This blog typically focuses on sharing observations from the twenty years I spent operating small-scale SaaS businesses. This post takes a different tack. It reflects more recent experiences, as I’ve transitioned over the past 18 months into the role of SaaS investor. That pivot has offered an exhilarating (and often humbling) opportunity to work with SaaS operators in a new way and from a different perspective. One of the things this experience has revealed is the need to be intentional about how investors and operators engage with each other. Failure to do so, I’ve learned, under-utilizes this potentially invaluable relationship and can lead to stale interactions. On the other hand, even a little bit of intentionality can drive more efficient and effective collaboration among company executives and board members / investors to the benefit of company performance. Below is a brief intro to the model we’ve adopted in recent months and how we’re using it to raise our game on this front.

We noticed that virtually all interactions between portfolio company executives and members of our investment team could be categorized based on two core questions. (1) Who is the owner / person responsible (portfolio company or investor) for leading a given activity or deliverable? (2) How much interaction does the exchange require? From these variables, an obvious 2x2 matrix emerged, as follows:

Because its useful shorthand to name quadrants of a 2x2 matrix, the following terms quickly attached themselves to each box.

And just as quickly, we realized that this simple schema neither represented reality, nor provided a model that meaningfully improved our communications. But, with a few tweaks, it became valuable quickly. The trick was understanding that a binary notion of ownership makes perfect sense for artifacts or deliverables but makes less sense in connection to in-depth discussions about complex topics. To recognize this reality, the 2x2 morphed into something a bit more complex; and the following model came forward:

This was a game-changer for a few reasons. First, it became easy to plot virtually all our interactions / exchanges somewhere within this model. Below is a small example with just a few of the items on which our operators and investors / board members collaborate or exchange information:

Second, this framework established some shared language, through which we gained immediate communications efficiency. It became simple, when discussing an initiative or a deliverable, to identify the box it was believed to occupy…and to quickly uncover and address any areas of misalignment. When discussing a potential topic or project, it has become common for us to rely on shorthand such as, “I think this is a Box 4 topic, do you agree?” This has squeezed-out some previously existing room for confusion. To avoid all doubt, we use the following numbering system:

But the biggest benefit by far has been to raise our awareness of the amount of time and energy spent in each box…and our sensitivity to wasting time in the wrong box on a given topic. For example, in the first few months after an investment, we spend a good deal of time in collaborative discussion (Box 2: Shared Strategic Planning). That makes a ton of sense for many reasons, particularly during a period where there is a lot of shared learning around complex topics and where planning occurs through a collaborative and iterative process. But that can be really time consuming. And, as the company moves into more of an execution mode, it becomes advantageous to migrate operator-investor interactions more into boxes 4–7. When recently asked by a portfolio company CEO about a particularly thorny product-related issue, I reflexively suggested that we get in a room to discuss. Instead, he responded, “In this situation, it would be more valuable for me to hear a summary of your lessons learned on this topic, can we just make this a Box 5 presentation from you guys?” I was happy to comply; since we are all aligned around optimizing company performance. This kind of directive request helps us to arm operators with whatever support they need to succeed in the market.

This whole approach reminds me a bit of the balanced eating plate graphics that we learned about in Health class as kids. The general concept is timeless, even if the exact categories and proportions will forever be a subject to ongoing examination and debate.

In both scenarios, what’s most important is that there is (1) a healthy balance, (2) a framework for making good, intentional choices, and (3) a useful check against simply defaulting to the part of the plate — or the type of interaction — that satisfies our craving in a given moment. Finally, as the saying goes, variety is the spice of life. Our experience is that the same is true when it comes to interactions between operators and investors — a little planning and a bit of balance / diversity leads to more efficient and effective interactions that are also just generally easier for everyone to swallow.

