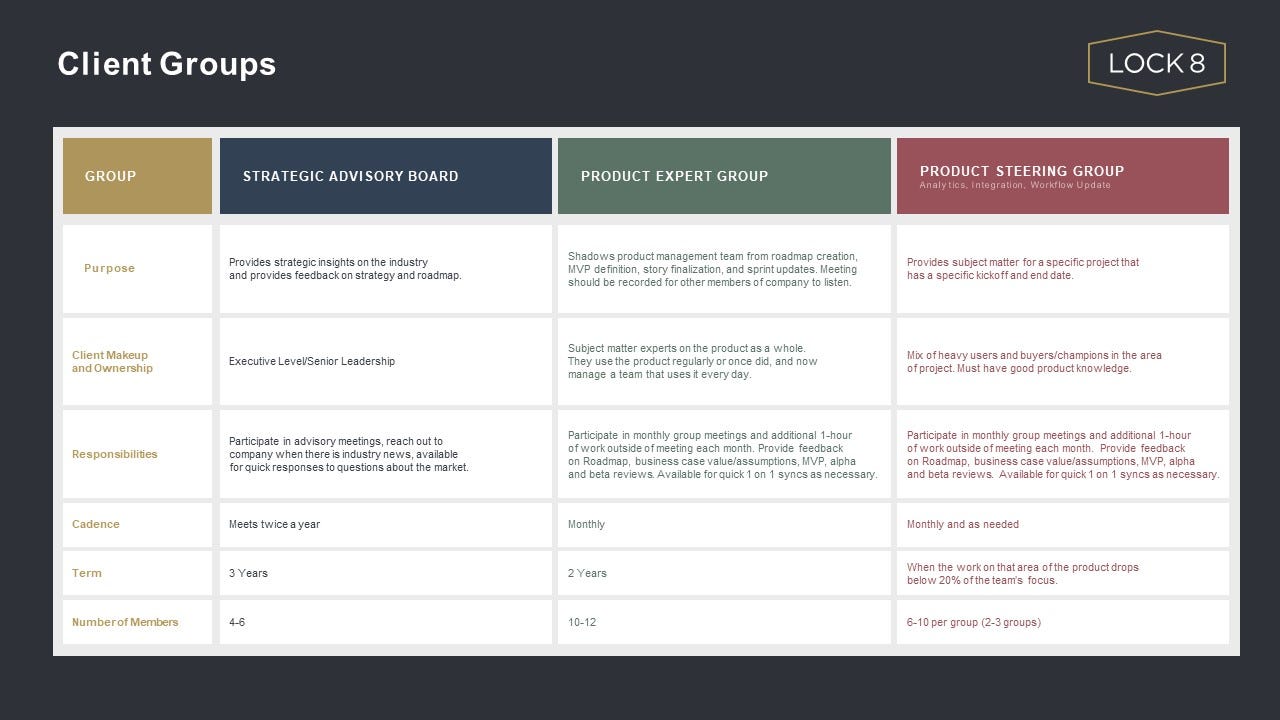

To be clear, all of these can be valuable, but this post focuses on the last of these forms of engagement — client groups. While there are arguably countless different flavors of client groups, we’ve observed three general types, as follows:

Hopefully these brief descriptions make a clear case for how each of these groups would serve vastly different purposes on behalf of a business. The graphic below double-clicks further into how these groups typically differ in terms of size, meeting frequency, and longevity of commitment.

To summarize:

The table below adds some quantifiable detail around how we tend to think about and structure programs for each of these types of groups.

