A previous post on this blog outlined the struggle that many SaaS businesses face in driving a company’s product vision, strategy, design, and execution. That prior post offered some general concepts and terms aimed at demystifying this weighty responsibility, which includes codifying a well-informed product idea into a clear and compelling vision, and then translating that vision into a manageable action plan for a team. For the sake of brevity here, we’ll call those collective efforts “product management.” This post tackles the same topic, but instead examines how organizations evolve and mature in terms of developing product management capabilities as a core SaaS discipline.

Why focus on this topic? First, because product management is really hard; and many companies struggle with it. Second, because virtually every product management organization is trying to improve. And third, because we as humans inevitably want to run before we can walk. Similarly, many organizations naively desire to jump directly from their current-state (whatever that may be) into being a sophisticated, best-in-class product management machine. But it doesn’t work that way; there are no shortcuts. Rather, to be able to run a marathon, we need to commit to lacing up our metaphorical jogging shoes and following an increasingly rigorous training plan, in order to properly prep for race-day.

To be clear, this post does not pretend to be a step-by-step product management training plan. Rather, it intends simply to offer a competency model that captures what we’ve observed across many years and multiple SaaS businesses. Specifically, it lays out a competency framework for thinking about key milestones along an organization’s evolutionary journey in product management. Again, why? Because, although it is helpful to know what “great” looks like, it is also valuable to have a clear vision for what is one step beyond today’s current state. And, because every great journey starts with a single step, let’s get going.