It’s easy for leaders to get caught up in the day-to-day of running small-scale businesses. Particularly during challenging times, it can take all our energy just to “keep the wheels on the bus.” Unfortunately, a casualty of operating in this mode is that we tend to focus far less on the long-term composition of the team — who’s actually on the bus, whether they are in the right seats, and who should be getting on / off at upcoming stops. This is hardly surprising — such planning demands both discipline and foresight. It’s also difficult to get right: organizational design is quite complex, and according to research from McKinsey & Company, less than 25% of organizational redesigns succeed. With that in mind, this post can’t begin to scratch the surface on this rich topic. Rather, it simply introduces a quick-and-dirty exercise to help leaders elevate and think proactively about their organizational “bus” both now and in the future. What follows is a description of the exercise (the “What”), some tips around its execution (the “How”), and some observations about its effectiveness (the “Why”).

The What: The exercise is quite simple and builds upon something that virtually every organization already has available in some format — a current org chart. Using that as a starting point, the leader creates a series of hypothetical future org charts for the business. Specifically, (s)he creates four new / additional org charts, each representing successive six-month intervals into the future. This results in a total of five prospective org charts, essentially five snap-shots that look forward two years, six-month at a time. The five org charts are as follows:

The How: This really is a simple exercise, so there is no need to overthink it. But a few pro-tips can’t hurt; and the following will help make the exercise even easier and more impactful:

The Why: The primary benefit of this exercise is hopefully clear: it is a low-effort way for a leader to plan out with intention and purpose how an organization will grow over time. It works well because it doesn’t require any special skills, resources, or training; and it is something leaders can easily do on their own a couple times of year with a moderate amount of discipline in a short period of time. A few of the side-benefits, and why this exercise works in achieving them, are outlined below:

In closing, this exercise is largely about interdependency between the business outcomes and the people-related aspects of organizations. Leaders generally have a keen sense from a mission and financial perspective of where they want their businesses to be at various points in the future. What we tend to be less good at is identifying and aligning the roles and skillsets necessary to achieve those objectives. Yet, they are completely interdependent — the envisioned goals, and the difficult-to-define team / structure required reach them. This exercise aims to help navigate the organizational side of things. Hopefully, it can help leaders develop a far-seeing view of who should be “on the bus”…and provide everyone a much smoother ride toward the desired destination.

The “law of holes” was drilled into my head as a kid; and it is sound advice. The problem, of course, is proactively identifying whether and when you are actually digging yourself a hole.