To go one step further, and for those so inclined, it is also worth expanding upon this table as your programs become more formalized. We tend to add the following rows to nail-down additional criteria, including:

In closing, a few words about why these distinctions actually matter: Most importantly, small-scale SaaS businesses have a finite set of resources; and engaging with these groups is hard(!). We think about the challenges of managing user groups in two categories, as follows:

I. Time & Resources — it takes a lot of both; below is a set of related tasks:

II. Mixed Results — the hard reality is that these forums don’t always yield the expected outputs; below is just a small sampling of ways these groups can run off the rails:

As a SaaS business evolves its programs for engaging with customers, it would be ideal to simultaneously manage a portfolio with one (or more) of each of these user groups. Sadly, (to repeat) small-scale SaaS businesses constantly balance the tension between an infinite set of possibilities against tightly constrained resources. Given that, it’s important that they ruthlessly prioritize in all areas, including how to programmatically solicit strategic / product feedback from their clients. So…with many small-scale SaaS businesses looking first to mature to the point of having even just ONE of the customer feedback groups described above, it’s important to do so with intentionality. Because, as with most things, one size does NOT fit all…avoid the plastic poncho; and choose wisely.

A word of thanks to Paul Miller, ardent product management leader, now CEO, and previous thought partner to this blog, who recently helped me to crystallize “what good looks like” in terms of customer engagement programs.

3

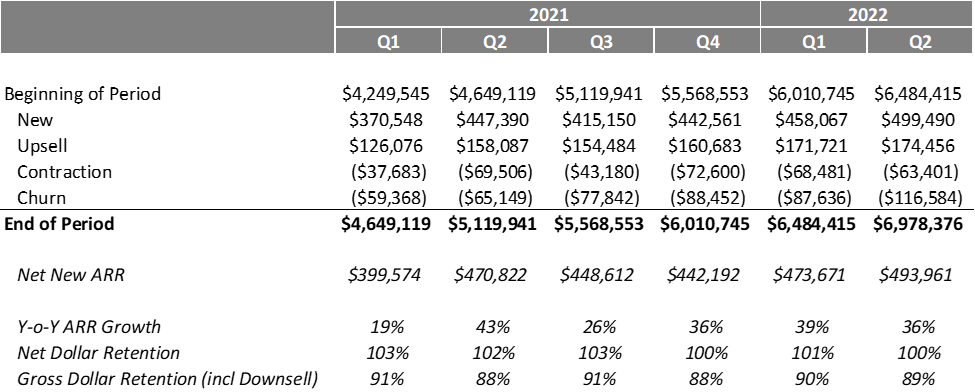

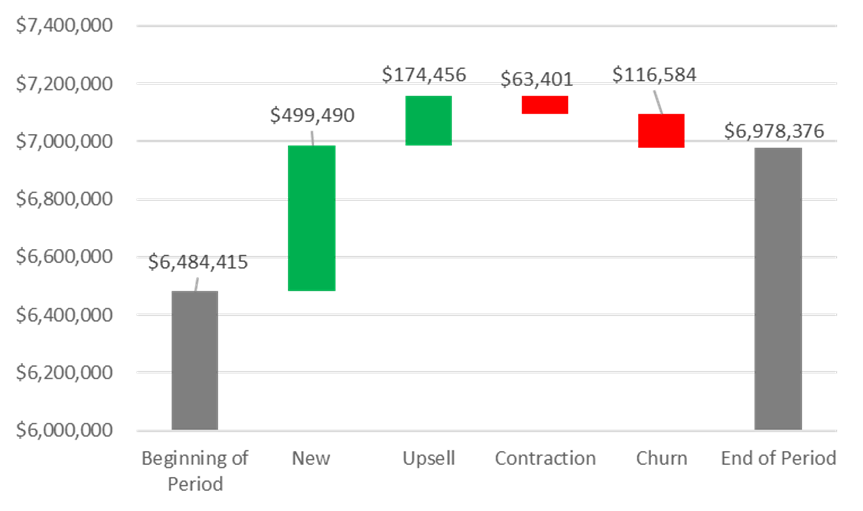

Over the past decade, the “ARR waterfall” or “SaaS revenue waterfall” has become a mainstay within the landscape of SaaS metrics and reporting. This is hardly surprising: operators, investors, and analysts all need a commonly accepted standard for assessing the topline performance of SaaS businesses; and the ARR Waterfall conveys so much in only a few lines (for this reason, I’d submit that the ARR waterfall is essentially the haiku of SaaS reporting…but I digress). As in the example below, an ARR waterfall neatly ties together new bookings, upsell, contraction, and churn into a structured, easily digestible story around the surprisingly complex question of how much net Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) a business adds in each period.