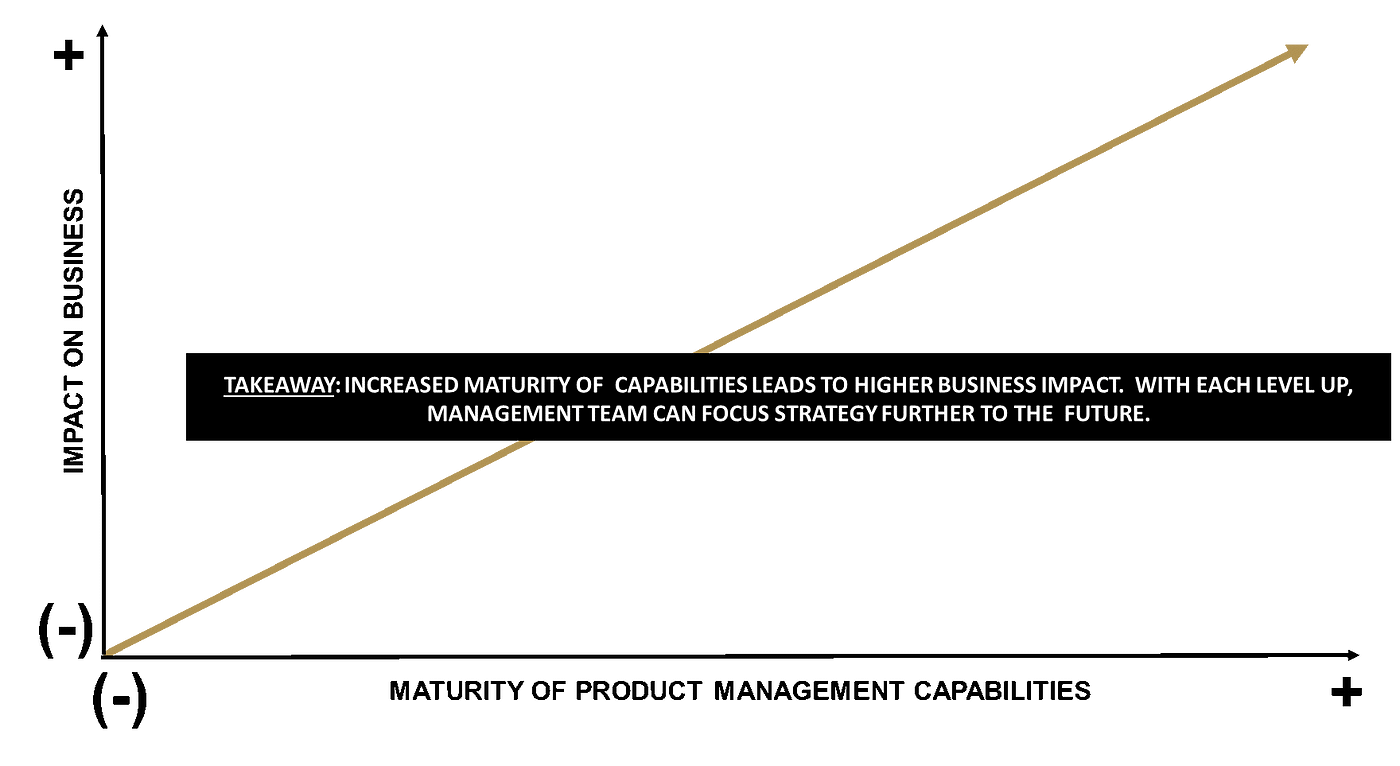

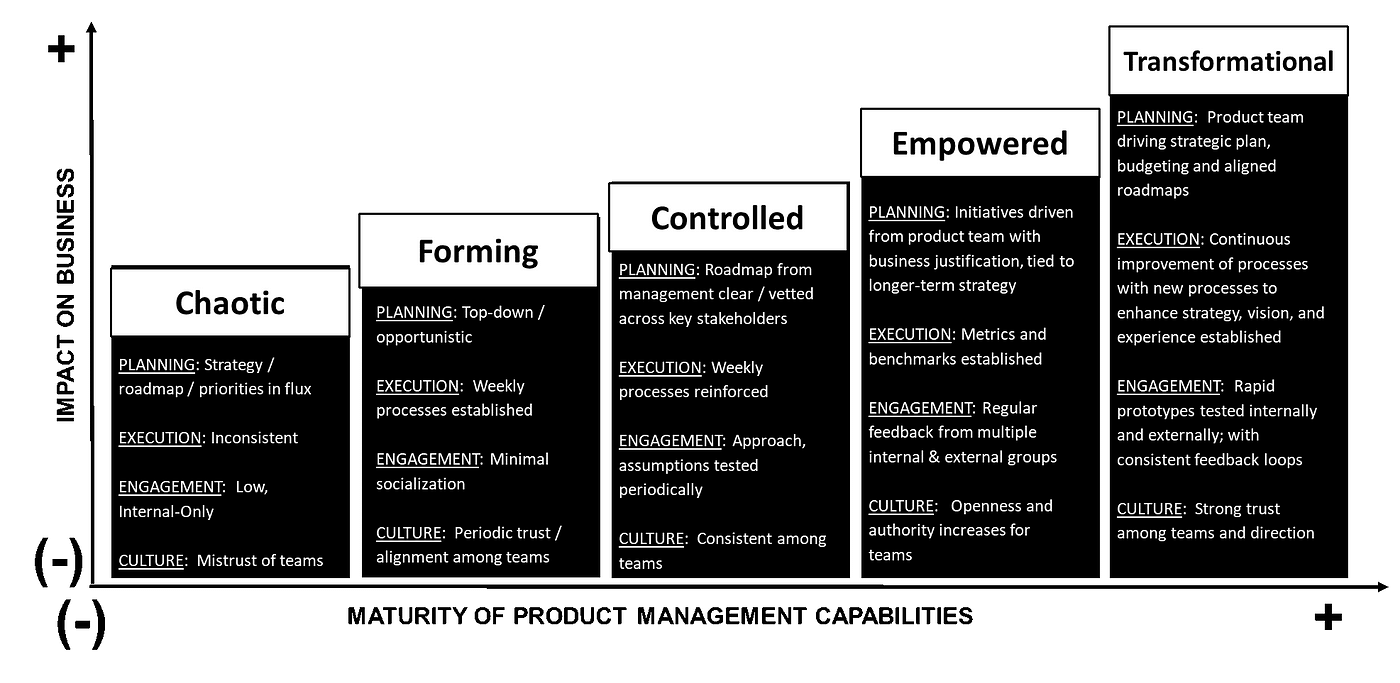

First, we’ll need to agree on a simple premise: the better an organization is at product management, the greater and more positive that function’s impact is on the current and future performance and outcomes of a business. Now, if we were to plot that concept on X and Y axes, it might look something like this:

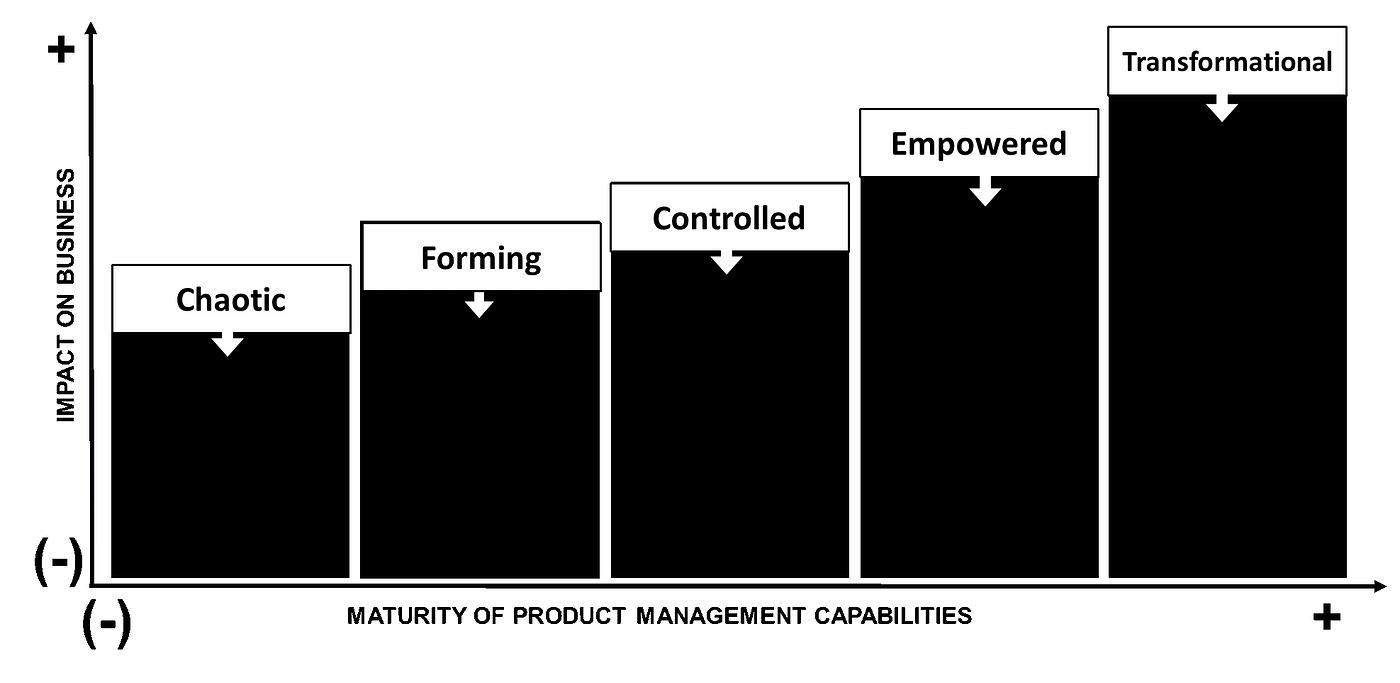

Setting aside for one moment the wide-ranging skills and capabilities that fall within the general heading of product management, let’s also agree that product management competency can range from very low (poor) to very high (expert), offering two ends of a spectrum. Using the “Maturity / Impact” construct above, it’s fair to state that the very lowest performing product management function has a correspondingly low (or even negative) impact on the related business. One might even say that the impact on the business is one of creating “chaos” (or at least failing to avoid it). Conversely, the most highly evolved product management organizations have a massively positive effect on their companies / products / customers. We’ve observed this to have a “transformational” impact on those same sets of stakeholders. In between these two poles, there are increasingly impactful gradations. We tend to think about it in the following five phases of maturity / evolution, as follows:

Please note: the above is NOT scientific or drawn to any scale. If it were to be drawn to scale, however, I believe the positive impact of Transformational product management capabilities (the last bar of the graph) would be orders of magnitude higher than the Chaotic or even Forming PM capabilities bars. They are simply incomparable in value.

