The television series Undercover Boss has been a guilty pleasure of mine for years. Now entering its eleventh season, the show features “high-level corporate execs (who) leave the comfort of their offices and secretly take low-level jobs within their companies to find out how things really work and what their employees truly think of them.” For cringe-worthy viewing, this one totally hits home for me.

But I also like the show’s more serious theme of “walking a mile in someone else’s shoes” in order to deeply understand that person’s experience. At Lock 8, we’ve adapted this concept to help provide insight into a key focus area for small-scale SaaS businesses. Whereas Undercover Boss leverages this approach to offer candid employee-level views into the internal workings of companies, we hope to shine a light on the experience a customer has when evaluating, selecting, and adopting a B2B software solution.

On the surface, this is a straightforward endeavor, involving a few simple steps:

Simple enough, right? Not really. Like so many things, this is easy to do poorly, and extremely difficult to do well. To help make it easier, this post will share a few tips relating to each of these deceptively challenging steps.

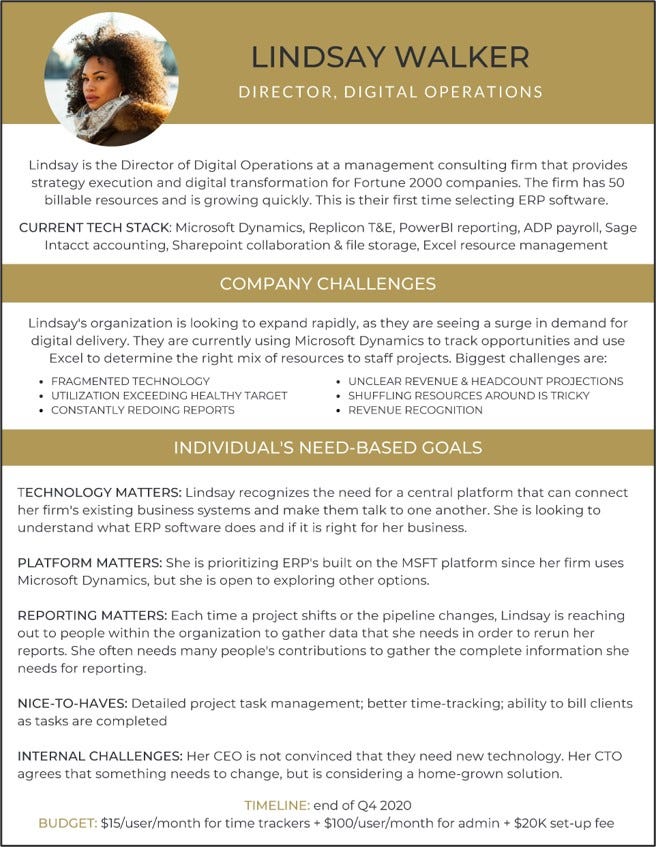

1. Pretend You Are a Prospect: At its most basic level, this is a role-playing exercise, so it’s absolutely critical to play your role well. This may be relatively easy for the undercover bosses referenced above (they get a cover legend and a disguise; and they go), but it is more complicated to get inside the mind(s) of a purchasing committee for a large and complex corporate enterprise. We’ve learned that it is definitely worth investing the time and effort to make it real: have a dossier, real personas, real business problems you’re solving for, deadlines, budget constraints, and even political motivations. Even go so far as to designate a few people to play different decision-maker roles. Balance the company profiles to reflect your current (vertical) targets, your buyer personas spectrum and the maturity of organization using your solution. Marketing absolutely should help develop these resources. Here’s a snapshot of just part of a dossier created by a portfolio company that recently executed such an initiative.

An additional point about this step: BE OPEN! Unlike the undercover bosses, for whom secrecy is paramount, this should NOT be a clandestine endeavor. The reality in software companies is that everyone somehow touches the customer experience. Likewise, our experience is that people in early-stage SaaS business are all operating in good faith, so there is no need to trick anyone or attempt to trip them up. Rather, everyone needs to know you’re undertaking such a journey; and each functional area needs to be part of the process. Now…you may need to make the case: why it’s important; why we need to get it right; who’s involved; what we’ll be doing; how we’ll share feedback. But these are all further arguments for doing this out in the open. Equally important: everyone at the company should hear later what was discovered, and to view the information as a learning opportunity, not a judgement. Nothing makes people more nervous than being excluded from understanding what’s happening behind the scenes or feeling like this is a test.

2. Go Through the Steps: Uh…what steps? Whereas most businesses have established a sales process with related stages and activities, these usually assume a company-centric approach, and overwhelmingly ignore the customer perspective. Customers’ motivations / activities / dynamics are effectively infinite, so identifying their purchasing steps can be paralyzingly complex. To simplify, we like to organize our efforts around “major stages” of the customer’s lifespan with a software solution. Although every product / system / technology is unique, there is a relatively small number of macro-phases on the customer journey; and these are generally consistent across different solutions. The purpose of the mental model and accompanying graphic below is to align perspectives, offer a shared vocabulary, and provide structure to the exercise.

