It is a good thing to be “coachable,” meaning capable of being easily taught and trained to do something better. It’s easy to understand why companies consistently seek to hire and reward coachable behavior in their teams. Based on this definition, I’d argue we all want to be coachable. Unfortunately, our egos often get in the way. This likely explains the countless books and articles that provide tips on how to become more coachable. These serve a valuable purpose; and I don’t have a beef with any of them. With one exception: their guidance seems to overwhelmingly focus on junior level professionals, and to largely ignore senior executives. At Lock 8, we strongly believe in the power of coaching to elevate the performance of executives and (correspondingly) the businesses they lead. This post shares some experiences and observations around coaching / coachability for people who need it just as much as anyone — seasoned senior leaders of small-scale businesses.

Contrary to popular belief, the need for coaching does not decrease as one’s proficiency / expertise / seniority increases. Elite performers of all types (e.g. athletes, performing artists, authors, painters, etc.) all tend to utilize more coaching, not less, as they advance in their respective fields. Want evidence: have you noticed the sideline of a big-time football game in recent years?

And yet, an anecdotal sampling of articles about coachability in the workplace shows an overwhelming focus on the most basic aspects of the topic. One recent article from a highly respected publication offered five tips for being more coachable — and all five of them focused on responding well to feedback. Although requesting / receiving feedback is an undeniably valuable skill, I’d argue it is a necessary, but insufficient condition to being coachable. For executives aspiring to become more coachable as their careers progress, simply getting better about asking for feedback won’t move the needle.

This all has been top-of-mind for me lately: I recently resumed working with an executive coach, after a six-year hiatus from doing so on a formal and consistent basis. The experience has been really positive. And it has been a reminder that there are wide variations in these coaching sessions, with some being truly groundbreaking and others not so much. Reflecting on this, I’ve realized that the variations are largely of my own making. Certain behaviors elevate the results, while others undermine my efforts to be coached. In short, the outcome depends on how “coachable” I’ve been in connection to a particular session. Below are some observations around my recent exec coaching experience, in hopes that they will help other execs who are looking to optimize their own coachability.

To finish where we started, we all want to be coachable. Like anything worthwhile, it takes hard work and some intentionality to make material improvement. Meanwhile, I’ve been enjoying working out the kinks as I’ve re-entered the world of working with an executive coach. And it really is worth the effort. As we say at Lock 8 all the time: coaching’s impact effects not only the person receiving the coaching, but also the team they lead and the organizations they drive.

A previous post on this blog shared observations about high-stakes SaaS product development initiatives; and a follow-on piece took a deeper dive into setting related cloud services strategies. Together they focused on considerations when undertaking major SaaS product initiatives (such as re-platforming projects, new user interface introductions, infrastructure changes, functionality expansions, code re-writes, and others).

Although this post builds on those prior pieces, it steps away from the product side of things. Instead, it examines a wide range of critical, but often overlooked, “other stuff” needed to successfully introduce meaningful product changes to customers. Borrowing from the world of project management, we’ll broadly call this topic operational readiness. The harsh reality is that even a well-executed product development initiative can be greatly undermined by inadequate operational readiness. And this is often where many SaaS companies falter, particularly small-scale businesses without mature systems and processes. With that in mind, here are ten quick lessons learned and five “non-product” questions / exercises that can help organizations manage major product change initiatives.

LESSONS LEARNED:

QUESTIONS / EXERCISES:

1. What are our “big rocks” of operational readiness?

This deceptively simple question forces companies to consider all the aspects of their offering that directly or indirectly impact how customers experience their software solution. Although there is a wide range, just a few of the usual suspects on this list include:

2. Who benefits from this project and how so?

Again, this one seems simple but warrants focused attention. The truth is that big product initiatives can take on a life of their own and cloud our understanding of their true purpose and benefit. It helps to think of each stakeholder group (e.g. customers, prospects, partners, internal team members, financial stakeholders) and even sub-sets of users (admins, super-users, casual users, executives). Then, lay-out the tangible benefit each group will derive from the initiative. These might include: a shorter learning-curve (for customers), ease of support or ability to code more efficiently (internal team), or less resource intensive implementation cycle (multiple beneficiaries, including financial stakeholders). We better have good answers for each stakeholder, or else it is going to be hard to justify to them the inevitable cost / effort it will require to adopt the proposed changes (aka: the “pain-of-change”).