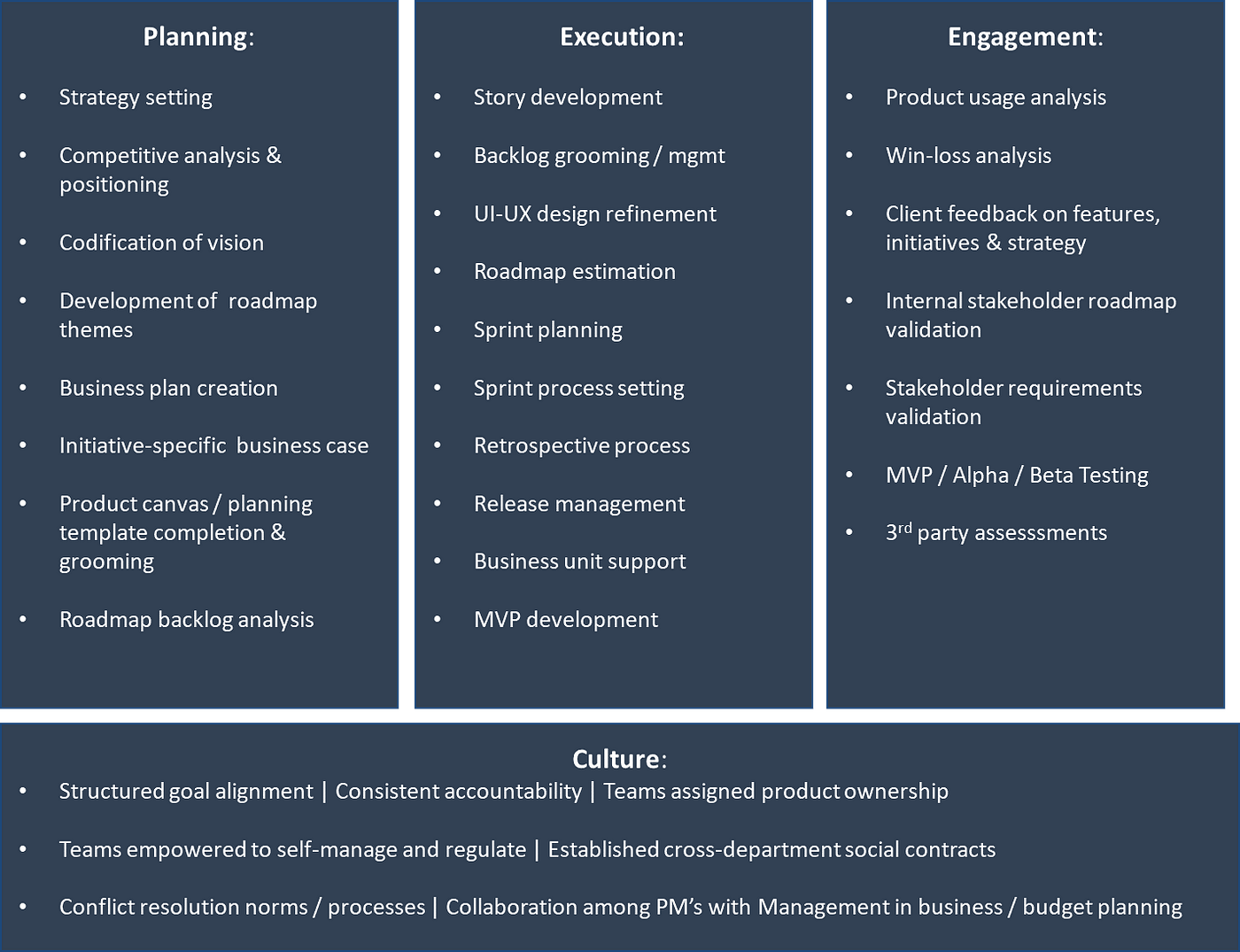

Separately, there is another dimension to all of this; let’s turn our attention to the buckets of activities that comprise the product management function. Although there are countless ways to think about these responsibilities, we like to think about them in four general categories, as follows:

Within and across these four categories, there are a virtually limitless set of activities or tasks for which product management is responsible. The graphic below lays out a representative set of activities; and we think these are some of the more important ones. Because Culture supports and enables the other three categories, we draw it as follows:

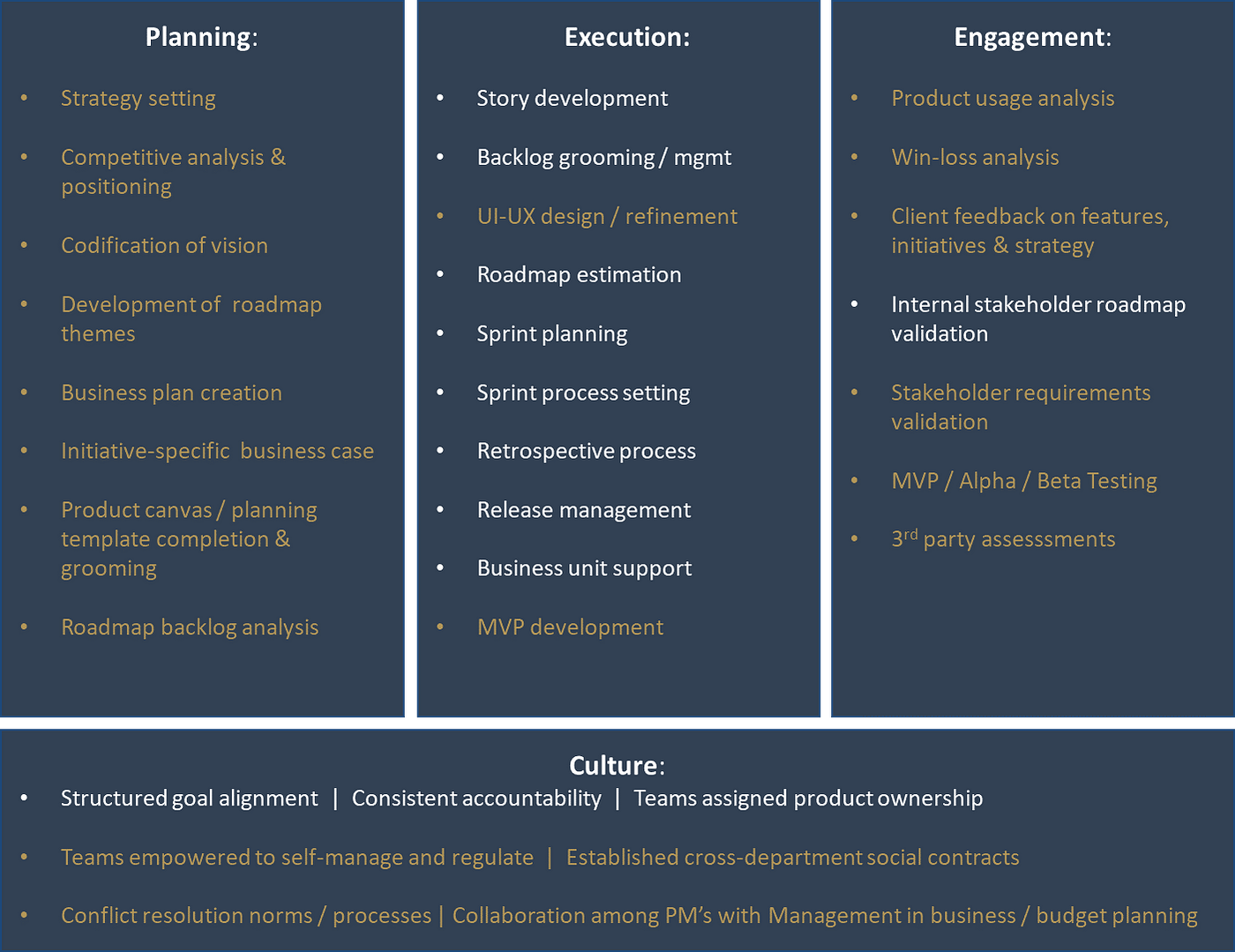

Hopefully none of these bulleted items are terribly surprising to anyone who has spent time in a SaaS business. Unfortunately, there is a gap between knowing and doing, so a number of these items are frequently neglected or only nominally completed. In fact, when color-coded for what is comprehensively addressed (WHITE) versus NOT well-covered (GOLD) in a typical small-scale company, the list might look more like this:

Said another way, small-scale SaaS companies’ product management competency can be quite high in some areas, but quite low in others. And while this is arguably interesting in its own right, these activities become much more useful when overlaid with the phases of maturity outlined above. Specifically, performance levels across these categories dictate where an organization falls on the Maturity / Impact graph introduced at the outset. The graphic below identifies how Planning, Execution, Engagement, and Culture look at various phases of Maturity / Impact. This graphic brings it together, as follows:

Hopefully this model is helpful in its own right. But what we have found most valuable are the insights it has helped catalyze within SaaS businesses. I’ll share one of ours here:

Sample Learning: The framework allows managers to more easily and granularly understand how their teams are spending their time. Specifically, it was only when we bucketed activities, surveyed teams, and color-coded activities that we began to pinpoint unhealthy imbalances in allocation of time and resources. What we learned was that growing SaaS businesses we work in tend to be very focused on (and good at) cranking out the most pressing work (Execution). In fact, we’ve seen teams that focus 90% of their time on delivery of the current roadmap. Conversely, these companies tend to vastly under-invest in thoughtful, rigorous Planning, which can account for less than 10% of a product team’s time. Likewise, few resources tend to be directed toward getting consistent, multi-sourced feedback about that work (Engagement). If time and talent are a company’s most valuable resources, we should undoubtedly make sure that we’re using them wisely, through better Planning and Engagement. What this framework also taught us, unfortunately, is that you are only as good as your worst weakness. In other words, even if you are highly evolved in Execution or even Culture, you simply can’t make major strides forward on the Maturity / Impact framework if your Planning and Engagement are holding you back or dragging you down.

Having said all of the above, the looming question remains — what can product management organizations do to improve? In other words, how can we jump to the right on this Maturity / Impact graph? And, more tangibly, what tools or exercises can we implement to help get us there? Having now introduced this framework, it’s my plan to go into some of these tactics and tools in future post here on Made Not Found.

Thank you: I’d like to acknowledge and thank my good friend and former colleague Paul Miller for his contributions to this post. Paul has a clear, disciplined, creative product mind; and his thoughts shaped much of the above. It’s been fun noodling these ideas over the years with Paul; and he has been an invaluable collaborator in our shared and never-ending effort to get better at product management.

A core marketing objective for many B-2-B SaaS companies is to raise their profile by presenting at industry conferences. In theory, it seems like a surefire way to get your message to the right sets of ears. What could be better than presenting a session to a room full of prospective customers on a topic that is in your wheelhouse and gives you a chance to shine a light on your company’s value proposition? Unless…

The truth is that this can go wrong in so many ways. In fact, we’ve all probably been on the receiving end of some brutal presentations. But why the disconnect? What is it about industry conference “vendor” presentations that makes so many of them boring, ineffective, uninspired, or the perfect opportunity for attendees to check email? Having been to a lot of conferences over the past two decades, I’ve concluded that there are countless ways to mess this up…but that mistakes tend to fall into only a small handful of buckets. The following post lays out (in no particular order) seven “deadly sins” committed by us presenters — and how to avoid falling prey to their temptation!

1. Not Knowing (or Caring) Enough About the Audience

Anyone who’s ever received any training in presentation skills has probably heard this advice — know your audience. Although we all nod our heads in agreement, we generally don’t follow this wise guidance. Rather, presenters often proceed with materials largely unchanged from prior talks, other than maybe a few altered jokes. In a busy world filled with competing priorities, that’s the easiest approach…and it usually bombs. Here’s why:

Knowing your audience means caring enough to learn what they want from you.