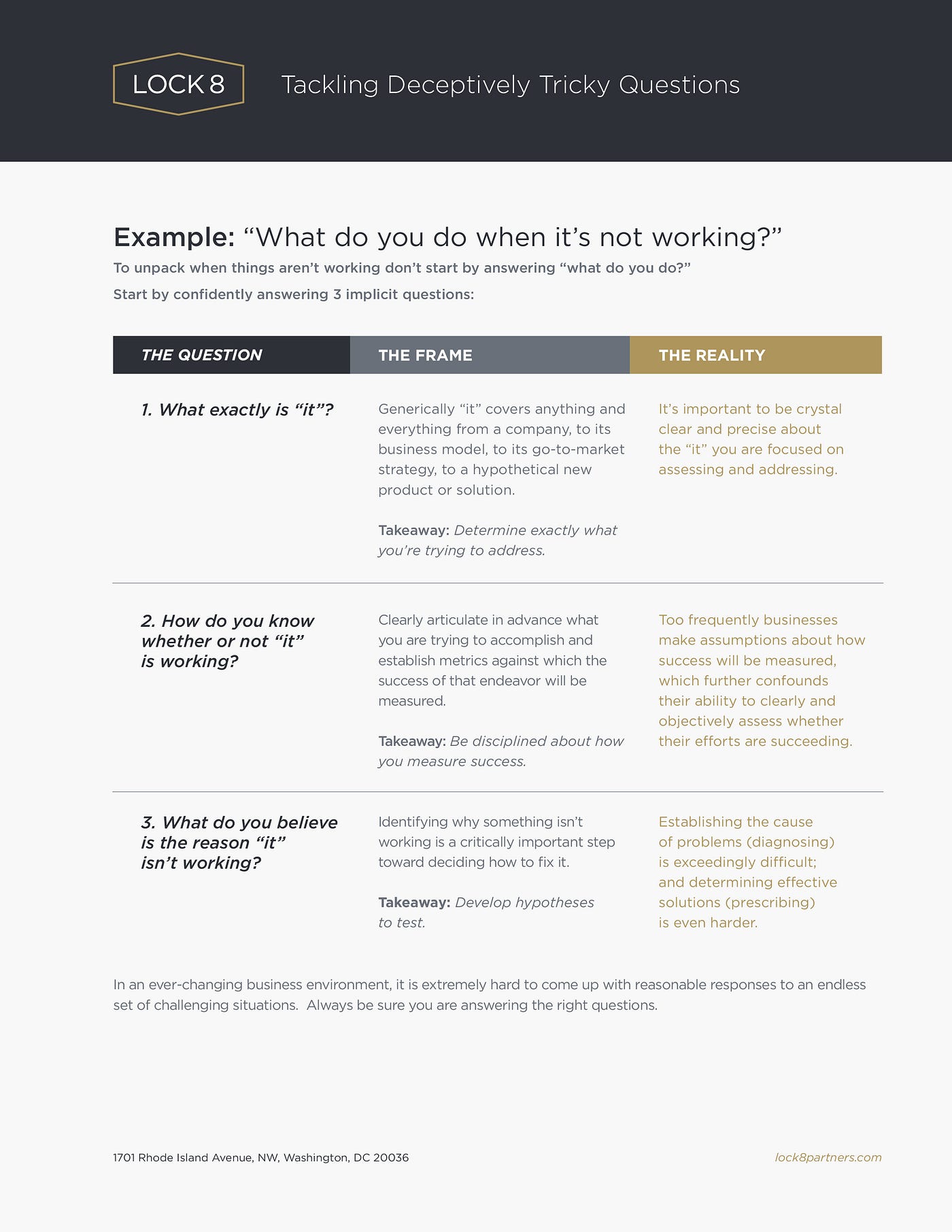

I was recently reminded of this dynamic while visiting with the impressive leadership team of a 40-ish person SaaS company. We had met to discuss a range of topics relating to the life cycles of growing businesses. One person posed a seemingly straightforward question to the group that resulted in an immediate and spirited exchange: “What do you do when it’s not working?”

As a rich discussion unfolded, I remained silently stuck in the subtle, complexities of the question. While the debate whizzed past, I did what I often do when stranded in such situations — start to draw. The graphic below is a more formalized version of my notes and thought process from that session. It’s also an attempt to offer a simple approach to tackling this deceptively tricky question, and potentially others like it that prove surprisingly elusive to wrangle.

With those fateful words, the meeting ends on seemingly solid ground. Unfortunately, too often a team’s commitment begins to erode almost immediately after adjourning. In these scenarios, a corrosive force is hard at work, devastating teams and laying waste to even the most solid plans. It’s called re-trading, and it takes place when someone(s) revisits a settled decision with the intent to change plans after the fact. This post attempts to shine a light on the toxic team behavior and offer some thoughts for combating it. But first let’s take a step back and offer some context:

“Disagree and commit” is a management principle which states that individuals are allowed to disagree while a decision is being made, but that once a decision has been made, everybody must commit to it. According to Wikipedia, this principle has been attributed to such icons as Andy Grove, Scott McNealy, and Jeff Bezos. Whatever its true origin, it “pinpoints when it is useful to have conflict and disagreement (early states of decision-making, but not after the decision is made). It is also helpful in avoiding the consensus trap, in which a lack of consensus leads to inaction.” In general, this principle is useful in organizations that value different perspectives but have finite resources to pursue seemingly unlimited ideas (i.e. in most growing SaaS businesses). It works well, so long as people commit in good faith to a plan and then maintain that commitment even in the face of inevitable adversity. It fails miserably when people’s commitment wavers and they seek to revisit the original decision via a re-trade. The re-trade can present itself in any number of different forms, including:

Whatever the precise form, re-trading reflects an unhealthy team dynamic. Interestingly, re-trading rarely takes place within the context of an open setting (i.e. a leadership team meeting), but rather often in 1-on-1 conversations behind closed doors. This is a useless waste of time. It sows the seeds of mistrust (what are they whispering about in there?). It creates factions and unproductive conflict. Even worse, these discussions often spill over beyond the attendees of the original meeting. In this way, leadership team members can dangerously undermine their peers, which completely freaks out the broader team (no one’s happy when the “adults” bring “the kids” into their fight). Needless to say, if these whisper-campaigns gain traction, they can completely derail the original agreed-upon plans. Left unchecked, these side conversations can also have a debilitating long-term effect on future decisions. Specifically, if people believe that they can re-visit decisions after the fact without negative consequences, then they may be incented to simply lay-low during initial debates and surreptitiously seek to get their way later-on. In short, once re-trading becomes normalized, no future decision will ever be safe from the threat of a re-trade.

On the contrary, in his classic book “The Five Dysfunctions of a Team,” Patrick Lencioni offers a succinct description of how truly cohesive teams behave:

Lencioni’s model also offers insights regarding ways to combat the re-trade. As I often say, there is no cure-all for human behavior. But if re-trading blooms in darkness, then sunshine is the best disinfectant. Specifically, pre-emptively calling out the dangers of re-trading goes a long way toward helping teams arm themselves against it. Unlike Voldemort in the Harry Potter series (“He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named”), openly acknowledging the potential for re-trading raises people’s awareness of and vigilance against it. Naming and shaming this behavior can give team members language to identify and resist peers’ efforts to engage in after-action 1-on-1 gripe sessions (a central means to waging a re-trading initiative). It also allows leaders to establish criteria for when it is appropriate to re-open past decisions. Specifically, facts and circumstances do change over time. And, if the realities on the ground justify it, then decisions absolutely should be reconsidered by the team. By establishing this as the one reason to re-open prior decisions, leaders can set a high bar for when / how / why plans can openly be re-litigated. Finally, because an ounce of prevention truly is worth a pound of cure, Lencioni’s model offers good guidance on how to address the root cause of re-trading. Maniacal focus on building trust and embracing unfiltered conflict early-on in decision-making processes will always be the best way to avoid downstream re-trading and all its devastating effects.

“So, we’re all in agreement, right? Great, let’s do it.”

The people-situation at the outset of my first CEO gig was rocky. We needed to grow and up-skill the team but were in no position to attract top talent. The company was midway through a sizable pivot, cash was dwindling, and our immature SaaS platform needed serious investment. Economic realities had dented our company valuation, making stock options an ineffective recruiting tool; and our dreary, subterranean office-space certainly didn’t help. So, we staffed-up the way so many other start-ups have done in similar situations: we hired eager, inexpensive recent college grads and gave them tons of responsibility. They loved it and responded with energy and enthusiasm. But they also desperately needed training, guidance, and consistent coaching. So, out of necessity, we got good at that.

Specifically, we grew adept in an area that is critical to any growing SaaS business: delegating meaningful work to entry-level employees and providing them with enough scaffolding to aid their near-term success while also supporting their long-term growth. This post addresses one small aspect of this broader challenge that so many growing SaaS businesses face: how to assign projects to less-experienced professionals in a way that works well for individual contributors, for their managers, and for the overall company.

First things first, it really helps for the company to identify one named person to be responsible for assigning work to any given entry-level employee. This may sound obvious, but is certainly not a given in many fluid, early-stage businesses. Among the benefits of this simple step is that it helps the employee avoid the complex, sometimes fraught responsibility of balancing simultaneous commitments to multiple senior people. It also ensures that assignments are given and received via one consistent voice, which avoids a lot of miscommunications.

Beyond the above, though, we’ve found the most important “must-do” is to support every assignment in writing. Even better, do so using a standardized format. A standardized format offers a structured, easy-to-understand written summary that codifies that project for the junior team member. Templates can take any number of forms; and below is an explanation of the template we’ve been using for this purpose at Lock 8 Partners:

Having introduced this tool, I feel obligated to acknowledge that any tool is only as good as a person’s ability to use it. And, while that topic is likely another blog post altogether, we have observed a few simple rules of thumb that help to successfully leverage this tool, including:

In closing, I need to acknowledge that there are no silver bullets to any human challenge; and this template is no panacea. Helping less experienced employees mature into seasoned professionals requires thoughtful on-boarding, purposeful training, consistent coaching, caring mentorship, and so much more. But because these initiatives often require more time and resources than are available in many small-scale businesses, we’re hopeful that this project template can offer a useful tool to help in building and growing your team.