We also like a purely graphical / summary representation of this table, which is likely the source of the term “waterfall:”

This all works well in a prototypically tidy SaaS business: clients pay a specified amount for subscriptions to use a SaaS solution over a designated period, renewing that commitment at regular intervals. These renewals typically take place on an annual or monthly basis (or do NOT take place, resulting in “churn” or “drops”). Likewise, this quintessential SaaS business tends to offer graduated packages (“Good / Better / Best”) of its solution and/or allows customers to add or remove modules on top of a base subscription (“Core + More”). These add-ons lead to ARR expansion (aka “upsell”) but can also result in contraction when customers elect to scale back their licensed capabilities (aka “downsell”). In this scenario, new bookings, upsell, contraction, and churn all tend to be discrete, knowable, and quantifiable figures…in other words, comfortingly black-and-white.

The dirty secret within many SaaS businesses, however, is that the world is a lot messier and more complicated than ARR waterfalls would make it appear. Below are just a few examples of common nuances, along with the inevitable Good, Bad, and Ugly that each represents to SaaS providers trying to craft a tidy ARR waterfall — and, finally, some closing thoughts around how to manage such messiness:

· What if your business offers usage-based pricing, whereby clients get billed based on an amount of actual usage over a given period? Note: usage can be measured in countless ways (number of users, volume of transactions processed, database calls executed, and others).

· What if a benefit of your SaaS offering is the ability for clients to terminate contracts at their convenience and/or that these are evergreen contracts with no set renewal date?

· What if there is a mix of pure subscriptions (where clients manage their use of the software) along with technology-enabled reoccurring managed services (where the vendor provides admin and management of the solution on customers’ behalf)?

Before going any further, I’d offer that these situations are surprisingly common in the SaaS world. Many SaaS businesses, particularly those that Lock 8 invests in, offer such contractual nuances that go against traditional commonly accepted SaaS “best practices.” Although SaaS purists tend to poo-poo anything less than straight subscription revenue, customers often appreciate and ascribe value to these nuances (as Jason Lemkin wrote compellingly about here); and smart companies make the conscious decision to manage the tradeoffs described above. Some of the best companies we’ve worked with do exactly that. But…there is a catch. If your revenue model deviates from pure subscriptions, then it’s important to take steps to manage and monitor ARR reporting with great intentionality, as follows:

Now for the big finish to this post, please queue audio from TLC’s classic, and former Billboard #1 hit, “Waterfalls.” Per TLC’s timeless wisdom: “Don’t go chasing waterfalls”…instead, carefully Define, Align / Refine, Baseline, and Trend Line your own.

Pronouns have been a hot topic for some time (as evident here, here, here, and here). The use of pronouns is an important issue with serious social implications. However, those are not the focus of this post. Rather, this piece more narrowly tackles pronouns in connection to a separate but related topic: the language of leadership. It may seem like a leap, but please bear with me here:

In his amazing work, Language and the Pursuit of Leadership Excellence, Chalmers Brothers makes the case that leaders get paid to have effective conversations. In this TedTalk, he goes on to explain: “Leaders create and continually sustain and cultivate this non-physical, but very real and very powerful thing called corporate culture. Not with tools and fertilizer, of course, but with the conversations they have, the conversations they require, and the conversations they prohibit.” Totally agree…as touched on here in a prior post on this blog. An important part of such conversations revolves around how leaders address or reference themselves and others; and a critical linguistic device for doing so is this thing called a pronoun. Although pronouns tend to be short / small words, they can have an outsized impact on relationships; and this post offers some observations around how pronouns can either support or undermine leaders’ efforts to build culture and deliver results.