This requires taking the time to step inside the shoes of audience members, NO MATTER THE TOPIC. For example, let’s say your topic is [X], and you want to emphasize the importance of [X] as a strategy to boost company performance. Now, imagine how a talk on this subject would be perceived differently if you are speaking to a room full of system administrators versus a room full of CEOs (or developers or marketers). Each is totally different. While CEO’s (hopefully) will appreciate what you have to say about [X] and performance, the audience of system administrators will likely have a very different experience. If you don’t thoughtfully alter your approach, at least one of those two audiences will likely have a sub-optimal reaction. They won’t find your clever jokes about [X] to be all that funny; and they might spend the session thinking about the many ways they understand or view [X] differently than how you describe. They may politely pay attention for most of your talk; but they are equally likely to leave scathing reviews on the speaker evaluation forms for the session.

You could have the audience members sitting on the edge of their seats — if you understand why they are sitting there in the first place.

Now imagine that rather than just repackaging the same tired routine, you stopped to think how you might approach the same topic differently from the perspective of the audience. You might have created a presentation on “how to be an effective executive leader in connection to [X],” or rather a session on “how to encourage effective use of [X] from those who may not even yet have heard of [X].” You could have provided a brilliant step-by-step guide for a target audience on how to use [X] to advance your career and build your network. You could have had them sitting on the edge of their seats.

As an example, there was an amazing Evangelist at one of my previous companies who would take the same general topic and completely transform the thrust of her presentations for senior executives (outcomes and impact), executive administrators (process improvements / time savings / efficiency gains), technologists (innovation and macro-trends), and CFO’s (risk, compliance, security).

Understanding your audience means you’ve made the effort to really understand what motivated that particular group of people to come to that session. That effort enables you to predict what will make the session as valuable as possible for that group, on that day, in that venue — and to adapt your presentation and your speaking style to deliver it to them.

2. Trying to disguise a blatant sales pitch with a clever title

First, I totally get it: public speaking at conferences can be expensive, time-consuming, and uncomfortable (public speaking is scarier than death to many); so you want to get something out of it. At some level, it is a means to an end — selling your SaaS product to the audience. And you may even believe so strongly in your solution, that the audience — once they learn about how awesome your product is — will forgive a few minor commercial plugs within what was supposed to be an educational speech. And because it’s just so good, you find yourself giving a quick sales pitch, product demo, or feature-focused walk-through of what your company offers. Sadly, believing something doesn’t make it so. Rather, nobody — zero people — will have more respect for your presentation, your company or your products if you do the old “bait and switch” routine.

If the title of your presentation promises a learning opportunity — then teach to the subject matter. If you’re truly knowledgeable in a specific area, and your presentation provides compelling evidence that would lead any sane person to the obvious conclusion that a productized version of your knowledge may be the solution to their problems, then you’ve done a great job. If, however, you feel compelled to blatantly tell the audience all about your solution, while the title of your session promises something different, you will have lost them in the first 30 seconds of speaking.

3. Creating a Slide Deck That’s Better Read than Said

We have all sat through presentations where the speaker simply read aloud what was already plainly written on the accompanying slide deck. And we’ve all had the same thought — “this is a complete waste of my time.” But there is a more insidious version of the deadly sin of reading your slides aloud — presenting an exhaustive, text-laden slide deck. While I readily acknowledge that there are places in the world for dense “briefing decks,” industry conferences are NOT among them. Rather, entrepreneurs / operators requested to present at industry conferences have a forum to educate, entertain, and engage the audience. The presenter’s goal should NOT be to present everything he/she knows about a particular topic, but rather to leave them wanting more.

To that end, your slide deck should seek to provide quick, impactful visual cues that give you a chance to tell an interesting story. If you’re like me and you tend to forget specific data points at times, it’s completely acceptable to write these data points in the presenter’s notes section. But the slide that the audience sees should only provide enough information to engage the audience. The best presentations I’ve ever attended actually had shockingly few words on slides. Rather, they were filled with provocative images that cued the presenter to tell an interesting story. Some really talented presenters (like Simon Sinek) rarely uses slides at all, opting instead to use a blank piece of paper and a marker to draw a concept real-time. Such presentations are memorable, easily repeatable, and compelling — precisely because they don’t use text-laden slides as crutches to do presenters’ work for them. Tip: many presenters spend 90% of their prep time creating slides, and 10% practicing what they’ll say. Flip those ratios; and see how it goes.

4. Attempting to Tell the Audience Everything You Know about a Subject

I’m clearly not the first to suggest that presenting fewer pieces of information through a handful of compelling stories is a successful presentation strategy, but it bears repeating. We humans are terrible at memorizing multiple complex ideas in a single sitting. We are far more likely to remember how the speaker sounded and looked than recalling a laundry list of important points.

