This blog has focused extensively in the past on the topic of first-time CEOs within small-scall SaaS business. This post made the case for hiring first time CEOs; this piece shared tips for screening / selecting those CEOs and how to support their transition to chief executive; and this one offered tactics around leveraging formal appraisals to optimize CEOs’ performance. The following 2-part post aims to pick up where those others left off. Specifically, it addresses CEO performance and how to thoughtfully assess and enhance it. We’ll tackle this topic in two parts.

1. Part I introduces a framework that summarizes for aspiring CEOs the seemingly infinite demands that chief executives face. The purpose of this bit is to help CEOs clearly understand “what good looks like” in terms of performing this critical role on behalf of their organizations.

2. Part II shares how Lock 8 Partners leverages this framework in conjunction with other artifacts to help our portfolio CEOs develop and perform. Part II is directed toward board members or anyone seeking to bring out the best in CEOs — by both holding CEOs accountable and prioritizing their professional development.

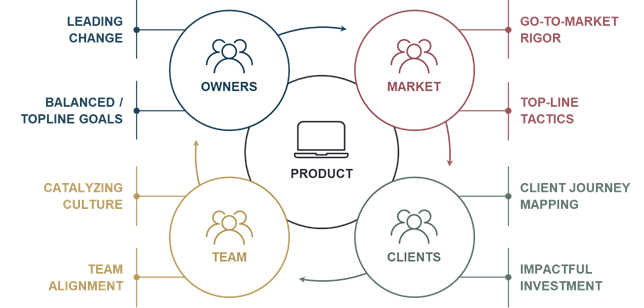

What follows is text pulled from an artifact we call the CEO Developmental Rubric (CDR). It is one of the frameworks we use to evaluate and provide feedback to CEOs. The CDR seeks to dispel whatever pre-conceptions incoming first-time CEOs may have about their new role…and to clearly outline precisely what is expected of them in that seat. Those expectations span eight core disciplines, each with supporting themes and explanations. Below are those disciplines / themes / summaries:

Leadership: Build Leadership Team / empower individual contributors / practice self-reliance / foster culture of learning, growth, & performance / plan for future-state

The CEO surrounds themselves with high-caliber LT members and actively works to foster cohesion / collaboration / independence / inter-reliability among this “First Team.” In turn, the CEO and LT recruit / develop / empower individual contributors that strengthen the team and advance attainment of company goals. The CEO lives and models the company values and establishes a culture and environment where others feel safe and motivated to do the same. The CEO proactively considers the org’s future-state and engages in succession planning to maximize org effectiveness and minimize the impact of transitions or organizational surprises. Finally, L8 CEOs strike a balance between developing the team and / but also being self-reliant — they are long-term builders, but also action-ready doers…and they are comfortable rolling-up their sleeves to get things done individually and alongside their teams.

Vision and Strategy: Articulate Vision / lay-out Strategy and Tactics / consider and mitigate complexities / inspect & adapt

The CEO articulates and codifies a clear, concise, compelling Vision for the company and where it is going…and shares that effectively with stakeholders, particularly the internal team. The CEO lays out specific Strategies and Tactics by which the company can successfully execute that Vision and achieve well-defined / broadly understood Objectives. The CEO considers the deep complexities of these tasks amid the dynamic / nuanced competitive environment in which the company operates. The CEO remains steadfast on the Vision but regularly reconsiders / re-calibrates / adjusts Strategy & Tactics in a timely manner to an ever-changing operating landscape.

Execution / Resource Management: Hit the Plan(!) / enforce operating cadence / optimize team time / focus on priorities & avoid distractions

Through discipline and rigor, the CEO ensures that the business just “gets things done.” Specifically, the company can be counted on to consistently attain its stated Company Objectives (Hit the Plan!). The CEO establishes organizational focus on these Objectives and implements an operating cadence of daily / weekly / monthly / quarterly / annual activities that optimizes the business’ most precious resource — people’s time. The CEO prioritizes the most impactful initiatives and ensures that others do the same. The CEO avoids distractions or endeavors that detract from the company’s resources and ability to get things done — both in the immediate and longer terms.