On the principle that a picture is worth a thousand words, I’ll hope this graphic is self-explanatory. In summary, as we engage in countless customer “buying” and “owning” activities, and we organize them into these six phases: (1) awareness, (2) evaluation, (3) decision, (4) on-boarding, (5) use, and (6) advocacy. One note of caution: for complex solutions, this may end up being a grueling multi-month process. It’s important to know what you are signing up for in advance…and what your customers are going through to buy / use your products.

3. Record Your Experiences: A disciplined collection of notes will generate consistency of insight and evaluation. With more than one person involved the experience, it’s important to provide a consistent way to gather intel and feedback. That said, this doesn’t require over-thinking; and a simple note template suffices. We like an “Experience and Expectation” framework (“what did I expect?” and “what did I experience?”) to structure things. Then, just codify the experience in a linear way — capture in detail and in chronological order what happened and how it impacted the buying / owning processes outlined above.

4. Articulate the Ideal: It’s nearly impossible to simply dream up the ideal client experience, just like it is unheard of to nail product-market-fit on version 1.0 of a solution. Instead, it pays to inspect and adapt. Thankfully, the early steps of this exercise, and the current-state baseline they provide, offer an awesome foundation from which to iterate toward a vastly enhanced client experience. As a result, this step can be as simple as revisiting every step along the journey and answering the following question: “what would have made this much better?” In the best case, this can lead to a wholesale re-thinking of the journey; at a minimum, it will radically improve the existing steps of the experience.

5. Identify gaps; build a plan: For the activators in the crowd, this is the payoff where you can begin to implement necessary improvements. But be careful about succumbing to temptation. It is alluring to focus energy on an ad hoc basis to address the low hanging fruit that can be fixed easily. The problem is that this approach can break any number of existing processes that — although they may be sub-optimal — generally work today in the context of the current approach. So be careful about what you choose to “fix” as a one-off — it could just break other areas of your process. Although it requires more patience and offers delayed gratification, an orchestrated program overhaul will undoubtedly yield more substantive improvement of the overall client experience. Make a plan and take your time in executing it. Our experience is that the “customer experience re-engineering” project to come out of this exercise may take months or even years to implement.

As with most pressing, cross-company business issues, initiatives like creating an awesome CX Journey can take on a life of their own. Proceed with caution here; ensure that anything and everything you chose to do ties back to your overarching business needs. Such an effort must involve more than just the bosses; and there is no need to go undercover — doing so will allow companies to walk in their customers’ shoes…a journey well worth taking.

This blog typically focuses on sharing observations from the twenty years I spent operating small-scale SaaS businesses. This post takes a different tack. It reflects more recent experiences, as I’ve transitioned over the past 18 months into the role of SaaS investor. That pivot has offered an exhilarating (and often humbling) opportunity to work with SaaS operators in a new way and from a different perspective. One of the things this experience has revealed is the need to be intentional about how investors and operators engage with each other. Failure to do so, I’ve learned, under-utilizes this potentially invaluable relationship and can lead to stale interactions. On the other hand, even a little bit of intentionality can drive more efficient and effective collaboration among company executives and board members / investors to the benefit of company performance. Below is a brief intro to the model we’ve adopted in recent months and how we’re using it to raise our game on this front.

We noticed that virtually all interactions between portfolio company executives and members of our investment team could be categorized based on two core questions. (1) Who is the owner / person responsible (portfolio company or investor) for leading a given activity or deliverable? (2) How much interaction does the exchange require? From these variables, an obvious 2x2 matrix emerged, as follows:

Because its useful shorthand to name quadrants of a 2x2 matrix, the following terms quickly attached themselves to each box.

And just as quickly, we realized that this simple schema neither represented reality, nor provided a model that meaningfully improved our communications. But, with a few tweaks, it became valuable quickly. The trick was understanding that a binary notion of ownership makes perfect sense for artifacts or deliverables but makes less sense in connection to in-depth discussions about complex topics. To recognize this reality, the 2x2 morphed into something a bit more complex; and the following model came forward:

This was a game-changer for a few reasons. First, it became easy to plot virtually all our interactions / exchanges somewhere within this model. Below is a small example with just a few of the items on which our operators and investors / board members collaborate or exchange information:

Second, this framework established some shared language, through which we gained immediate communications efficiency. It became simple, when discussing an initiative or a deliverable, to identify the box it was believed to occupy…and to quickly uncover and address any areas of misalignment. When discussing a potential topic or project, it has become common for us to rely on shorthand such as, “I think this is a Box 4 topic, do you agree?” This has squeezed-out some previously existing room for confusion. To avoid all doubt, we use the following numbering system:

But the biggest benefit by far has been to raise our awareness of the amount of time and energy spent in each box…and our sensitivity to wasting time in the wrong box on a given topic. For example, in the first few months after an investment, we spend a good deal of time in collaborative discussion (Box 2: Shared Strategic Planning). That makes a ton of sense for many reasons, particularly during a period where there is a lot of shared learning around complex topics and where planning occurs through a collaborative and iterative process. But that can be really time consuming. And, as the company moves into more of an execution mode, it becomes advantageous to migrate operator-investor interactions more into boxes 4–7. When recently asked by a portfolio company CEO about a particularly thorny product-related issue, I reflexively suggested that we get in a room to discuss. Instead, he responded, “In this situation, it would be more valuable for me to hear a summary of your lessons learned on this topic, can we just make this a Box 5 presentation from you guys?” I was happy to comply; since we are all aligned around optimizing company performance. This kind of directive request helps us to arm operators with whatever support they need to succeed in the market.