Knowing this reality, do yourself a favor and present less stuff. Pick the 1–3 salient points that you know will be a home run with your specific audience, and then come up with interesting stories you can tell that make your case for you. Then create a slide deck with images that prompt you to tell your stories. I’d argue the greatest feedback any presenter can receive from a session is something along the lines of, “This session was really good, I just wish it had been a little longer.” Tip: Beyond limiting the number of points you make, no one will EVER be unhappy if you finish your session a little early; so keep it light.

5. Filling Your Entire Speaking Session with YOU

When entrepreneurs / operators are given a speaking slot at industry conferences, invariably the audience is wary. Generally, they want to avoid being “sold to” or “boasted at.” Meanwhile, the presenter is also wary — they want to be perceived as knowledgeable and authoritative (none of us wants to look silly or stupid). So, presenters often attempt to establish their credibility by sharing their qualifications…and commit the deadly sin of making the presentation all about them. This inevitably backfires with the audience. The moment a presenter fills too much time with the many ways he / she is personally and professionally wonderful, you can almost hear a “whoosh” as audience members picks up phones to check Slack or Twitter.

Your job as a presenter is to give the audience the information they want (see point 1). So, don’t be tempted into thinking that the best way to win over the audience is to prove how smart, capable and successful you are. Having witnessed this approach many times, this rarely works. Rather, the presentations that receive the greatest buzz are those where the audience is engaged — where the presenter goes out of her / his way to make as much of the material about THEM as possible and only about her / himself when providing a more personal anecdote would illustrate a point in a humble, unassuming but totally identifiable way. For example, I’ve learned that poking fun of my own baldness offers a way to quickly inject some relevant personal experiences, while still keeping the tone appropriately self-effacing (warning: only try this if you are, indeed, bald).

Another strategy that can be successful — when done right — is to share the limelight by creating a panel of people who will discuss a topic. But beware — when done wrong, panel sessions can become the deadliest of sins (see below).

6. Facilitating a poorly planned, really dreadful panel discussion

It seems like such a foolproof way to win over your audience: simply pick a compelling topic, create a panel of 2–3 smart people (potentially customers and fans of your company), and then just ask them a series of questions. Right? Well…maybe. The panel CAN be a successful way to accomplish a few objectives easily:

But this approach can utterly fail if you as the moderator don’t bother to understand the nuances of how each panelist differs, what unique information or strengths each panelist brings to the discussion, and the best way to cue each panelist to deliver the most salient information. We’ve all seen panel sessions that were moderated poorly — where the moderator lazily asks every panelist the exact same questions, and each panelist (to avoid seeming either unprepared or impolite) just agrees with everyone else on the panel, and then tries to add a unique spin that really is just a paraphrase of what has already been said. Other panel moderators seem to think that having a panel absolves them of any prep work — like they can just show up and start asking random questions to a group of strangers and magic will somehow “happen.” Not so. Rather, the moderator has one very important responsibility:

The panel moderator’s job is to help panelists tell compelling stories that make the panelists look their best.

If you do this right, the panel discussion can shine a bright and favorable light on you and your company — because you are obviously the kind of SaaS leader who actually cares to get to know people. You care so much, you understood that the CEO from the hospital who was on your panel had very different challenges than the General Counsel of the family-owned company — and you skillfully selected (with ample pre-session prep calls with the panel) just the right questions to pose that allowed each panelist to shine as they told a really interesting story. You made it look like the group was up on the stage enjoying a riveting conversation — one that the audience just happened upon and is now sitting on the edge of their seats dying to know what’s going to happen next.

Which brings us to the final deadly industry conference presentation sin.

7. Calling yourself a panel moderator, and then behaving more like a “puppet-master.”

As described above, a good panel discussion requires a moderator who understands each panelist’s context, way of thinking, and knack for speaking — and who has carefully curated a set of questions designed to help each panelist showcase their best selves. Woe to the moderator who falsely believes that what the audience really wants is to hear her/him answer every question alongside (or instead of) the panelists. A cousin-sin to this is when the moderator feels he / she needs to synthesize and summarize all of panelists responses. There are many versions of this, and they all can appear scripted, unauthentic, and self-serving.

In short, if you’re going to invite panelists to join you on stage, recognize that they have an opportunity to help your message shine — but only by being their authentic selves. It’s completely acceptable for you to cultivate a discussion on-stage — even a contentious one — as long as it’s all done in a respectful way, where each person has the opportunity to share diverging viewpoints without attacking each other (attack the ideas, not the people).

The truth is that these sins are easy to spot, and very hard to avoid committing ourselves. I hope this post is helpful in avoiding them in any future presentations.