In 2014 I found myself leading a SaaS business with a problem: how to hire executives to manage our company’s significant growth. It was a good problem to have, for sure; but it was still a problem. So, we scoped roles, identified job qualifications, established interview processes, activated our networks, and engaged recruiters. But mostly, we hoped. We hoped like crazy to avoid making a bad exec hire, which we knew would leave a trail of pain for months to come.

I was reminded of this personal experience last week while discussing the topic of exec hiring among a small group of entrepreneurs/operators. People consistently shared experiences of having anxiously faced, often unsuccessfully, this quite common business challenge. One entrepreneur helpfully shared the “GWC” framework that he had discovered while implementing the EOS Model outlined in the book Traction. The GWC framework is explained here, but the gist is that you should only hire people who:

In considering this framework, I realized that many businesses tend to over-index on the C (Capacity) in the hiring process. No surprise there; it’s understandable for us to optimize around finding someone who has the skills, experience and capabilities to get the job done. In fairness, many organizations fully appreciate the importance of culture and fit; so, the G (Get it) also gets strong consideration. But the W (Want it) often gets lost in the shuffle. Perhaps we are prone to assume or overestimate the degree to which someone wants to work at our companies. For whatever reason, the W receives less thoughtful examination compared to diligence around the G and the C. Reflecting on dozens (hundreds?) of hires over the last 20 years, I’m struck by how backward this is.

When I think about the truly great hires we’ve made, virtually every one of them had a very high W-factor. These are the folks who would run through walls, and whose desire was infectious. Conversely, I suspect that we can all recount failed hires where the C (and even the G) were very persuasive…but the W just wasn’t quite there. I’ll go one step further and say that a hire with a strong W can bridge gaps in their C and G (“where there is a will, there is a way”); but the converse simply isn’t true. Precisely why someone “wants it” is irrelevant, and the W can come from a wide range of circumstances; but it absolutely needs to exist.

To paraphrase the Rolling Stones: You can’t always get what you want; but hiring “want it” will definitely help get what you need.

If humans are truly social animals with an innate need to interact with others, then why do we hate meetings so much? And if meetings are bad, then why do we find extended offsite sessions even more brutally intolerable? With offsite planning season soon upon us, such questions are worth asking and answering…and just maybe…offering some tips to ease the pain.

First things first, meetings are unbearable for thousands of reasons. But they all come back to one simple idea: opportunity cost. We’re all busy, with far more responsibilities than time to manage them. And we’re haunted by the excruciating realization that time spent in meetings could be far better invested in other pursuits. But what if that didn’t have to be the case?

Much has been written about ways to make meetings more effective, with innovative companies like Google, Amazon, and Bridgewater each having its own unique approach to meeting management. This post attempts to contribute to that impressive body of work by offering one simple tactic that has consistently helped improve our own meetings and offsites over two decades and many businesses.

We call it a “pre-mortem,” and it’s based on the concept of a “post-mortem.” A post-mortem is an examination of a dead body to determine the cause of death. In the context of business, a post-mortem is a common project management practice in which a critical retrospective is performed to learn what went right and (primarily) wrong in a given initiative. In other words, what was the cause of death? We’ve taken that same concept and put it at the beginning of the process when hosting a meeting. A pre-mortem pre-emptively asks the uncomfortable question: what could possibly kill this meeting?

The way it works is simple: the meeting leader starts the meeting by asking each attendee what would make the session an abject failure for them. Then, each person let’s fly with their worst fears about how the meeting could turn into a slow-motion car crash. The meeting organizer captures the shared comments on a large, visible white-board or sticky-note. Next, the group takes the time (usually 10-ish minutes) to discuss the comments, often with clarifying questions and conversations about how these failures might occur…and what can be done to avoid them. Importantly, the group commits to work together to avoid the negative outcome. The meeting ultimately commences and proceeds in an otherwise typical manner, with the pre-mortem being the last item revisited (again, for about 5–10 minutes) prior to adjourning. We’ve found the results of this to be…well…really good. Is it magic? No, nothing is. Does it help to make meetings far less brain damage? Absolutely.