This whole approach reminds me a bit of the balanced eating plate graphics that we learned about in Health class as kids. The general concept is timeless, even if the exact categories and proportions will forever be a subject to ongoing examination and debate.

In both scenarios, what’s most important is that there is (1) a healthy balance, (2) a framework for making good, intentional choices, and (3) a useful check against simply defaulting to the part of the plate — or the type of interaction — that satisfies our craving in a given moment. Finally, as the saying goes, variety is the spice of life. Our experience is that the same is true when it comes to interactions between operators and investors — a little planning and a bit of balance / diversity leads to more efficient and effective interactions that are also just generally easier for everyone to swallow.

It’s easy for leaders to get caught up in the day-to-day of running small-scale businesses. Particularly during challenging times, it can take all our energy just to “keep the wheels on the bus.” Unfortunately, a casualty of operating in this mode is that we tend to focus far less on the long-term composition of the team — who’s actually on the bus, whether they are in the right seats, and who should be getting on / off at upcoming stops. This is hardly surprising — such planning demands both discipline and foresight. It’s also difficult to get right: organizational design is quite complex, and according to research from McKinsey & Company, less than 25% of organizational redesigns succeed. With that in mind, this post can’t begin to scratch the surface on this rich topic. Rather, it simply introduces a quick-and-dirty exercise to help leaders elevate and think proactively about their organizational “bus” both now and in the future. What follows is a description of the exercise (the “What”), some tips around its execution (the “How”), and some observations about its effectiveness (the “Why”).

The What: The exercise is quite simple and builds upon something that virtually every organization already has available in some format — a current org chart. Using that as a starting point, the leader creates a series of hypothetical future org charts for the business. Specifically, (s)he creates four new / additional org charts, each representing successive six-month intervals into the future. This results in a total of five prospective org charts, essentially five snap-shots that look forward two years, six-month at a time. The five org charts are as follows:

The How: This really is a simple exercise, so there is no need to overthink it. But a few pro-tips can’t hurt; and the following will help make the exercise even easier and more impactful:

The Why: The primary benefit of this exercise is hopefully clear: it is a low-effort way for a leader to plan out with intention and purpose how an organization will grow over time. It works well because it doesn’t require any special skills, resources, or training; and it is something leaders can easily do on their own a couple times of year with a moderate amount of discipline in a short period of time. A few of the side-benefits, and why this exercise works in achieving them, are outlined below:

In closing, this exercise is largely about interdependency between the business outcomes and the people-related aspects of organizations. Leaders generally have a keen sense from a mission and financial perspective of where they want their businesses to be at various points in the future. What we tend to be less good at is identifying and aligning the roles and skillsets necessary to achieve those objectives. Yet, they are completely interdependent — the envisioned goals, and the difficult-to-define team / structure required reach them. This exercise aims to help navigate the organizational side of things. Hopefully, it can help leaders develop a far-seeing view of who should be “on the bus”…and provide everyone a much smoother ride toward the desired destination.

There’s some debate about who first said, “Never waste the opportunity offered by a good crisis.” (N. Machiavelli, W. Churchill, R. Emmanuel). Whatever its origin, its meaning is clear: turbulent times lower collective resistance to change and provide a rare opportunity to challenge conventional wisdom. Unsurprisingly, this quote seems to have resurfaced frequently during these recent chaotic weeks; and its sentiment deserves some focused attention as it relates to small-scale software companies.

First things first: it’s hard to think of any crises that are actually “good.” The current COVID-19 pandemic is heartbreakingly awful in countless ways; and this post will not debate that. Neither will it focus on the specifics of the current crisis. Rather, this post is intended to support leaders looking to optimize this moment to bring both stability and positive change to their organizations…and to avoid mistakes that can make a bad situation worse. It does so by building on John Kotter’s 8 Step Process for Leading Change to help ensure that change initiatives are beneficial, successful and long-lasting.

What follows is the officially published “hook” and high-level summary for each of Kotter’s 8 steps for leading change, along with some brief situation-specific commentary from me. Please note: Any text in BOLD ITALICS is the exclusive work of John Kotter and the Kotter organization.

Amid the current crisis, Kotter’s steps for leading change appear as timeless and universally applicable as ever. And they seem particularly valuable for small-scale software businesses, given the existential threats start-ups face and the lightening-quick rate of change in their operating environment. In the midst of the current pandemic / economic crossfire, these steps offer some structure and security for those leaders looking to implement positive change and “make the most” of a decidedly challenging crisis.