3. What are the situation-specific complexities to consider?

Complexities reflect the unique nuances of each product and user-base. These are the characteristics of your business that will largely define how the company must prepare to support impending product changes. Examples of these include:

4. What are the guiding principles to be upheld?

Like any set of principles, these should represent the “non-negotiable” commitments. These may be commitments to customers or to your own organization; and they may be tacit or openly communicated. In any case, what is most important is that they are not open to compromise. Some hypothetical examples of these might be:

5. What are the operating decisions to be made?

All of the questions / considerations above play a role in organizational readiness; and companies must ask and answer a number of pragmatic questions. A few of the usual suspects tend to be:

In sum, change is hard. Operational readiness, when painstakingly undertaken and executed by a company, goes a long way toward easing that pain for its clients. Failure to do so, however, can result in tenfold the pain downstream for everyone involved.

People say it all the time, usually with great pride: “We are a sales-led company.” Or, in businesses with deep technical roots, it might shape-shift into: “We’ll always be an engineering-led organization.” Marketing, finance, and product management can also feature in such statements. In fact, there are many versions of this claim by companies — and every one of them stinks. Here’s why; followed by a simple tool to help sidestep the alluring “we are led by X” pitfall.

In general, this whole way of thinking is wrong-headed for SaaS businesses, where organizational balance is key to sustainability. If one department or functional group within a company unilaterally leads, doesn’t that relegate all others to simply following the leader? Such an approach implies that those so-called secondary departments exist overwhelmingly in service to / support of that leading functional group. At best, this creates imbalance. Specifically, it sub-optimizes the potential of the whole organization, in favor of maximizing the output of one part of it. Worse, such thinking prioritizes pleasing internal “lead dogs” over the needs of important external stakeholders (e.g. customers, prospects, shareholders). This often results in unhealthy politics which eventually limit the growth and profit potential of the business. Regardless of which department we drop into this corporate Mad Lib, the outcome is consistently negative.

Beyond being a bad idea in general terms, “X-led” companies suffer unique downsides depending on which department occupies that leading role. Though the problems differ by department, they are highly consistent in how each appears from one company to the next:

Again, there are many variations of this same tune: Finance-led companies are fiscally responsible but can be brutally rigid workplaces. Even customer-led companies (as good as that sounds) often devolve into rampant incrementalism around customer feedback, risking eventual disruption by innovative market newcomers. Note: if forced to choose, I favor being a product-led company, as described by Marty Cagan in his excellent book, Inspired: How to Create Tech Products Customers Love. But even that can go wrong if implemented in a narrowly literal way (more on that in another post).

If any of these types sound familiar, you are not alone. To some degree this problem will always ebb and flow in organizations that are every bit like constantly evolving organisms. This makes it quite difficult to tackle this problem in its totality, without first mustering a ton of organizational will. Instead, one simple practice can improve life for all within any X-led company: rethink when each department engages with the others. Here’s how:

In an X-led organization, one department tends to act; and all other downstream departments are later forced to react. Of the many problems this creates, a big one relates to timing — when one department leads, all others are usually late to the game. For example, a company’s Client Success team will always struggle to delight the customer if they only learn after-the fact what commitments a salesperson has made in the sales cycle. Similarly, salespeople cannot credibly convey the company’s product vision to prospects, if they are only informed of the product roadmap as new features are being released. In both cases (and countless others in companies everywhere), the problem relates to WHEN one department is engaged by others. Two questions to ask in virtually every one of these situations are:

If this sounds simple, it is. But it is also effective. These seemingly simplistic questions never cease to foster a rich and wide-ranging discussion. They also inevitably reveal opportunities to move cross-department collaboration earlier in the value-chain, which yields demonstrable benefits. These include: informing more successful client implementations, surfacing development issues in a more timely / manageable manner, and driving more holistic support and activation of Marketing initiatives.