Communications: Communicate with intentionality / balance views / listen relentlessly / seek coaching & incorporate feedback

The CEO communicates with purpose and ensures that the organization does likewise. The CEO communicates intentionally and proactively with all stakeholders in form / tone / substance / frequency / altitude that is targeted and specific to each audience (those being: Market / Clients / Team / Shareholders / Options Holders). The CEO communicates credibly with the board of directors (BoD) in a way that fosters BoD engagement and impactful discussions. The CEO calibrates communications to ensure a realistic view and one that balances optimism / pessimism and that avoids “hope as a strategy” in favor of “confronting the brutal truth.” The CEO receives communications at least as well as they transmit. The CEO actively listens to all stakeholders, seeking always to learn new perspectives that can benefit the business and themselves. The CEO seeks / accepts / incorporates feedback from a broad range of stakeholders and proactively closes the loop on suggested points to explore.

Analysis: Leverage data / generate insights / build instrumentation / focus pragmatically

The CEO leverages available information to inform a thoughtful, fact-based, data-supported view of the situation and opportunity. The CEO synthesizes data to formulate second-order insights and hypotheses regarding where the business needs to go. The CEO takes a long-term view toward instrumentation, with a “patient-but-ambitious” understanding that small-scale SaaS businesses frequently need to build systems and processes from the ground-up and over time to support the desired-state of business analytics. The CEO is pragmatic in terms of ruthlessly focusing on metrics-that-matter and avoiding the “noise vs. signal” problem of looking at too many metrics that overwhelm business leaders and under-impact the business. This same principle applies to frequency of metrics review — the CEO regularly examines metrics but avoids “living in the numbers” at the expense of seeing the big picture for the business or engaging authentically with others.

Learner / Owner Mindset: Approach issues openly / commit to CEO craft / seek broad understanding / spend like an owner

The CEO consistently demonstrates two important, and somewhat contradictory, mindsets — that of the “Learner” and the “Owner.” The CEO assumes a Beginners Mind, approaching issues with genuine curiosity, openness, and commitment to learning. The CEO brings a strong appetite for advancing their craft of becoming the best leader / CEO they can be. The CEO also behaves like an owner of the business — seeking to understand all aspects of it, but with a healthy appreciation that they cannot possibly be / do all things. The CEO also acts as the owner in terms of financial stewardship. They treat / spend company resources with prudence / frugality, but also with a willingness to invest and take calculated risks to optimize long-term value of the enterprise.

Resilience: Confront the brutal facts / remain focused / ruthlessly compartmentalize / maintain your humanity

Being the CEO of a small-scale SaaS business is hard. Very hard. There is always more to do, and almost never enough resources to do it. The CEO is frequently confronted with new, often unpredictable crises, for which there is rarely infrastructure or a roadmap to assist the CEO in navigating. For these and so many more reasons, the CEO must remain resilient, unflappable, unsinkable. They must consistently demonstrate what is commonly referred to as “grit.” And they need to channel this type of resilience into the DNA of their organization. All of this must be accomplished while maintaining credibility among the team and demonstrating empathy, so as not to be perceived as overly rigid or unsympathetic to the challenges the team collectively faces.

Creativity / X-Factor: Innovative ideas / ideas into action / action into advantage / advantage into value

The CEO brings something extra to the business — innovative product ideas, contrarian vision for the industry, best-in-class domain expertise, innovative solutions to process challenges, ground-breaking ways to optimize resources, highly differentiated ways to position / sell the company versus competition — anything that creatively provides the business with a difficult-to-replicate advantage. This X-Factor can take countless forms, and it can be the difference between good versus great businesses and for strong versus exceptional leaders.

Although the responsibilities of CEOs truly are overwhelming, we’ve found that these eight disciplines encapsulate what we at Lock 8 hope CEOs will bring to the SaaS businesses in which we invest. I’ll go into more detail in Part II of this post on the mechanics of how these concepts get applied. But hopefully they stand on their own as a focus-producing resource for aspiring, first-time, or even veteran CEOs.