Before offering some thoughts on why this tends to work, let’s first explore a “dirty dozen” of the comments that commonly appear on these lists. In no particular order, responses include:

There are countless other issues that people have with meetings, but this is a pretty good representative sample.

Now…why is this approach so effective? One undeniable reason is that naming problematic behaviors or practices tends to put people on notice — don’t be this person! More than that, it gives us a spoken, commonly, acknowledged, up-to-the-minute benchmark against which to hold people accountable if they violate the boundaries. This also provides a language and a tool to gently call people out when they do fall afoul (it’s easy to simply point to the sticky-notes when someone flagrantly blows through item #7). More than any of these though, people in growth businesses tend to “hate to lose” far more than they “love to win.” Said another way, it’s not enough to enumerate what GOOD meeting practices are — people won’t change their behavior to meeting that threshold. But no one wants to be the person who obviously fails to live up to basic standards of meeting professionalism. So they tow the line…and the collective behavior change makes for massively improved meeting outcomes.

Give it a try some time; and please let me know how it goes, what you learn, or how we can further refine and improve this approach.

Cats and dogs. Oil and water. Hatfields and McCoys. Some things just don’t play well together. In fact, they seem almost purpose-built for conflict. I was reminded (again) this past week that the SaaS version of such predictable tension is the running feud between Sales and Client Success departments. There is undeniable and inherent tension between the two groups, and it’s easy to see why: the remit of Sales is to maximize bookings / hit targets in the immediate-term, whereas Client Success is responsible for turning every customer into raving fans long into the future. But this doesn’t need to lead to incessant battling. In fact, I’ve found that a few simple exercises can go a long way toward disarming the inter-departmental combat.

1. People Are People

I’ve observed that a fair bit of this conflict stems from a simple value-perception problem. Specifically, bookings are valued very highly in young SaaS businesses, with new sales (and often Sales people) celebrated as a life-line during a company’s fragile, early days (I wrote a bit about this here). Somewhat irrationally, those same organizations tend to be less overt and unrestrained in celebrating renewals, which lead to multiple years of recurring revenue. The predictable result is inequity in terms of how team members in Sales and Client Success perceive they are valued in the business. This, in turn, can breed resentment and conflict. A simple solution to this pervasive problem? Have the groups talk about it. But, to avoid reverting into counter-productive naming and shaming, be sure to do it in a thoughtful and structured way. I particularly like the following simple exercise:

With each person using a sheet of paper, ask people from Sales and CS, respectively, to privately rate and record on a scale of 1–5 their responses to the following two questions:

Then have them exchange papers and discuss. No matter the written responses, substantive and productive discussions generally ensue. Why?

2. We Mock What We Don’t Understand

Let me say that I just don’t buy the argument that Sales and CS people are just intrinsically different and incompatible. Rather, my experience is that they both want the same things — to win in the market, for their customers to be successful, and to thrive as a company and as individual professionals. The two groups just define and prioritize those objectives differently, (which is hardly surprising, given their respective areas of responsibility).

Beyond that though, the groups generally just don’t understand each other well. Again, this is unsurprising: SaaS businesses are fast-paced, resource-constrained environments. So, it’s far too rare that people receive adequate training on their own job function, let alone on the responsibilities of others. As a result, people have only a vague understanding of others’ work and almost no appreciation for the things that can make that work difficult or frustrating. And while people are hyper-aware of what they themselves produce, they are far less cognizant of their cross-department colleagues’ work product. The exception to this, of course, is when their peers’ actions make their own job more challenging…in which case the cross-department ceasefire is cancelled and hostilities resume. The painfully obvious (but difficult to execute) solution: educating people about the inter-dependent nature of their departments. For this, I like an exercise that centers around what each job function (a) produces and (b) consumes from the other.