One last pro-tip for getting your money’s worth from such an exercise — invite every department to the party. Just as it is sub-optimal to have a company that is led by a single department, this exercise also suffers when it is undertaken by only one (or two) departments. Instead, it should be all-inclusive. When every department needs to answer these questions for each of its peers, it won’t be long before everyone leads…and everyone follows.

The number one reason startups die is that they run out of cash. This is well known; and plenty of resources currently offer excellent advice for surviving turbulent times. But this is scary stuff with existential consequences for small-scale businesses; and guidance around cash-preservation can be overwhelming for company leaders. Having experienced challenging environments in 2001 and (even more so) 2008, I remember making the mistake of being trapped for days in forecast models or repeatedly scouring a laundry-list of line-items to be considered for cost-cutting. I was mired in the tactical weeds and later came to appreciate that some broader perspective would have helped guide my approach. The purpose of this post is to share a few lessons learned on this front and to offer some high-level frameworks to inform the thought process behind cash-conservation efforts.

I. Secondary Goals / Sacred Cows: Leaders intuitively understand the goal of cash-retention initiatives — to survive. It’s quite simple; just don’t run out of cash. But it is never that simple; and that is why it’s helpful for leadership teams to clearly set secondary goals for any expense-management initiative. This approach answers the question, “what is the NEXT most important objective of this effort (beyond simply staying solvent)?” For some companies, that may be safeguarding the customer experience and brand loyalty. For others, it could be maintaining the engagement / continuity of the entire team or retaining top talent. For more mature businesses, it might mean ensuring the business is positioned optimally for whenever the economy eventually turns around. Another way to arrive at similar clarity is by identifying “sacred cows” — those parts of the business where compromises will never be made. Whichever route is taken, this exercise helps leaders keep one eye — even in a crisis moment — on what is important for the longer-term health of the business.

II. If / Then / Then-by-When: The purpose of this mnemonic is to help leaders rise above the detail of expense-management and think beyond the tyranny of spreadsheets. It forces execs to go through a three-step business planning process, as follows:

In sum, this framework forces structure in what can otherwise become an ad hoc reaction to environmental challenges. It demands that company leaders a) thoughtfully envision potential scenarios, b) identify the qualitative and quantitative impact of those environmental forces on their business, and c) codify the steps and related timelines needed to address the challenge faced.

III. Assumptions, Decisions, and Control: Re-forecasts are inherently unsettling; and it can be difficult to know where to begin. One way to get a foothold is to separate where to make “assumptions” and where to make “decisions.” A general rule of thumb is to make assumptions about the top-line (sales / bookings and corresponding revenue) and make decisions around expense management. Why?

The truth is that companies ultimately cannot control whether clients actually buy from them; so, they need to make educated assumptions about customers’ buying behavior. Further, we’ve found it helpful to first focus on (and make the most pessimistic assumptions about) the types of revenues that companies least control. This generally means new sales to new customers, since they are the most speculative and rely most on customers making a proactive and incremental outlay of cash. Then, we move methodically down the risk ladder. The next most at-risk revenue class tends to be expansion sales to existing customers. Then come usage-related revenues. Finally, existing client renewals tend to be the most secure (but still ultimately at-risk!). When companies have great data, they can even further refine their renewal assumptions based on cohorts (products used, type or size of customer, and date of initial purchase). Breaking revenue streams out in this way allows companies to thoughtfully and granularly quantify risk to the top-line.