More Tools for New CEOs (1 of 2) was originally published in Made Not Found on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

A prior post on this blog referenced the use of formal assessments as a vehicle to support first time CEOs. I have admittedly received pushback in the past on this point from experienced CEO-pals who question the value of such instruments. Fair enough; to each their own. But I stand by that position and offer this post in an effort to support it. This piece will double-click into three questions relating Lock 8 Partners’ use of diagnostic tools for execs:

I. What is the general thinking behind using formal appraisals with execs?

II. Which specific tests do we use and why?

III. How do we administer and use the assessments for optimal impact?

The goal here is to share some lessons learned in order to help others optimally position CEOs / execs for success in their leadership roles.

I. General Thinking:

Leadership is critical to organizational performance, and CEOs / execs are key drivers of company success. Likewise, CEO roles — even in small businesses — are enormously complex, with many potential variables ultimately influencing outcomes. At Lock 8, we naturally want to leverage any available resource to help CEOs succeed, particularly the first-time CEOs whom we prioritize hiring.

To be clear, our objective with these assessments is not to weed out the “smart” from the “astonishingly smart” — that’s not what we believe matters most to small-scale SaaS businesses. Rather, we are trying to understand how execs align to a specific role in two main areas: (1) personality factors and (2) problem solving. To do this, it is first necessary to have an in-depth understanding of the particular business and nuances of that particular executive role. Only with that context are we then able to use these two types of information to understand how someone aligns to a given role, builds relationships, performs under pressure, processes information, and makes sound decisions. If an assessment can offer an advantage to our CEOs in this fascinating and high-stakes puzzle, then sign us up for these tests…

II. Which Test(s):

…but, not just any test, and certainly never only one test. The CEO role and the individuals who successfully navigate those roles are simply too complex to rely on any one measure to predict success. It would be the equivalent of saying “choose one thing that makes all CEOs successful” — it just doesn’t exist. Rather, such a multi-faceted endeavor warrants using several different tools, measures, and techniques. Following expert guidance, we have oriented around four tests, with two focused on each of (1) personality factors and (2) problem solving.

Personality Factors: Personality factors speak to the types of preferences and inclinations that determine how a person is likely to behave under normal circumstances, as well as when under pressure. We use two instruments to measure these different aspects of personality; they are the Hogan Personality Inventory (HPI) and the Hogan Development Survey (HDS).

The HPI is a measure of “normal personality” that provides the following:

The HDS identifies the following:

The HPI and HDS provide a more in-depth understanding of the preferences and thinking that drives what many refer to as “Emotional Intelligence” (EI) or “Emotional Quotient” (EQ). They also facilitate a very quick / early understanding of an exec’s communication style, in order to better inform how that person could interact with a team. Research consistently shows that leaders who have higher self-awareness regarding their strengths, opportunities for growth, and biases to behave in certain ways are more likely to be successful. They often build stronger, more mutually respectful relationships with a broader range of people; and this increases the probability of being able to address highly complex issues effectively. For these reasons, we pay close attention to HPI and HDS.

Problem Solving: But it isn’t all just touchy-feely. Problem solving and critical thinking skills are foundational in considering whether or not someone has the capacity to serve in a leadership role such as CEO. This is where the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal II (W-G) and the Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM) come into play.

The W-G helps us measure the following:

The insights gained from the W-G involve whether an individual can process highly complex information efficiently and make strategic decisions that take into account both short- and long-term consequences. However, the situation and the data regarding it are often ambiguous or incomplete; and this is where the RAPM is useful.

The RAPM helps us accomplish the following:

Combined, these two measures shed light on an individual’s ability to do the “systems thinking” or to “see the bigger strategic picture” that successful CEOs must have. In addition, they allow a CEO to prioritize issues and direct time and resources to those most critical concerns in a timely manner.

III. How To: Handle with Care

Given these robust, valid measures of both critical thinking and key personality factors, the question becomes how these assessments should be administered, used, and shared. The honest answer is: with flexibility, care, and compassion. That said, below are the core takeaways from our experience:

In closing: I’d like to thank Dr. Gary Lambert of Q4 Psychological Associates, not only for his significant contributions to this post, but also for his generosity of spirit in the sharing of his expertise and experience. Gary has been a great collaborator in Lock 8’s efforts to consistently improve our ability to set executives up for success. Beyond all of that, Gary is a pleasure and a lot of fun to work with.