The number one reason startups die is that they run out of cash. This is well known; and plenty of resources currently offer excellent advice for surviving turbulent times. But this is scary stuff with existential consequences for small-scale businesses; and guidance around cash-preservation can be overwhelming for company leaders. Having experienced challenging environments in 2001 and (even more so) 2008, I remember making the mistake of being trapped for days in forecast models or repeatedly scouring a laundry-list of line-items to be considered for cost-cutting. I was mired in the tactical weeds and later came to appreciate that some broader perspective would have helped guide my approach. The purpose of this post is to share a few lessons learned on this front and to offer some high-level frameworks to inform the thought process behind cash-conservation efforts.

I. Secondary Goals / Sacred Cows: Leaders intuitively understand the goal of cash-retention initiatives — to survive. It’s quite simple; just don’t run out of cash. But it is never that simple; and that is why it’s helpful for leadership teams to clearly set secondary goals for any expense-management initiative. This approach answers the question, “what is the NEXT most important objective of this effort (beyond simply staying solvent)?” For some companies, that may be safeguarding the customer experience and brand loyalty. For others, it could be maintaining the engagement / continuity of the entire team or retaining top talent. For more mature businesses, it might mean ensuring the business is positioned optimally for whenever the economy eventually turns around. Another way to arrive at similar clarity is by identifying “sacred cows” — those parts of the business where compromises will never be made. Whichever route is taken, this exercise helps leaders keep one eye — even in a crisis moment — on what is important for the longer-term health of the business.

II. If / Then / Then-by-When: The purpose of this mnemonic is to help leaders rise above the detail of expense-management and think beyond the tyranny of spreadsheets. It forces execs to go through a three-step business planning process, as follows:

In sum, this framework forces structure in what can otherwise become an ad hoc reaction to environmental challenges. It demands that company leaders a) thoughtfully envision potential scenarios, b) identify the qualitative and quantitative impact of those environmental forces on their business, and c) codify the steps and related timelines needed to address the challenge faced.

III. Assumptions, Decisions, and Control: Re-forecasts are inherently unsettling; and it can be difficult to know where to begin. One way to get a foothold is to separate where to make “assumptions” and where to make “decisions.” A general rule of thumb is to make assumptions about the top-line (sales / bookings and corresponding revenue) and make decisions around expense management. Why?

The truth is that companies ultimately cannot control whether clients actually buy from them; so, they need to make educated assumptions about customers’ buying behavior. Further, we’ve found it helpful to first focus on (and make the most pessimistic assumptions about) the types of revenues that companies least control. This generally means new sales to new customers, since they are the most speculative and rely most on customers making a proactive and incremental outlay of cash. Then, we move methodically down the risk ladder. The next most at-risk revenue class tends to be expansion sales to existing customers. Then come usage-related revenues. Finally, existing client renewals tend to be the most secure (but still ultimately at-risk!). When companies have great data, they can even further refine their renewal assumptions based on cohorts (products used, type or size of customer, and date of initial purchase). Breaking revenue streams out in this way allows companies to thoughtfully and granularly quantify risk to the top-line.

When (and only when) a company updates its top-line expectations, they can then begin to make informed decisions about expense-management — because they ultimately control expenses and can manage them accordingly. It’s helpful to sequence expense related decision-making opposite to that on the revenue side. Start with the expenses over which the company has the MOST near-term control and work the other way. This is because controllable costs offer the best ability to quickly aid in cash conservation. Highly controllable costs are almost always discretionary / un-committed, non-personnel expenses (e.g. marketing campaigns). Month-by-month subscriptions tend to come next. Consultants and contractors are also somewhat manageable (albeit not nearly as easy to pare back). Drastic measures such as “reductions in force” are far trickier still; and long-term leases (e.g. rent and pre-paid annual contracts) are often most challenging to derive savings from in the short-term. The following graphic from an excellent recent study by A&M (Alvarez and Marsal) concisely captures these dynamics and expands well-beyond.

A note about the elephant in the room: By far the most excruciating expense-related decisions revolve around personnel costs of the core team. Unfortunately, this is also the richest vein to mine from an expense management standpoint, because the majority of expenses in SaaS businesses are people related (yet again proving the adage that nothing valuable is ever easy). Moreover, the dynamics of personnel decisions are deeply complex and interdependent both financially and culturally; and leaders need to make choices in this area with the utmost consideration and care. This topic certainly warrants a more complete discussion but is not the focus of this particular post.

Okay, so…with these frameworks in the toolbox…what comes next? As is often the case when it comes to operational execution, it starts with communication. A range of diverse stakeholders will be involved in, and impacted by, any of the activities described above; so clear, effective communication is key. Although these decisions are made based on data and reason, their communication demands empathy and compassion — none of us wants to be the leader who gets stuck in spreadsheets(!). In a world where working at a physical distance is not just a choice, but a necessary health condition, such compassionate communications are more important ever.