When (and only when) a company updates its top-line expectations, they can then begin to make informed decisions about expense-management — because they ultimately control expenses and can manage them accordingly. It’s helpful to sequence expense related decision-making opposite to that on the revenue side. Start with the expenses over which the company has the MOST near-term control and work the other way. This is because controllable costs offer the best ability to quickly aid in cash conservation. Highly controllable costs are almost always discretionary / un-committed, non-personnel expenses (e.g. marketing campaigns). Month-by-month subscriptions tend to come next. Consultants and contractors are also somewhat manageable (albeit not nearly as easy to pare back). Drastic measures such as “reductions in force” are far trickier still; and long-term leases (e.g. rent and pre-paid annual contracts) are often most challenging to derive savings from in the short-term. The following graphic from an excellent recent study by A&M (Alvarez and Marsal) concisely captures these dynamics and expands well-beyond.

A note about the elephant in the room: By far the most excruciating expense-related decisions revolve around personnel costs of the core team. Unfortunately, this is also the richest vein to mine from an expense management standpoint, because the majority of expenses in SaaS businesses are people related (yet again proving the adage that nothing valuable is ever easy). Moreover, the dynamics of personnel decisions are deeply complex and interdependent both financially and culturally; and leaders need to make choices in this area with the utmost consideration and care. This topic certainly warrants a more complete discussion but is not the focus of this particular post.

Okay, so…with these frameworks in the toolbox…what comes next? As is often the case when it comes to operational execution, it starts with communication. A range of diverse stakeholders will be involved in, and impacted by, any of the activities described above; so clear, effective communication is key. Although these decisions are made based on data and reason, their communication demands empathy and compassion — none of us wants to be the leader who gets stuck in spreadsheets(!). In a world where working at a physical distance is not just a choice, but a necessary health condition, such compassionate communications are more important ever.