Let’s first cover third-person pronouns (he / she / it / they, and related derivatives), since these are the ones that have received by far the most popular attention in recent years. That notwithstanding, third person pronouns are actually NOT the main focus of this post, save for one very important point: effective leaders will take pains to refer to people how they want to be referred. Period. Although this seems like a basic gesture of human respect, it gets botched and not just via presumptive use of traditional pronouns. When multiple teammates share a common name, leaders sometimes innocently call one or many of them by different versions of that name. For this very reason, my father “Rob” was known (annoyingly for him) throughout his entire career as “Bob.” As is the case with an unwelcome pronoun, being called by a name that you don’t like inevitably leads to at least some loss of identity — and lower performance. For this same reason, nicknames in the workplace can be problematic. At one firm early in my career, the name Todd somehow evolved into the nickname “Toddler,” which is how virtually everyone referred to me. I hated it; and it was a contributing factor to my feeling disconnected and disenfranchised at that business. Countless examples abound, and thoughtful leaders work hard to conscientiously refer to people either directly or via third-person pronouns based entirely on their stated preference.

Less obvious to the language of leaders, but arguably even more important, are first-person pronouns (I / we, and derivatives of those). The old saying goes: “There is no ‘I’ in team.” I suppose that is partly true, but with some nuances. Certainly, leaders should avoid taking personal credit for the accomplishments of their organizations. Founders / leaders can create “nails on a chalk-board” moments when they assert things like: “I did $4M in ARR last year,” or “I’m going to deliver ground-breaking new product capabilities in this next sprint.” There is no surer way than appropriating a group’s collective efforts for ego-centric leaders to turn-off their hard-working, under-acknowledged colleagues. Actually, very few stakeholders react well to this habit; we all seem to innately understand the African proverb, “If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together.”

Conversely, the use of the first-person plural pronoun “we” is almost universally appropriate in leadership moments and settings. The term “we” inclusively shares credit and collectively establishes accountability. When in doubt, leaders should consistently default to the term “we” for virtually all stakeholders. This extends beyond a leader’s core team to include customers, prospects, investors, and even competitors. “We” opens a ton of doors, possibilities, and goodwill.

Now…having said all that, strong leaders understand that there actually should be at least one “I” in team — when things go wrong for the organization. When this happens, leaders use the first person singular, as follows:

For effective leaders, there really is an “I” in team…it gets spotlighted when modeling good behavior around embracing vulnerability, adopting a growth mindset, and establishing an environment of accountability…and in encouraging others to do the same.

Finally, the trickiest pronoun of all — second-person (you / you guys / y’all / yinz (when in Pittsburgh), and similar derivatives). When addressing a group, leaders should generally avoid using the word “you,” pretty much…ever. It creates separation from the speaker in a way that is rarely helpful. This is particularly true in a leader’s first 90 days, where using the collective “you” can quickly alienate one’s new team. This may seem innocent enough (“You did this differently in the past than how we’ll approach it going forward.”). But what audiences tend to hear is their leader creating factions within the organization, judging the old-guard, and not yet taking full ownership for the organization as it exists today. This simple slip can sink a new leader before they even get under sail. Even for longer-tenured leaders, I’d contest that the potential costs of using “you” almost always outweigh the benefits. For example:

None of these statements fosters a shared sense of purpose, instead creating an adversarial dynamic. Admittedly, all of the above examples have negative context. Surely “you” can be used in a positive context, such as when praising someone for achieving great results. Right?! I mean…sure, but I’d actually advise against it. Telling someone, “You did a great job,” may sound good on the surface, but it often can be somewhat exclusionary. Specifically, singling out a person (or group of people) runs the risk of undervaluing the countless interdependencies and unseen contributors that are required to achieve any shared goal. This occurred just this week at one of our portfolio companies, in the wake of a successful bookings quarter. One well-meaning exec said to the head of Sales, “Thank you to your team for hitting our bookings number!” Understandably, the head of Marketing, feeling slighted, fumed on the other side of the room. Thankfully, the Sales exec had the good instincts to gracefully point out that it was a team effort across all functions. To emphasize this point, he offered: “Really it’s thanks to all of us; yay for us as a whole…we were only able to beat plan by working together.” Boom! That was an elegant and effective substitution of “we” for “you.”