A prior post made the case in favor of hiring first time CEOs to lead small-scale SaaS businesses; and this piece picks up where that one left off. Specifically, it expands on characteristics to prioritize when screening CEO candidates, some questions to help assess them, and — most importantly — ways to support executives in deepening those attributes once they are in-seat as CEOs.

Per that earlier post, “We prioritize candidates with high levels of humility / coachability, EQ (emotional quotient), systems-thinking, and prioritization skills; and the odds of their success are greatly improved by supporting them in an intentional, structured, and consistent way.

These supporting activities are critical: it is perfectly reasonable to ask rookie CEOs to lead effectively; but it would be naïve to ask them to do so without a support network or a shared commitment to their ongoing development. This post shares what that support can look like in practice by diving into “what / why / how” behind these particular characteristics and how fostering them can help position CEOs for success.

I. Humility / Coachability

II. Emotional Quotient

III. Systems Thinking

IV. Prioritization Skills

In sum, these characteristics are critical to help first time CEOs survive. And, while we certainly test for them in the interview process, we spend a lot more time and energy in helping to support the ongoing development of those attributes in CEOs over time.

A quick closing aside: these characteristics are crucial as CEO differentiators; separating the good from very good. They are “spices” that makes the meal compelling and something of unique value. The “main dish,” though, is comprised of a core set of must-haves that were summarized in a prior post as an exec’s ability to (1) Get it, (2) Want it, and (3) Capacity to do it. This latest post does not intend to suggest ignoring or in any way under-valuing such must-haves. Admittedly, without these staples, those spices would be wasted and without substance.

Last week I had the opportunity to speak with three different SaaS execs about their careers. Each had valuable experience within high-growth software businesses. Each brought deep management and functional experience, having led critical departments within their respective companies. Each presented themselves as personable, passionate, and articulate about their work. And yet, they were all grappling with how to take the desired next step of their career journeys — to land the CEO gig at a growing SaaS business.

These folks are not alone; countless aspiring leaders struggle to make this leap. This is unsurprising: although many executives harbor the lifelong dream of leading a company, the chief executive role is uniquely challenging; and the sheer numbers are stacked against elevating to this level. Likewise, seemingly everyone wants to get in on SaaS these days, making the odds even longer for would-be tech leaders. And yet, making the jump to SaaS CEO is far harder than it should be. In fact, like many things in life (such as college admissions, securing student internships, earning a roster spot on competitive teams), the “right to enter” can be even more prohibitive than the required qualifications to succeed. Why is that?! This post aims to identify, and hopefully poke a few holes in, some of the less obvious reasons for why it is so hard to navigate the path to becoming a SaaS CEO.

The Founders Path: The surest path to becoming CEO of a SaaS business is to start one. Again, this is unsurprising: founders are the natural choice to lead the entrepreneurial endeavors they initiate. After all, who better to rear the brainchild than the person who hatched the idea in the first place? This founder-as-CEO model has been reinforced for decades in our minds by the many well-known and truly remarkable individuals who have not only started successful businesses, but also subsequently led them through extended periods of growth. Thomas Edison, Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, Jack Ma, Payal Kadakia, and countless others have made this extraordinary achievement seem almost commonplace — it’s not. It is rare and amazing, and it should be celebrated as such. And yet, founders often remain CEO of their business until either (a) the business goes belly-up (bad outcome, but statistically the likeliest), or (b) the business succeeds and grows to the point of needing a hired-gun executive (good outcome, but often an emotionally fraught one).

This whole dynamic can be cruelly ironic in a couple ways. First, a fair portion of founders end-up learning that have little appetite for many of the CEO’s duties (such as: leading people, managing a board, exec selling, or sweating the financials). Rather, founders often prefer to start things…not finish them. Conversely, many executives yearn for the top-spot in a company and have invested heavily in developing related skills…but simply don’t possess the founder-gene. Consequently, one of the most viable paths to becoming a SaaS chief executive is blocked to countless qualified leaders simply because they “don’t have a great idea for starting a business.” As a short aside, many would-be CEO’s do end up choosing to start businesses, at least in part as an entrée into the corner office. Although this absolutely can work out well, it is generally a “tail-wagging-the-dog-ish” bad idea. Anyway…where exactly does this leave the non-founder SaaS exec who has the itch to prove herself in the CEO role?