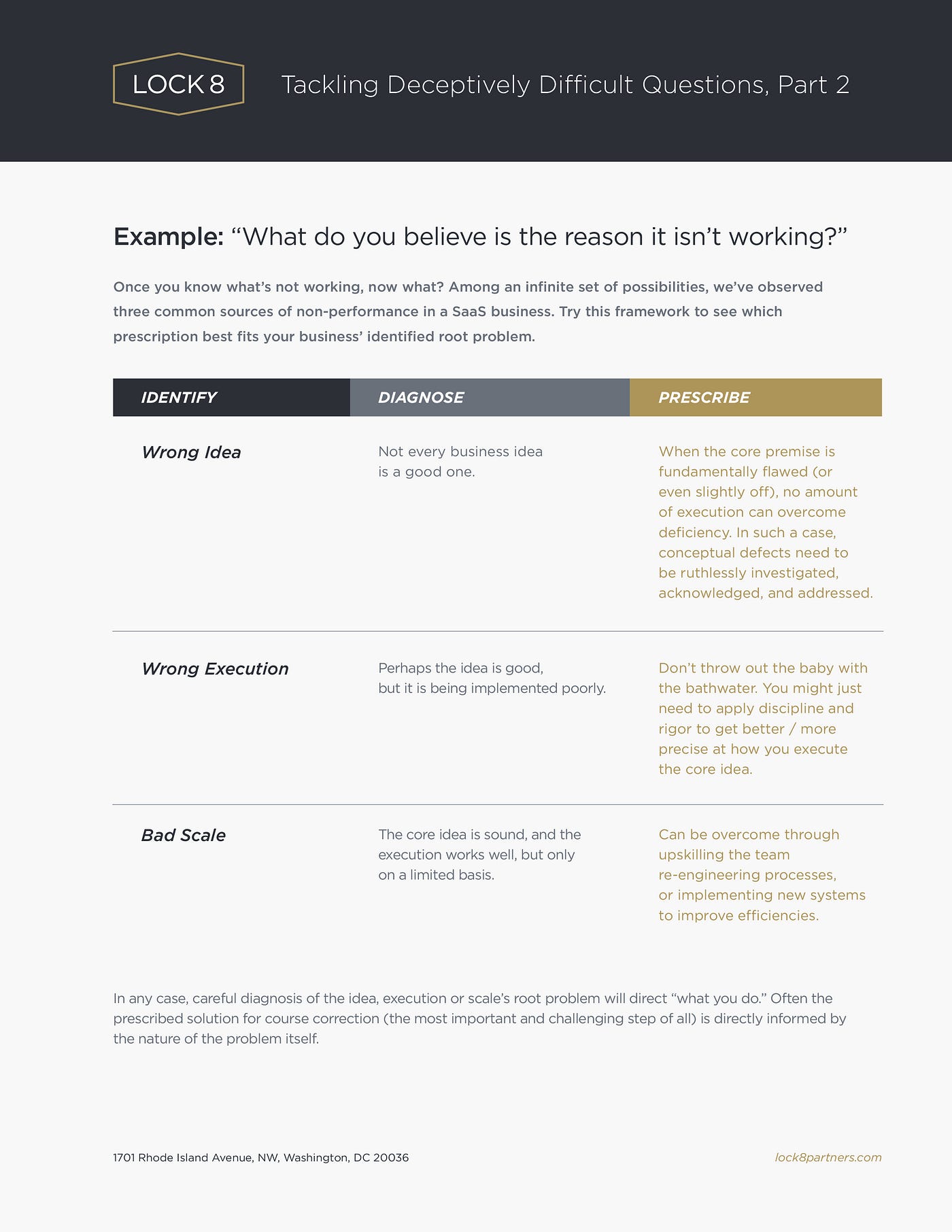

This blog recently featured a post that invoked the First Rule of Holes (“Stop Digging!”). That piece had been triggered by some business-planning discussions; and it advocated taking a structured approach when tackling deceptively difficult business questions. In that case, the seemingly innocuous question was “What do you do when it’s not working?” That post offered a framework to assist in the first step of problem-solving — actually identifying the existence of a problem in the first place.

This is part two of that post. It picks up where the last one left off: developing hypotheses to test why something isn’t working. Building on the initial framework, this piece endeavors to share a structure to use in the critical step of diagnosing the source of a business problem.

Strong communications skills are a must-have for any aspiring executive; and leaders in small-scale SaaS businesses need to be comfortable in a range of messaging situations. In these intimate, dynamic businesses, public speaking represents a major slice of a leader’s communications responsibilities. Executives’ speaking duties can take many forms, with a main one being at trade shows or conferences. At these events, the cardinal rule is knowing one’s audience, as discussed in detail here. But this same rule applies to all speaking situations and all audiences, of which leaders are faced with a broad span. Although this is a seemingly obvious point, it is frequently underestimated and poses a surprisingly tricky hurdle that blocks many leaders’ public speaking efforts. This post examines this issue and offers some simple ideas to help leaders navigate the complex and sometimes intimidating world of speaking to different groups.

To start, I want to refute the widely held notion that public speaking is an innate trait that some of us are born with (or, cursedly, without). While people undoubtedly start with a range of natural abilities, public speaking is an intricate skill that inevitably requires practice and discipline. The more practice, the better one becomes — obviously. But what is less obvious is that the environment in which one practices has a massive influence over how that competence evolves. To make this point, let’s take an example from the world of professional tennis:

Rafael Nadal is one of the world’s all-time great tennis players, having won 35 masters titles in his remarkable career. He has won the French Open a record twelve(!) times, including the recent 2019 crown. Conversely, he has won Wimbledon “only” twice, and not since doing so in 2010 at the age of 24. Why the discrepancy; after all, tennis is tennis, right? As it turns out, Nadal grew up practicing thousands of hours (literally) on the clay courts of his native Mallorca, Spain, which is the same surface on which the French Open is played. He is imminently comfortable on that playing surface, and far less so on the grass courts of Wimbledon’s All England Tennis Club.