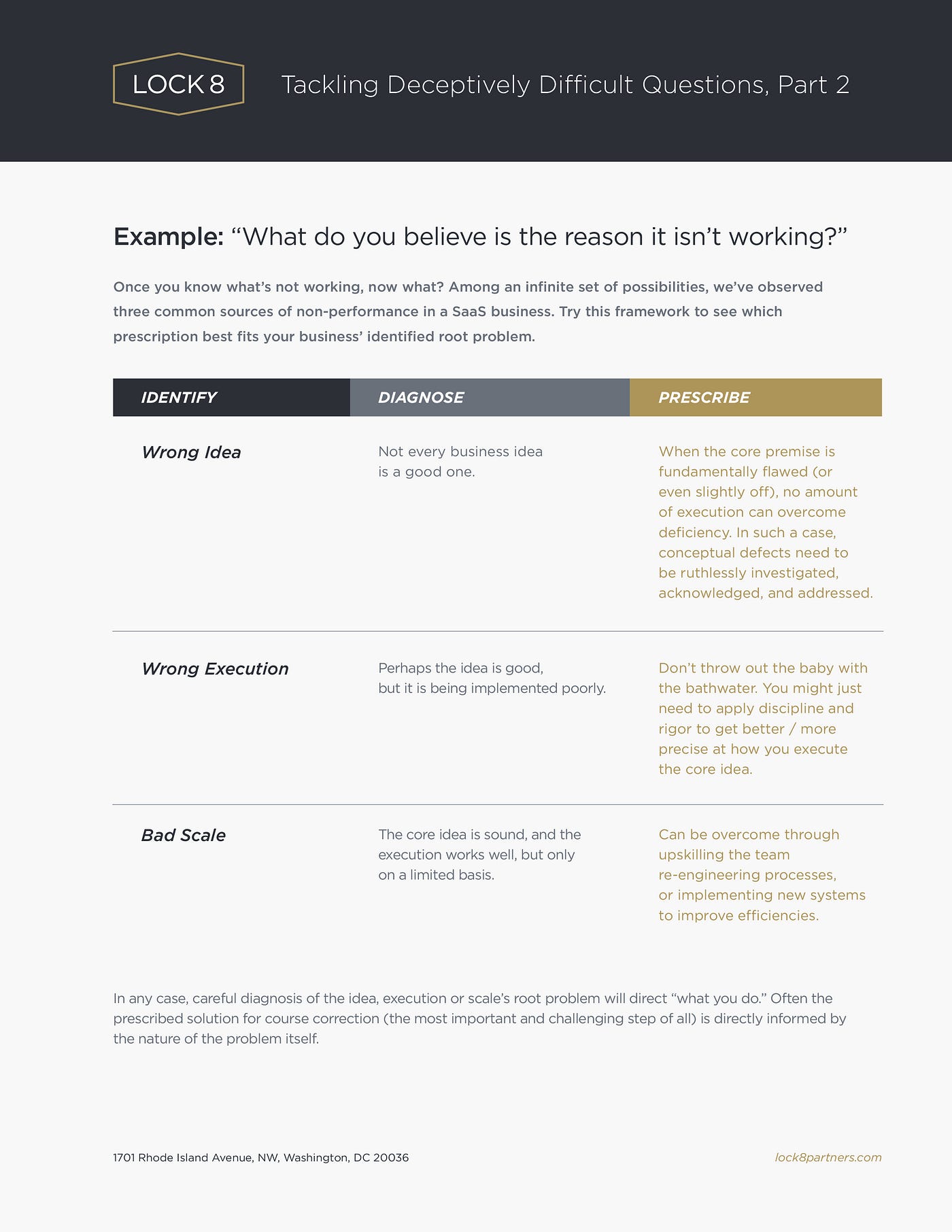

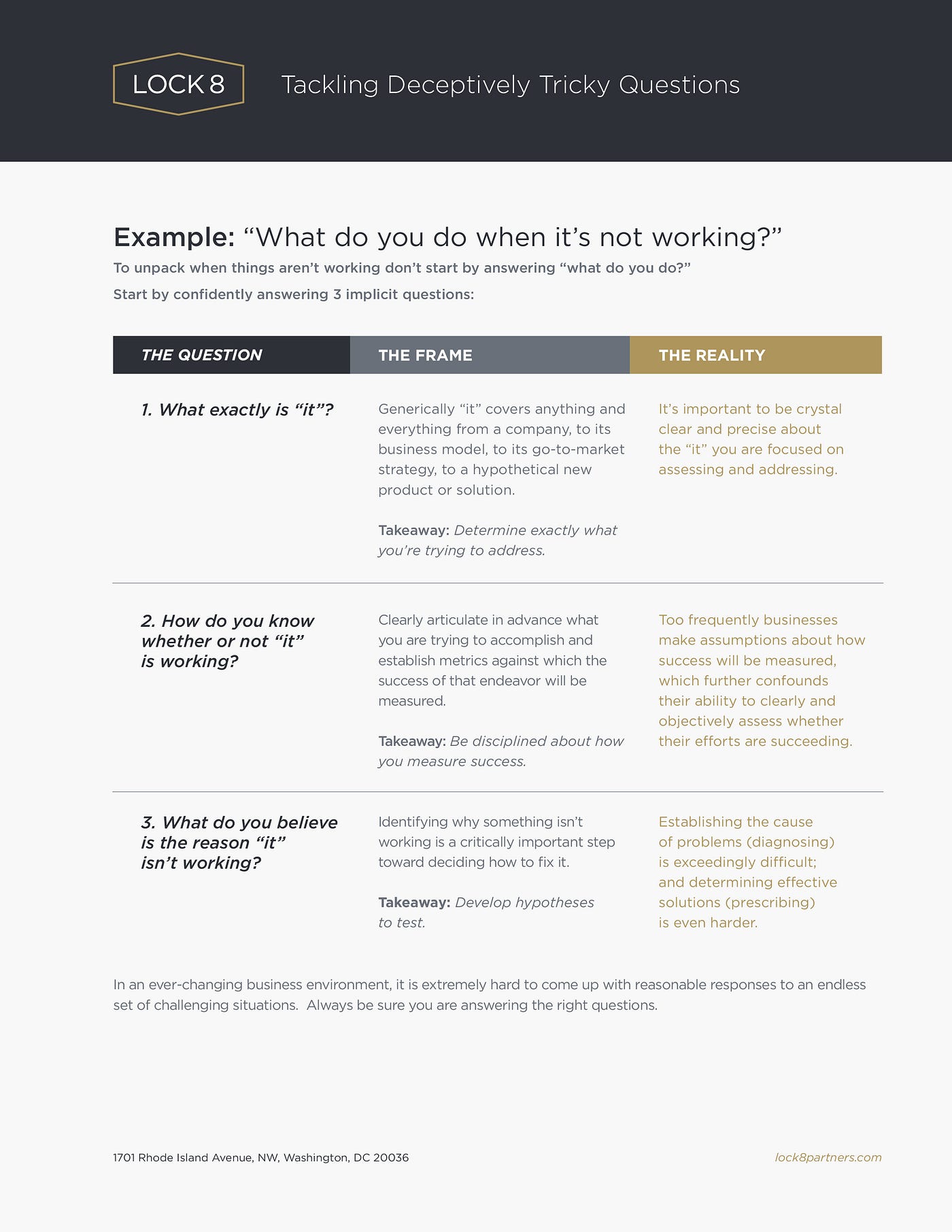

This blog recently featured a post that invoked the First Rule of Holes (“Stop Digging!”). That piece had been triggered by some business-planning discussions; and it advocated taking a structured approach when tackling deceptively difficult business questions. In that case, the seemingly innocuous question was “What do you do when it’s not working?” That post offered a framework to assist in the first step of problem-solving — actually identifying the existence of a problem in the first place.

This is part two of that post. It picks up where the last one left off: developing hypotheses to test why something isn’t working. Building on the initial framework, this piece endeavors to share a structure to use in the critical step of diagnosing the source of a business problem.

The “law of holes” was drilled into my head as a kid; and it is sound advice. The problem, of course, is proactively identifying whether and when you are actually digging yourself a hole.

I was recently reminded of this dynamic while visiting with the impressive leadership team of a 40-ish person SaaS company. We had met to discuss a range of topics relating to the life cycles of growing businesses. One person posed a seemingly straightforward question to the group that resulted in an immediate and spirited exchange: “What do you do when it’s not working?”

As a rich discussion unfolded, I remained silently stuck in the subtle, complexities of the question. While the debate whizzed past, I did what I often do when stranded in such situations — start to draw. The graphic below is a more formalized version of my notes and thought process from that session. It’s also an attempt to offer a simple approach to tackling this deceptively tricky question, and potentially others like it that prove surprisingly elusive to wrangle.

In a previous post, I shared observations relating to the process of re-platforming a SaaS solution. I was grateful when a former colleague reached out to comment on that piece. He offered that the term “SaaS” was somewhat limiting in this case, and that the principles in the post applied to any number of modern software delivery models. And, because no good deed goes unpunished, I asked him to guest-write an article that topic. Thankfully, he agreed! Chad Massie is highly qualified to opine on the issues encountered when deciding how to utilize cloud services while modernizing the architecture of a SaaS solution. I’m delighted to share his thoughts on this topic on Made Not Found. Thank you, Chad for the post that follows.