In closing, like most things, guidelines for the use of pronouns should be followed with a balance of discipline and pragmatism. A bit of attentiveness can go a long way toward avoiding the most egregious or recurring infractions. On the other hand, maniacal adherence to these points can tie leaders in verbal knots, ironically reducing the authenticity and effectiveness of their communications. Leaders should be themselves…and maintain big ambitions for their conversations…but also keep a close eye on those little words, because they / we / you really matter.

A prior post on this blog referenced the use of formal assessments as a vehicle to support first time CEOs. I have admittedly received pushback in the past on this point from experienced CEO-pals who question the value of such instruments. Fair enough; to each their own. But I stand by that position and offer this post in an effort to support it. This piece will double-click into three questions relating Lock 8 Partners’ use of diagnostic tools for execs:

I. What is the general thinking behind using formal appraisals with execs?

II. Which specific tests do we use and why?

III. How do we administer and use the assessments for optimal impact?

The goal here is to share some lessons learned in order to help others optimally position CEOs / execs for success in their leadership roles.

I. General Thinking:

Leadership is critical to organizational performance, and CEOs / execs are key drivers of company success. Likewise, CEO roles — even in small businesses — are enormously complex, with many potential variables ultimately influencing outcomes. At Lock 8, we naturally want to leverage any available resource to help CEOs succeed, particularly the first-time CEOs whom we prioritize hiring.

To be clear, our objective with these assessments is not to weed out the “smart” from the “astonishingly smart” — that’s not what we believe matters most to small-scale SaaS businesses. Rather, we are trying to understand how execs align to a specific role in two main areas: (1) personality factors and (2) problem solving. To do this, it is first necessary to have an in-depth understanding of the particular business and nuances of that particular executive role. Only with that context are we then able to use these two types of information to understand how someone aligns to a given role, builds relationships, performs under pressure, processes information, and makes sound decisions. If an assessment can offer an advantage to our CEOs in this fascinating and high-stakes puzzle, then sign us up for these tests…

II. Which Test(s):

…but, not just any test, and certainly never only one test. The CEO role and the individuals who successfully navigate those roles are simply too complex to rely on any one measure to predict success. It would be the equivalent of saying “choose one thing that makes all CEOs successful” — it just doesn’t exist. Rather, such a multi-faceted endeavor warrants using several different tools, measures, and techniques. Following expert guidance, we have oriented around four tests, with two focused on each of (1) personality factors and (2) problem solving.

Personality Factors: Personality factors speak to the types of preferences and inclinations that determine how a person is likely to behave under normal circumstances, as well as when under pressure. We use two instruments to measure these different aspects of personality; they are the Hogan Personality Inventory (HPI) and the Hogan Development Survey (HDS).

The HPI is a measure of “normal personality” that provides the following:

The HDS identifies the following:

The HPI and HDS provide a more in-depth understanding of the preferences and thinking that drives what many refer to as “Emotional Intelligence” (EI) or “Emotional Quotient” (EQ). They also facilitate a very quick / early understanding of an exec’s communication style, in order to better inform how that person could interact with a team. Research consistently shows that leaders who have higher self-awareness regarding their strengths, opportunities for growth, and biases to behave in certain ways are more likely to be successful. They often build stronger, more mutually respectful relationships with a broader range of people; and this increases the probability of being able to address highly complex issues effectively. For these reasons, we pay close attention to HPI and HDS.

Problem Solving: But it isn’t all just touchy-feely. Problem solving and critical thinking skills are foundational in considering whether or not someone has the capacity to serve in a leadership role such as CEO. This is where the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal II (W-G) and the Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM) come into play.