Public speaking is very similar: we improve where and how we practice. I don’t mean the physical space (the playing surface is irrelevant here), but rather the types of situations we experience on a regular basis. In my experience, the most important factor in a presenter’s evolution is the kind of audience to which he / she becomes accustomed. This point was driven home recently by an executive with whom I was working. He has vast experience in sales leadership roles and is supremely competent and confident in front of prospects and customers. Having recently moved into more of a general management role, however, he suddenly has far more responsibility for presenting to internal audiences comprised of company-wide team members. He expressed that he finds the experience to be a new and different challenge, to which he is still becoming acclimated. He further shared that he currently requires far more presentation prep and notes in order to feel ready to present to this group. Given his background, this makes total sense; and it raised for me the following related observations.

A large part of leading SaaS businesses revolves around balancing the needs of different stakeholders, as referenced here and more briefly here. I often think in terms of a company’s four key sets of stakeholders: (1) its addressable market, (2) existing clients, (3) company team members, and (4) shareholders or owners. In the context of public speaking, it is helpful to think about these stakeholder groups and simply bear in mind the uniqueness of each as an audience. If nothing else, doing so can raise a presenter’s awareness around which audience represents a personal comfort versus one that may fall further outside his / her comfort zone. This alone can lead to more thoughtful and effective prep.

For some presenters, it can be helpful to overlay the concept of “altitude” on this stakeholder framework. Specifically, we often use the term “altitude” to describe the appropriate level of detail for a discussion or presentation. As a general guideline, each stakeholder group tends to have a different preferred altitude, or level of detail, at which they want to be engaged. This might look something like this:

Taking this concept further, presenters can further identify the general / typical information needs of each different stakeholder group. This might look roughly as follows:

Finally, it’s also worth noting that the each of these stakeholder groups is comprised of a rich and diverse set of sub-groups. For example, within a group of team members, the needs and perspectives of software developers will be different from those of salespeople or marketers. Likewise, in the shareholder category, existing owners who are current board members will have a very different viewpoint than prospective new investors. Further segmenting each stakeholder group can only help a public speaker to mindfully target content and delivery style to match the audience needs.

To finish at the beginning, public speaking is a critical tool in a business leaders’ toolbox. Knowing one’s audience is paramount across a wide spectrum of prospective speaking situations. And this framework can hopefully be helpful in making it easier for thoughtful leaders to prepare effectively and present expertly in any situation.

One of the benefits of the SaaS delivery model is that it enables an iterative approach to product development. Because of the relative ease with which software updates can be delivered, SaaS solutions evolve fluidly and organically, with small improvements, enhancements, and fixes introduced often in a seemingly steady stream. But this does not mean that major upgrades are a relic of the past or that big-ticket development initiatives are obsolete. Rather, even with the most thoughtful product planning, time has a way of cruelly revealing ill-advised feature choices, scale-limiting technology decisions, and ever-changing market needs. In this way, each incremental release of new code propels SaaS businesses along a predictable path toward a crucial and somewhat unavoidable question:

Whether to continue building onto an existing solution (with all its pros and cons), or to re-think the whole approach, with the benefit of invaluable knowledge learned over time?

Such initiatives come in many flavors and go by different names, such as: re-platform, major upgrade, re-write / re-build, next-generation development, future proofing, and addressing tech-debt, to name just a few. Nearly all successful software companies contemplate such an effort at some point in their life cycle; and it is a fraught decision with existential ramifications. While the benefits of these types of initiatives can be positively transformative, they also represent significant potential costs and risks (e.g. large investment of time and resources, opportunity costs for projects not pursued, freezing new client sales, brand-damaging disruption and alienation of existing clients, and loss of critically important subscription revenue). Having participated in a number of these major initiatives as an operator over the years, I’ve come to appreciate that these are extremely complex and there are no silver bullets. Likewise, every one of them is unique; and yet, these situations share numerous characteristics and dynamics, with applicable lessons to be learned from each. With that in mind, below are five quick observations and takeaways relating to this common, yet extremely high-stakes, situation.