Instructions: Ask members of Sales and Client Success to work together to identify 3–5 things for each of two categories:

I specifically like to create a grid where groups can brainstorm in isolation about what one department produces for the other. And then you do the same thing for what that department consumes from the other. Then switch departments. Because people from different departments are working as one group in this exercise, it tends to highlight just how different their perceptions / responses / pain points are at the outset…and how much and how quickly they learn to bridge the gap. I’ve focused this on Sales and CS here, but I like to do this one across all departments. The end result of this is a Give-Get Grid, which I wrote a bit about here, and which I’ll go into in more depth in a future post.

3. Our Strengths are Our Weaknesses

I’m a fan of the Gallup StrengthsFinder assessment for many reasons. Among them is the fact that it gives us language to call someone out for counter-productive behavior, but to do it in an inoffensive way. Specifically, StrengthsFinder is a diagnostic that allows people to identify what their core strengths are in terms of how they think, work, and view the world. Like many diagnostics, the explanatory write-ups for each of the framework’s 34 Strengths tend to resonate clearly with people when they receive their personal test results. And one of the most valuable parts of the assessment, for our purposes here, is how it convincingly and pragmatically points out this truism: our greatest strengths — left unchecked — frequently also present themselves as our great weaknesses. For example, “people exceptionally talented in the Activator theme can make things happen by turning thoughts into action. They want to do things now, rather than simply talk about them.” This is awesomely valuable when the situation demands speed. But this inclination can be counter-productive in situations that require great care, planning, or coordination. Likewise, Activators can be incredibly aggravating to those for whom Focus — “following through and making the corrections necessary to stay on track by prioritizing, then acting” — is their top strength. In such a case, it is undeniably better for the Focus person to politely / humorously ask the colleague to “tamp down their Activator tendency” than it is to tell them that the whole team wants to strangle their impetuous, hyper-active, cowboy throat. You know how these conversations can go…

Give People a Pass:

In closing, I want to broaden the scope beyond Sales and CS to cover all departments; there is a degree of tension among all of them, and they can all stand to examine how they intersect. I also want to acknowledge that these minor tactics / frameworks may be powerless in the face of true interdepartmental dysfunction or deep personal animosity among team members(!). But if that is the case, then more serious measures are likely needed to change the team…or change the team. That said, I’ve observed that most issues arise in an environment where different departments truly do share goals and respect for one another — they just need help getting aligned.

In such cases, we all need to step back and just give people a break. That’s right, give them a pass, and lay down your inter-departmental arms. Recognize colleagues’ perspective and take the high road, already! The Hatfield-McCoy thing does no one any good, and more importantly, isn’t worth the distraction from the ever-pressing needs of clients and the business at large. Frankly, it’s a pure waste to dwell or be mired in it. Use it; work it to affect mutual advantage and company success. There is usually a way. Find the leverage. It’s there to be found.

The other day, I re-discovered this great post by Theo Priestley of Forbes explaining why “Every Tech Company Needs a Chief Evangelist.” Re-reading this after a few years brought up positive thoughts about this role and fond memories of having encouraged a particular team member to consider becoming a technology evangelist back in the day.

Some backstory: at the time, the person in question was in the wrong role — one that was important to the company, but which did not play to her strengths. At the same time, our small-scale company and product category needed a strong spokesperson — someone who not only believed in our company’s mission and solution, but who could expertly recruit others to share in our enthusiasm. We were fortunate that this hiding-in-plain-sight “evangelist” had been with the company from its earliest days, and had all along been winning followers to our cause — far in advance of officially assuming the title “evangelist.” What follows is a compilation of questions and observations about that experience and more generally about the evangelist role in SaaS businesses.

So…what exactly is a technology evangelist?

Truly effective evangelists play a special role in the growth of SaaS companies. Whether or not they bear that specific title, you probably have encountered these people along the way. You know these folks when you meet them by the excitement they feel to tell you about what their company brings to the world. As they speak, you find yourself getting swept up in their enthusiasm. They are completely genuine in their belief that the work of their companies will change the world. They can articulate clearly and authentically how the world will be different once their companies have reached critical mass in the marketplace. They are intimately familiar with the technology behind your company’s products, but where they truly get their energy is in discussing the problems those products solve for people. This, more so than any technical knowledge, is what speaks universally and authentically to executives, IT professionals, finance and operations folks, and many others.