Which Came First? For non-founders, the obvious route to “CEO-dom” is to work one’s way up the ranks. Unfortunately, this is also a narrow path with many pitfalls, including the fact that climbing the corporate ladder can take years or decades (with plenty of brain-damage and no guarantees along the way). To further complicate matters, not many employers actively recruit non-founder, first-time CEO’s. Traditional VC / PE investors, who often are responsible for hiring SaaS CEO’s, rarely (if ever) actively seek out rookie CEO’s. Again, hardly surprising: these financial stakeholders have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize returns while minimizing risk. Accordingly, very few are keen to take a chance on an unproven executive in the one role that will arguably have the greatest impact on the outcome of a given investment. Likewise, self-aware founders seeking to replace themselves generally tend to prioritize a proven track-record when considering their successors — and certainly not less-experienced first time CEO candidates! All of which begs the question: if one needs to have already been a CEO to become a CEO…how does one initially break-in? That is precisely the vexing chicken-and-egg problem that the executives described above are striving to crack.

The hard truth is that — like so many things in life (e.g. skydiving, performing in a live production, asking someone out on a date) — no training can adequately prepare CEO’s for the real thing. Sure, aspiring CEO’s could / should strengthen their CV by amassing increasing levels of leadership experience and developing valuable functional expertise. Sales, marketing, finance, and product management are all proving grounds for future chief executives. General management roles, particularly ones with accompanying P&L responsibility, are also “as good as it gets” in terms of prepping future SaaS CEO’s for the stress and complexity of “sitting in the big chair.” But even with such undeniable preparation, the first-time CEO remains about as appealing as an understudy on Broadway — highly suspect unless and until he / she demonstrates the ability to handle the moment and shine when the lights come up. These and other forces combine to create a stacked deck against aspiring CEO’s. But this doesn’t have to be the case.

Contrarian Closing: Why we like first-time CEO’s

With respect to all of the points above, we beg to differ. When it comes to early-stage SaaS businesses, we dig first-time CEO’s. While there are many undeniable benefits of prior CEO experience, there is also a lot to like about first-time CEO’s in this environment. First, they tend to be quite energized by the opportunity to “make something their own.” This typically translates into a high “want-to” factor, the importance of which simply can’t be overstated (as outlined here). This is particularly true when a leader marries that enthusiasm with a high-level of capacity / competence, which is overwhelmingly characteristic of anyone who is a legitimate CEO candidate. As another short aside, this point reminds me of this gem from Simon Sinek…so, so true). First-timers also tend to have a healthy respect for the complexity of the role / situation into which they are stepping. This encourages them to be open-minded and coachable; and it discourages them from prescribing before diagnosing. This is a crucial point; some of the biggest mistakes leaders make can result from defaulting to the assumption that they’ve already “seen this movie” (aka: fully understand a situation, before having completed exhaustive discovery). Rookies, on the other hand, rarely fall into this trap. Finally, sub-scale SaaS businesses tend to be scrappy and under-resourced; and first-time CEO’s can easily jump-in with both feet. Specifically, they are in a great position to leverage up-to-date expertise that draws on their functional background…and, in the process, to help the business punch well above its weight.

In fairness, not all departmental / functional leaders can successfully make the leap to CEO. We prioritize candidates with high-levels of humility / coachability, EQ (emotional quotient), systems-thinking, and prioritization skills; and the odds of their success are greatly improved by supporting them in an intentional, structured, and consistent way (both of which seem like topics for future posts).

In sum, though, up-and-coming execs can offer a great option as CEO’s of sub-scale SaaS businesses…much more so than is suggested by the narrow paths available for them to get there.

The CEO role can be described in countless ways. One definition comes from the Corporate Finance Institute, which states: “The CEO is responsible for the overall success of a business entity or other organization and for making top-level managerial decisions.” Accompanying that description is a list of the CEO’s roles and responsibilities, which is peppered with dynamic verbs such as: leading (X), creating (Y), communicating (Z), ensuring, evaluating, and assessing. Such a high-powered portrait of the CEO is unsurprising, especially given the commonly held notion that “real” CEOs should courageously lead from the front. And although Jim Collins’ classic book Good to Great introduced us to Level 5 leaders who are characterized as humble and reserved, the image of CEOs as vibrant action-heroes-in-board-rooms is a persistent and alluring one.