Note: For simplicity’s sake, I’ve used the term SaaS throughout this article, although these principles apply to any number of modern software delivery models. This raises the important strategic decision of how to utilize cloud services while modernizing the architecture of a SaaS solution. I don’t intend to address that topic here, but will plan to tackle it in a future post.

While these concepts are applicable in many ways, they are just that — concepts. They need to be applied in pragmatic ways that make sense for each unique reality that SaaS businesses face. As stated above, there are no easy answers to solving to these supremely complex issues; but hopefully the tenets above will help folks navigate these major initiatives as they arise.

With those fateful words, the meeting ends on seemingly solid ground. Unfortunately, too often a team’s commitment begins to erode almost immediately after adjourning. In these scenarios, a corrosive force is hard at work, devastating teams and laying waste to even the most solid plans. It’s called re-trading, and it takes place when someone(s) revisits a settled decision with the intent to change plans after the fact. This post attempts to shine a light on the toxic team behavior and offer some thoughts for combating it. But first let’s take a step back and offer some context:

“Disagree and commit” is a management principle which states that individuals are allowed to disagree while a decision is being made, but that once a decision has been made, everybody must commit to it. According to Wikipedia, this principle has been attributed to such icons as Andy Grove, Scott McNealy, and Jeff Bezos. Whatever its true origin, it “pinpoints when it is useful to have conflict and disagreement (early states of decision-making, but not after the decision is made). It is also helpful in avoiding the consensus trap, in which a lack of consensus leads to inaction.” In general, this principle is useful in organizations that value different perspectives but have finite resources to pursue seemingly unlimited ideas (i.e. in most growing SaaS businesses). It works well, so long as people commit in good faith to a plan and then maintain that commitment even in the face of inevitable adversity. It fails miserably when people’s commitment wavers and they seek to revisit the original decision via a re-trade. The re-trade can present itself in any number of different forms, including:

Whatever the precise form, re-trading reflects an unhealthy team dynamic. Interestingly, re-trading rarely takes place within the context of an open setting (i.e. a leadership team meeting), but rather often in 1-on-1 conversations behind closed doors. This is a useless waste of time. It sows the seeds of mistrust (what are they whispering about in there?). It creates factions and unproductive conflict. Even worse, these discussions often spill over beyond the attendees of the original meeting. In this way, leadership team members can dangerously undermine their peers, which completely freaks out the broader team (no one’s happy when the “adults” bring “the kids” into their fight). Needless to say, if these whisper-campaigns gain traction, they can completely derail the original agreed-upon plans. Left unchecked, these side conversations can also have a debilitating long-term effect on future decisions. Specifically, if people believe that they can re-visit decisions after the fact without negative consequences, then they may be incented to simply lay-low during initial debates and surreptitiously seek to get their way later-on. In short, once re-trading becomes normalized, no future decision will ever be safe from the threat of a re-trade.

On the contrary, in his classic book “The Five Dysfunctions of a Team,” Patrick Lencioni offers a succinct description of how truly cohesive teams behave:

Lencioni’s model also offers insights regarding ways to combat the re-trade. As I often say, there is no cure-all for human behavior. But if re-trading blooms in darkness, then sunshine is the best disinfectant. Specifically, pre-emptively calling out the dangers of re-trading goes a long way toward helping teams arm themselves against it. Unlike Voldemort in the Harry Potter series (“He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named”), openly acknowledging the potential for re-trading raises people’s awareness of and vigilance against it. Naming and shaming this behavior can give team members language to identify and resist peers’ efforts to engage in after-action 1-on-1 gripe sessions (a central means to waging a re-trading initiative). It also allows leaders to establish criteria for when it is appropriate to re-open past decisions. Specifically, facts and circumstances do change over time. And, if the realities on the ground justify it, then decisions absolutely should be reconsidered by the team. By establishing this as the one reason to re-open prior decisions, leaders can set a high bar for when / how / why plans can openly be re-litigated. Finally, because an ounce of prevention truly is worth a pound of cure, Lencioni’s model offers good guidance on how to address the root cause of re-trading. Maniacal focus on building trust and embracing unfiltered conflict early-on in decision-making processes will always be the best way to avoid downstream re-trading and all its devastating effects.