____________________________________________________________

For any business, but especially for those providing software as a service, cloud infrastructure offers a tremendous opportunity to drive organizational value. The question is not if a cloud strategy is appropriate, but rather which strategy to pursue and how to ensure that business and user value drive the decision-making. The five observations below were developed over five years of operating a high volume, high availability, cloud native software platform, and though there are several technical take-aways, the most important lessons are the human ones. Those observations and the related reflections on people and teams are below:

There is no single cloud strategy

In ways that can be both advantageous but also challenging, not every software or business will be best served by the same cloud strategy. This provides great flexibility in terms of timing and investment, but it also signifies that time spent up front posing the essential questions, understanding the needs and clearly defining the desired goals, and establishing the acceptable risk profile will pay considerable dividends (e.g., start with why).

The primary question of whether to “rehost” or “replatform” or “rearchitect” has no obvious answer. Each of these approaches has pros and cons — from a technical perspective, of course, but just as importantly from cultural, operational, and business value angles — and all can offer benefits for your organization. A rehosting strategy can help reduce near-term risk but might slow the upside value for an aging application; rearchitecture can provide a path for addressing major technical debt and modernizing the user experience but brings with it more significant complexity and change that may be more than your business or team is in a position to accommodate. Again, understanding your own context and priorities will help lead you to a better decision for your organization. You might determine that experimenting with an application that has a lower risk profile (e.g., an internal application, a non-mission critical platform) or a specific operation (e.g., disaster recovery) is the path that will ensure long term success, or you might determine that an all-in approach is the way to best serve your customers and inspire your staff.