The W-G helps us measure the following:

The insights gained from the W-G involve whether an individual can process highly complex information efficiently and make strategic decisions that take into account both short- and long-term consequences. However, the situation and the data regarding it are often ambiguous or incomplete; and this is where the RAPM is useful.

The RAPM helps us accomplish the following:

Combined, these two measures shed light on an individual’s ability to do the “systems thinking” or to “see the bigger strategic picture” that successful CEOs must have. In addition, they allow a CEO to prioritize issues and direct time and resources to those most critical concerns in a timely manner.

III. How To: Handle with Care

Given these robust, valid measures of both critical thinking and key personality factors, the question becomes how these assessments should be administered, used, and shared. The honest answer is: with flexibility, care, and compassion. That said, below are the core takeaways from our experience:

In closing: I’d like to thank Dr. Gary Lambert of Q4 Psychological Associates, not only for his significant contributions to this post, but also for his generosity of spirit in the sharing of his expertise and experience. Gary has been a great collaborator in Lock 8’s efforts to consistently improve our ability to set executives up for success. Beyond all of that, Gary is a pleasure and a lot of fun to work with.

“Digital transformation is a foundational change in how an organization delivers value to its customers.” -CIO

“Digital transformation is the process of using digital technologies to create new — or modify existing — business processes, culture, and customer experiences to meet changing business and market requirements.” -Salesforce

“The essence of digital transformation is to become a data-driven organization, ensuring that key decisions, actions, and processes are strongly influenced by data-driven insights, rather than by human intuition.” -Harvard Business Review.

Digital transformation is clearly a hot topic that is top of mind for many business leaders. But for small-scale SaaS businesses, digital transformation can feel like something foreign that “doesn’t really happen here.” Maybe this is because the topic is often portrayed as being unimaginably massive in its scope and implications (per the above quotes); whereas growth businesses must focus near-term. There’s also a “feast or famine” aspect to this depiction; it implies that digital transformation is best suited to either (1) old-school industries with a pressing need to modernize-or-die (the “famine” camp), or (2) highly capitalized, bleeding-edge tech firms pursuing reality-bending innovations (the “feast” cohort). Neither is typically the case in small-scale SaaS businesses, nor is this positioning particularly helpful. Rather, we observe digital transformation within small software companies as taking place one step at a time; and it helps to avoid overthinking it. In this way, digital transformation looks less like otherworldly “foundational change” and more like workflow automation that is pragmatic, targeted, and high-impact. Below are some simple examples from the real-world of Lock 8’s portfolio companies, followed by a few takeaways from these cases.

Marketing and Sales:

Product and Client Success:

These examples help illustrate a few key takeaways related to digital transformation. First, purists would likely argue that the above are all pedestrian / tactical in nature; and they don’t truly represent digital transformation. Fine — potato // po-tah-to. As long as they contribute to meaningful advances in our ability to execute, we don’t care what they are called. Second, tackling such minor improvements is habit-forming. We’ve found that implementing each of these small improvements tends to reveal other worthwhile processes that can be enhanced with minor automation. Third, every aspect of the business is a candidate for such project-lets. The examples above focus on a few departments, but we’ve seen a focus on Sales and Marketing (for example) very quickly shed light on potential workflow changes in Finance, HR, and other parts of the business. And, finally, we’ve found this works best when everyone is invited to play in this game. There may be one person who is particularly talented in business systems — and that person can lead execution — but process improvement ideas need to come from anywhere and everywhere within the org.

Just as every great journey begins with a single step, the road to digital transformation starts with some simple workflow automation — don’t overthink it.

The so-called Great Resignation was the topic of a previous post on this blog, and the following piece is a spin-off from that. That prior post focused on employee retention, as have so many recent articles. But we’ve experienced a separate challenge at Lock 8 that also bears discussion — how to get job candidates to actually leave their old company in order to join ours. To be clear, this isn’t a question of how to craft compelling job offers in an historically candidate-friendly market — that’s also rich topic that has been well-covered. Rather, this is about getting candidates who’ve formally accepted offers to actually follow-through on those commitments and show-up for Day 1 in their new company. Seems simple enough, but this challenge is proving to be non-trivial.