It is with all of this as context, that I was surprised in a recent board meeting when a CEO characterized his role in an entirely different way: as Chief Conversation Officer. “If you can create good conversations,” he offered, “You can create good outcomes.” This initially struck me as being a far more passive role-assessment than I’d expect to hear from an actual CEO. But, with its unwavering focus on delivering results (which is undeniably the responsibility of CEOs), this description resonated with me as being worthy of serious consideration.

Upon further reflection, I view this as an accurate and valuable addition to the responsibilities of the CEO. It is undeniably important for CEOs to foster effective discussions among a broad range of stakeholders. They need to create open dialogue with prospective customers in order to gain an informed understanding of jobs to be done. It’s imperative to cultivate candid conversations with existing clients in order to consistently improve products, inform future investments, address service issues, and avoid churn. A balanced and candid exchange with team members is crucial to enable them to perform, and to identify what obstacles stand in their way personally and professionally. And, finally, open dialogue with owners / investors is needed to align expectations and leverage their helpful perspective from above the fray of day-to-day operations.

Being a good conversationalist takes work; and not every CEO is naturally gifted in this area. Rather, the art of conversation is the subject of countless studies and far exceeds the scope of this post. But, as this previous post highlights, a bit of structure and a few simple practices can help CEOs up their game in terms of fostering effective conversations with consistency and intentionality:

This whole topic of CEOs as Chief Conversation Officers reminds me of the well known African proverb: If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” In today’s business environment where speed is rewarded, CEOs are wise to also remember to focus on going far, together. And that if you are going to travel far, it is always better to have good conversations along the way.

As SaaS businesses scale-up, one of the most important responsibilities of an executive is to participate in and support sales efforts to prospective new clients. New client sales are critical to the health of any early SaaS business, and senior executives can play a major role in helping sales teams attract customers. For many leaders, this is an entirely natural act which they execute with ease; for others it can be an uncomfortable stretch. In either case, their involvement needs to balance two competing goals: (1) help win business today that results in successful, profitable, long-standing customers, and (2) build the team’s ability to win more and more of these types of deals in the future. This second goal sometimes gets lost in the shuffle; and it significantly complicates how thoughtful executives engage.

Nearly two decades in SaaS leadership roles have taught me many lessons around an executive’s role in sales meetings (and contributed significantly to my hair-loss early in that period). As I think about those lessons, a majority tend to fall into three general buckets: two “Do’s” and one “Don’t,” as follows:

In closing, executives have a huge role to play in supporting sales efforts as businesses scale; and it can be difficult to balance the desire to help win deals today while building the team’s ability to win consistently in the future. Hopefully these few rules of thumb help leaders land on the stepping stones and avoid some of the stumbling blocks.

Being a first-time CEO poses many new challenges, and one of the trickiest can be interfacing with a board of directors. Perceptive executives quickly realize that boards hold hiring-and-firing responsibility over them; and boards clearly have significant influence over the fate of any business. With that in mind, it’s no surprise that prudent CEOs focus on carefully fostering board relationships. Unfortunately, this very inclination toward care-taking can sometimes backfire and lead to costly mismanagement of the board. Beginning with my first CEO gig in 2007, I’ve made my share of mistakes on this front, a few of which are outlined below…along with a lesson learned that should guide all of a CEO’s board interactions:

Admittedly, getting these items just right is a learned skill that requires a lot of error-filled practice. But one realization has proven to be consistently helpful in keeping on track: The CEO’s primary job is to engage the board. Specifically, the CEO needs to enable board members to share their significant experience, learnings, and pattern-recognition to the benefit of the business. The CEO should give board members timely, accurate, relevant information…and then shut-up and listen. That’s it. If the CEO fosters robust, honest, unrestrained, challenging discussion among board members, everyone in the business benefits. So, forget about the pretty slides; and focus on getting the board to engage with unrelenting candor. It’ll be the best use of everyone’s time and worth every minute of investment.