Who makes a good technology evangelist?

It doesn’t matter what your company does, the role of technology evangelist requires a unique blend of talents and traits. Once identified, these traits should absolutely be cultivated. What evangelists bring:

What does a tech evangelist actually do (and why would we need one)?

The specific role of the evangelist can vary, depending on your business and the markets / customers you serve. In my experience, the very best evangelists are often extroverts and road warriors. These folks derive energy and joy from giving presentations at industry conferences and providing direct support to customers, as well presenting dozens of webinars each year (full disclosure, this is NOT at all my own personal super-power, and it would consume a massive amount of my mental energy if I was solely responsible for this). Your evangelist might be a producer of other content — from customer-facing training and support materials, or wrap-around content relevant to your industry, to conducting related research to share with your market.

How can we best support / unleash our technology evangelist(s)?

What is important organizationally is to support the evangelist in her / his zeal for spreading your company’s message, without introducing too many constraints. This can admittedly be hard to rationalize in resource-constrained environments, but the outcomes often more than justify this investment. The role of the evangelist is to galvanize — which can absolutely have a profound and positive net impact across the business — measured in bookings, qualified leads, organic web traffic, brand strength and resilience, quashing the competition, attracting and retaining top talent, and more. Your evangelist might be asked to carry a sales quota, or have targets for establishing key partnerships. Or your evangelist might be measured on digital demand-generation metrics — on how much organic traffic to your website is produced from the evangelist’s written / audio / video content. But, be careful — trying to saddle these people with too narrow of a goal-set can stifle their creativity and sub-optimize their efforts.

As Theo Priestly pointed out in his Forbes post, “Evangelism creates a human connection with buyers and consumers to technology way beyond typical content marketing means because there’s a face and a name relaying the story, expressing the opinion, and ultimately influencing a decision.”

So where do you find a technology evangelist?

Chances are, you may have a burgeoning technology evangelist already in your midst. Many employees of small-scale companies have innate enthusiasm for your mission. If cultivated, this energy could become fully realized evangelism. You want to find someone who can be utterly convincing without it ever seeming like a “sales pitch.” You want the individual who can articulate the power of your technology, but in ways anyone could access and understand. You want the evangelist to be someone who has already “won over” a group of devoted followers — fellow staff members, customers, investors, media representatives, and others.

What one mistake should we avoid regarding technology evangelist(s)?

Be decisive, but don’t force it. Like so many things in the small-scale SaaS world, finding an evangelist seems to work best when it happens in an organic way, whereas trying to force it by quickly recruiting for the role can end badly. Often someone just kind of eases into these activities and ultimately into a more formalized role. This was the case with the outstanding technology evangelist described above, which was certainly fortuitous. Then again, when you have the right person, don’t be afraid to take the leap and make the commitment. These folks are never happier than when preaching your company’s gospel; and they can definitely accelerate your your efforts to make your mark on the world.

In dynamic, growing organizations, the relationship between the CEO and CTO is critically important. Unfortunately, this partnership often doesn’t get the attention it deserves. And, in some ways, it is a relationship that is set up with inherent tension. So, what are some things the CEO and CTO should be making time to talk about?

This was a topic I was invited to cover, from a CEO’s perspective, at a recent gathering of CTO’s. Below is a series of short videos that capture and share some of the main points from that session.

Introduction: What is your CEO thinking (and likely not telling you)? — 7 minutes

Part 1: Re-thinking Investment: Building a Dream Home — 3 minutes

Part 2: Bridging the Gap: From Vision to Story Points — 4 minutes

Part 3: Doing vs. Building: The Whole People Thing — 4 minutes

Part 4: Nurturing Purpose: Love Languages and Left Brainers — 3 minutes

Part 5: Surviving Communications: Avoiding Death by Meeting — 5 minutes