Admittedly, there is always risk associated with attractive candidates reconsidering their acceptances of offers, but we’ve seen an explosion of this practice lately. This appears to be yet another employer-focused disruption amid the broader upheaval of the Great Resignation — so much so that we’ve begun internally calling this practice the “Great Renege-ation.” This trend prompted us to consider tactics aimed at ensuring a higher “start-date” yield among accepted offers. Below are a few of the observations, lessons-learned, and things-we’ll-do-differently-next-time:

Bonus Tactic: While most of this piece focuses on closing candidates, it’s worth finishing with a downstream point about the new employee lifecycle. An element of surprise can be really helpful 6 months into someone’s tenure, such as providing an unexpected pay bump or options grant. Getting some re-enforcement that they are doing a good job and surprising them is a nice way to build stickier relationships with newer team members.

It’s a talent arms-race out there…anything we can do to get a leg-up amid the Great Resignation / Great Renege-ation is worth considering in this high-stakes game.

Countless recent media stories about the Great Resignation (including this, this, and this) make for compelling general reading. But for leaders of small-scale SaaS businesses, the Great Resignation is nothing short of greatly distressing. In a competitive environment that has long been engaged in a talent arms-race, record numbers of job quitters is truly harrowing news for the SaaS world. But this opinion piece from October by Karl W. Smith of Bloomberg (“Workers Who Quit their Jobs Could Improve US Productivity”) helps re-frame this inexorable movement in way that has informed Lock 8’s recent efforts to combat it. The following post hopes to briefly summarize Smith’s article and share some tactics that have shown promising early signs in the face of the Great Resignation.

Smith opens with this observation about the unprecedented level of churn in the job market: “at the heart of this phenomenon is a self-reinforcing cycle that has the potential to remake the labor market. As employers become more desperate to expand their workforce, job openings proliferate and workers become more confident in their options.” The reinforcing aspect of this cycle kicks-in when more workers quit, and their “reservation wage — the minimum they’ll accept — for taking a job” rises. This rise makes workers choosier, which cultivates even more desperation among employers…and, thus the cycle repeats and amplifies. What follows in the article is a macro-economic analysis and an argument in favor of creative destruction to the economy — “the cycle will be broken when employers turn their focus away from hiring more workers and toward increasing the productivity of their existing workforce.” Fascinating…and unassailable in the grand scheme. But what to do in the meantime and in our little small-scale SaaS corner of the world?

Like many articles on the Great Resignation, Smith’s focuses largely on low-cost jobs, macro-economic trends, and traditional definitions of labor, business expenditures, and productivity. While those concepts are universally relevant, variables like highly skilled workers, innovation, and capital efficiency seem more immediately impactful to the world of small software businesses. This brings to mind Daniel Pink’s insights regarding knowledge workers’ motivation being tied to autonomy, mastery, and purpose, a view we have ascribed to for years. This raises the related question: how are the same forces that are shaping the Great Resignation also influencing what employees truly value today?

First, money matters. There is unquestionably upward pressure on wages; and employers need to respond accordingly. But, as Karl points out in his article, “reservation wage” is not JUST about size of paycheck. Thankfully so — if it truly is all about the Benjamins, the little guy inevitably loses. No, we need to think more expansively about how to attract and retain talent. Building on the rock-solid foundation of autonomy, mastery, and purpose, we have observed that employees in late-2021 increasingly demand / appreciate: support, flexibility, and empathy. Accordingly, Lock 8’s portfolio companies have prioritized “other” initiatives, policies, and benefits that seek to embrace and advance these themes.

Attracting and retaining employees amid the Great Resignation is undoubtedly an ongoing challenge — and wage inflation is a reality in this situation. But, as Karl’s article articulates so well, increasing the productivity of the existing workforce is the clearest path toward optimizing performance…and embracing some “other” tactics through prioritizing support, flexibility, and empathy appears to be a path well worth pursuing.