“So, we’re all in agreement, right? Great, let’s do it.”

In 2014 I found myself leading a SaaS business with a problem: how to hire executives to manage our company’s significant growth. It was a good problem to have, for sure; but it was still a problem. So, we scoped roles, identified job qualifications, established interview processes, activated our networks, and engaged recruiters. But mostly, we hoped. We hoped like crazy to avoid making a bad exec hire, which we knew would leave a trail of pain for months to come.

I was reminded of this personal experience last week while discussing the topic of exec hiring among a small group of entrepreneurs/operators. People consistently shared experiences of having anxiously faced, often unsuccessfully, this quite common business challenge. One entrepreneur helpfully shared the “GWC” framework that he had discovered while implementing the EOS Model outlined in the book Traction. The GWC framework is explained here, but the gist is that you should only hire people who:

In considering this framework, I realized that many businesses tend to over-index on the C (Capacity) in the hiring process. No surprise there; it’s understandable for us to optimize around finding someone who has the skills, experience and capabilities to get the job done. In fairness, many organizations fully appreciate the importance of culture and fit; so, the G (Get it) also gets strong consideration. But the W (Want it) often gets lost in the shuffle. Perhaps we are prone to assume or overestimate the degree to which someone wants to work at our companies. For whatever reason, the W receives less thoughtful examination compared to diligence around the G and the C. Reflecting on dozens (hundreds?) of hires over the last 20 years, I’m struck by how backward this is.

When I think about the truly great hires we’ve made, virtually every one of them had a very high W-factor. These are the folks who would run through walls, and whose desire was infectious. Conversely, I suspect that we can all recount failed hires where the C (and even the G) were very persuasive…but the W just wasn’t quite there. I’ll go one step further and say that a hire with a strong W can bridge gaps in their C and G (“where there is a will, there is a way”); but the converse simply isn’t true. Precisely why someone “wants it” is irrelevant, and the W can come from a wide range of circumstances; but it absolutely needs to exist.

To paraphrase the Rolling Stones: You can’t always get what you want; but hiring “want it” will definitely help get what you need.

I have admired the work of Walker White for years and have valued the opportunity to compare notes and share lessons-learned with him during that time. At this point, I am excited to explore ways to expand and deepen that collaboration. With his recent transition following a long and successful run at BDNA and its acquirer Flexera, Walker will play a more active advisory role to Lock 8 Partners. This week Walker shared on LinkedIn some of his thoughts and observations from 25 years in leadership roles in the tech space. His post really resonated with me, and I wanted to share it here on the Made Not Found blog.

After 25+ years, it is time for me to shake it up and pursue career 2.0. I’ve been fortunate to be entrusted with leadership roles over that time, and in an effort to continue learning, I kept a running list of quotes and anecdotes that struck me. As it is good to pause and reflect during any transition, I recently found myself reviewing that list. Sometimes with a chuckle and other times with a sigh, I was reminded of when I heard them, what they meant to me, and how I put it into action (or didn’t, hence the sighs). I thought I would share four of my favorites:

When you hear a quote or anecdote that resonates with you, take the time to jot it down. In my experience, so much of leadership is common sense, but the pace of the day-to-day often caused me to over think the best solution. Simple quotes — like those above — always served to ground me back to what really mattered and more often than not illuminated that which I had overlooked.

Still learning and laughing,

Walker White

Walker White recently left his role as Senior Vice President of Products at Flexera to pursue Career 2.0. Prior to acquisition by Flexera, Walker White was the president of BDNA Corporation. He is passionate about helping organizations excel by building the right team and culture, setting and communicating a compelling vision, and driving momentum through courageous decisions.