Cloud is a culture (change)

Processes, organizational structure, and technical strategies that were foundational to success in an on-prem or hosted SaaS operation will not necessarily translate in a true cloud environment. The cloud requires a shift in cultural thinking, and as a result, demands a well-considered change management strategy for your team(s). One common theme is establishing a Devops mindset whereby the members of your various technical teams are involved in the full lifecycle of product delivery and support. Another is fostering an environment of knowledge-sharing and a blamefree ethos. The amount of new learning to be performed and the pace of change in cloud technologies require open communication, collaborative work, and “failing forward.” Further, the culture of learning and partnership requisite to success in the cloud extends beyond technical roles; product, marketing, finance, support, and management positions will all see implications to their work and their team interactions as a result of a cloud-oriented strategy. They must be incorporated into the transition planning and energized by the opportunities every bit as much as the technologists.

Patterns are your friend

Similar to the way software and user experience patterns have emerged over time, there exist many proven cloud architecture and process patterns that can help reduce effort and risk while ensuring security and operational reliability at scale. Whether incorporating elements of Amazon’s well architected framework, pillars of great Azure architecture, or Google’s cloud adoption framework — or something else — make use of these cloud patterns to shorten the time it takes to realize benefit for your organization. As with anything in life, though, an extreme position can limit our perspective, and cloud architecture is no different; it is both a science and an art. The scientific patterns and frameworks should be used to help streamline your architectural approach, but their parameters shouldn’t get in the way of your team’s creativity, the practice of experimentation, and applying their unique contextual knowledge in crafting the most valuable solutions for your business.

Instrument, monitor, and automate

Cloud infrastructure and the technologies that have been developed to support cloud-based software lend themselves extremely well to measurement and instrumentation. The fidelity of this information provides exceptional insight into the operations of your technical platform, in identifying issues proactively, and in understanding user behavior. Additionally, since utilization of a cloud infrastructure eliminates the dependence on physical hardware and enables access to on-demand scale, your strategy should push to automate as much as possible. Besides reducing repetitive efforts, automation will diminish the risk of human error and security exposure, increase overall quality, and help in delivering an optimal experience to your end consumers.

The cloud is constant innovation and reinvention

Advancing a cloud infrastructure strategy is an amazingly exciting journey. The dynamic nature of the landscape forces evolution and thoughtful change. As with any sound technology strategy, it demands attention to maintenance, performance, and reliability, but it also provides for reinvention and innovation in manners that did not exist previously, especially for small and medium sized software businesses. Rather than investing large amounts in original R&D, you could choose to utilize your cloud vendor/partner as your R&D arm, investing your resources in making the most of the innovative assets they bring to market while also providing enormous professional growth opportunities to your team. A cloud architecture gives you much more flexibility and a broader range of strategic options than has been historically available to SaaS companies, allowing you to select an approach that best meets the needs of your business, your team, and your customers.

Though the pathways toward a cloud architecture are now much more well-worn than they were several years ago, each software platform and each business is different. Coupled with the reality that cloud technology is a perpetually changing environment, there are no universal strategic approaches that will guarantee success. However, if you start with the right questions and understanding of the business drivers, build a work and communication plan aligned around strategic goals, and advance a team culture that values learning and collaboration, I believe the lessons above are applicable globally and can help ensure that your organization reaps a cloud strategy’s tremendous benefits.

With those fateful words, the meeting ends on seemingly solid ground. Unfortunately, too often a team’s commitment begins to erode almost immediately after adjourning. In these scenarios, a corrosive force is hard at work, devastating teams and laying waste to even the most solid plans. It’s called re-trading, and it takes place when someone(s) revisits a settled decision with the intent to change plans after the fact. This post attempts to shine a light on the toxic team behavior and offer some thoughts for combating it. But first let’s take a step back and offer some context:

“Disagree and commit” is a management principle which states that individuals are allowed to disagree while a decision is being made, but that once a decision has been made, everybody must commit to it. According to Wikipedia, this principle has been attributed to such icons as Andy Grove, Scott McNealy, and Jeff Bezos. Whatever its true origin, it “pinpoints when it is useful to have conflict and disagreement (early states of decision-making, but not after the decision is made). It is also helpful in avoiding the consensus trap, in which a lack of consensus leads to inaction.” In general, this principle is useful in organizations that value different perspectives but have finite resources to pursue seemingly unlimited ideas (i.e. in most growing SaaS businesses). It works well, so long as people commit in good faith to a plan and then maintain that commitment even in the face of inevitable adversity. It fails miserably when people’s commitment wavers and they seek to revisit the original decision via a re-trade. The re-trade can present itself in any number of different forms, including:

Whatever the precise form, re-trading reflects an unhealthy team dynamic. Interestingly, re-trading rarely takes place within the context of an open setting (i.e. a leadership team meeting), but rather often in 1-on-1 conversations behind closed doors. This is a useless waste of time. It sows the seeds of mistrust (what are they whispering about in there?). It creates factions and unproductive conflict. Even worse, these discussions often spill over beyond the attendees of the original meeting. In this way, leadership team members can dangerously undermine their peers, which completely freaks out the broader team (no one’s happy when the “adults” bring “the kids” into their fight). Needless to say, if these whisper-campaigns gain traction, they can completely derail the original agreed-upon plans. Left unchecked, these side conversations can also have a debilitating long-term effect on future decisions. Specifically, if people believe that they can re-visit decisions after the fact without negative consequences, then they may be incented to simply lay-low during initial debates and surreptitiously seek to get their way later-on. In short, once re-trading becomes normalized, no future decision will ever be safe from the threat of a re-trade.

On the contrary, in his classic book “The Five Dysfunctions of a Team,” Patrick Lencioni offers a succinct description of how truly cohesive teams behave:

Lencioni’s model also offers insights regarding ways to combat the re-trade. As I often say, there is no cure-all for human behavior. But if re-trading blooms in darkness, then sunshine is the best disinfectant. Specifically, pre-emptively calling out the dangers of re-trading goes a long way toward helping teams arm themselves against it. Unlike Voldemort in the Harry Potter series (“He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named”), openly acknowledging the potential for re-trading raises people’s awareness of and vigilance against it. Naming and shaming this behavior can give team members language to identify and resist peers’ efforts to engage in after-action 1-on-1 gripe sessions (a central means to waging a re-trading initiative). It also allows leaders to establish criteria for when it is appropriate to re-open past decisions. Specifically, facts and circumstances do change over time. And, if the realities on the ground justify it, then decisions absolutely should be reconsidered by the team. By establishing this as the one reason to re-open prior decisions, leaders can set a high bar for when / how / why plans can openly be re-litigated. Finally, because an ounce of prevention truly is worth a pound of cure, Lencioni’s model offers good guidance on how to address the root cause of re-trading. Maniacal focus on building trust and embracing unfiltered conflict early-on in decision-making processes will always be the best way to avoid downstream re-trading and all its devastating effects.

“So, we’re all in agreement, right? Great, let’s do it.”

We all want to prove our worth. We aspire to demonstrate competence, deliver value, and be recognized for our contributions to group goals. And this feeling is particularly acute for leaders during their early days in new roles with new organizations. From the moment they are introduced, new senior leaders are scrutinized by their management teams, by clients, by board members, and by many other stakeholders. Under these microscopes and carrying the weight of such expectations, executives are understandably eager to establish credibility and secure early wins.

In this environment, it’s also unsurprising that questions arise around the appropriate pace of leaders’ ramp-up time. Michael D. Watkins does an amazing job of tackling this complex issue in his book “The First 90 Days.” One of the useful concepts presented in that book is a leader’s “break-even point,” which is illustrated below:

Source: “The First 90 Days: Proven Strategies for Getting Up to Speed Smarter and Faster,” Michael D. Watkins, Harvard Business Review Press

Watkins points out that, although the timing to reach the break-even point can vary based on numerous factors, the goal is the same for virtually all leaders: “to get there as quickly and effectively as possible.”

But rushing things exposes risks and traps that can lead to what Watkins calls “vicious cycles of transitions.” These cycles are characterized by an interconnected set of (a) inadequate learning by an executive, (b) ineffective relationship building, (c) lack of supportive alliances, (d) bad decisions, (e) lost credibility, and (f) organizational resistance. In sum, these cycles can kill any new leader’s plans for success. “The First 90 Days” combats these vicious cycles with a broad range of practical strategies for managing transitions with purpose and precision; and I recommend this book to anyone contemplating any new leadership challenge.

This post targets one aspect of this broad topic. It introduces a specific discipline that we’ve found to be consistently helpful in small-scale businesses in not only avoiding these vicious cycles, but also in accelerating leaders’ journey to the break-even point and beyond. It’s an astonishingly straightforward concept with impressive outcomes; but it can be challenging to execute in a leader’s busy days in a new role: The discipline is LISTENING TO PEOPLE. It is unquestionably simple; but the devil is in the details. Below is a quick explanation of the process, along with some tips and observations about why it works.

This approach centers around harnessing the power and value that comes from 1-on-1 interactions between people. It relies on a leader authentically engaging in individual conversations with every member of a team. As I wrote about here, it also demands that the leader clearly demonstrates his / her willingness to hear even inconvenient truths, and to create a safe environment for people to share their candid views. Note: while this practice would likely be infeasible beyond a certain scale, we’ve used it effectively in teams as large as 100. At the highest level, the process entails three key steps:

An important remaining item still to cover is: what are the actual interview questions? Although these certainly deserve flexibility and can vary by business, we’ve had success with a few intentionally open-ended and precisely worded questions. These have been revised over time, and each is included for specific reasons. Those questions and related commentary are below:

Getting up to speed quickly and intelligently is a critical, recurring skill for all new leaders. It is our hope at Lock 8 that this framework will assist leaders on this high-stakes, high-reward, highly-complex journey to the break-even point and beyond.