I have admired the work of Walker White for years and have valued the opportunity to compare notes and share lessons-learned with him during that time. At this point, I am excited to explore ways to expand and deepen that collaboration. With his recent transition following a long and successful run at BDNA and its acquirer Flexera, Walker will play a more active advisory role to Lock 8 Partners. This week Walker shared on LinkedIn some of his thoughts and observations from 25 years in leadership roles in the tech space. His post really resonated with me, and I wanted to share it here on the Made Not Found blog.

After 25+ years, it is time for me to shake it up and pursue career 2.0. I’ve been fortunate to be entrusted with leadership roles over that time, and in an effort to continue learning, I kept a running list of quotes and anecdotes that struck me. As it is good to pause and reflect during any transition, I recently found myself reviewing that list. Sometimes with a chuckle and other times with a sigh, I was reminded of when I heard them, what they meant to me, and how I put it into action (or didn’t, hence the sighs). I thought I would share four of my favorites:

When you hear a quote or anecdote that resonates with you, take the time to jot it down. In my experience, so much of leadership is common sense, but the pace of the day-to-day often caused me to over think the best solution. Simple quotes — like those above — always served to ground me back to what really mattered and more often than not illuminated that which I had overlooked.

Still learning and laughing,

Walker White

Walker White recently left his role as Senior Vice President of Products at Flexera to pursue Career 2.0. Prior to acquisition by Flexera, Walker White was the president of BDNA Corporation. He is passionate about helping organizations excel by building the right team and culture, setting and communicating a compelling vision, and driving momentum through courageous decisions.

“We all want strong culture in our organizations, communities, and families. We all know that it works. We just don’t know how it works.”

This short video takes a quick look at this great book and adds a few thoughts for those looking to put some of its ideas into action.

Hopefully, this added perspective will make an already awesome book that much more actionable and valuable to leaders of growing organizations.

Cats and dogs. Oil and water. Hatfields and McCoys. Some things just don’t play well together. In fact, they seem almost purpose-built for conflict. I was reminded (again) this past week that the SaaS version of such predictable tension is the running feud between Sales and Client Success departments. There is undeniable and inherent tension between the two groups, and it’s easy to see why: the remit of Sales is to maximize bookings / hit targets in the immediate-term, whereas Client Success is responsible for turning every customer into raving fans long into the future. But this doesn’t need to lead to incessant battling. In fact, I’ve found that a few simple exercises can go a long way toward disarming the inter-departmental combat.

1. People Are People

I’ve observed that a fair bit of this conflict stems from a simple value-perception problem. Specifically, bookings are valued very highly in young SaaS businesses, with new sales (and often Sales people) celebrated as a life-line during a company’s fragile, early days (I wrote a bit about this here). Somewhat irrationally, those same organizations tend to be less overt and unrestrained in celebrating renewals, which lead to multiple years of recurring revenue. The predictable result is inequity in terms of how team members in Sales and Client Success perceive they are valued in the business. This, in turn, can breed resentment and conflict. A simple solution to this pervasive problem? Have the groups talk about it. But, to avoid reverting into counter-productive naming and shaming, be sure to do it in a thoughtful and structured way. I particularly like the following simple exercise:

With each person using a sheet of paper, ask people from Sales and CS, respectively, to privately rate and record on a scale of 1–5 their responses to the following two questions:

Then have them exchange papers and discuss. No matter the written responses, substantive and productive discussions generally ensue. Why?

2. We Mock What We Don’t Understand

Let me say that I just don’t buy the argument that Sales and CS people are just intrinsically different and incompatible. Rather, my experience is that they both want the same things — to win in the market, for their customers to be successful, and to thrive as a company and as individual professionals. The two groups just define and prioritize those objectives differently, (which is hardly surprising, given their respective areas of responsibility).

Beyond that though, the groups generally just don’t understand each other well. Again, this is unsurprising: SaaS businesses are fast-paced, resource-constrained environments. So, it’s far too rare that people receive adequate training on their own job function, let alone on the responsibilities of others. As a result, people have only a vague understanding of others’ work and almost no appreciation for the things that can make that work difficult or frustrating. And while people are hyper-aware of what they themselves produce, they are far less cognizant of their cross-department colleagues’ work product. The exception to this, of course, is when their peers’ actions make their own job more challenging…in which case the cross-department ceasefire is cancelled and hostilities resume. The painfully obvious (but difficult to execute) solution: educating people about the inter-dependent nature of their departments. For this, I like an exercise that centers around what each job function (a) produces and (b) consumes from the other.

Instructions: Ask members of Sales and Client Success to work together to identify 3–5 things for each of two categories:

I specifically like to create a grid where groups can brainstorm in isolation about what one department produces for the other. And then you do the same thing for what that department consumes from the other. Then switch departments. Because people from different departments are working as one group in this exercise, it tends to highlight just how different their perceptions / responses / pain points are at the outset…and how much and how quickly they learn to bridge the gap. I’ve focused this on Sales and CS here, but I like to do this one across all departments. The end result of this is a Give-Get Grid, which I wrote a bit about here, and which I’ll go into in more depth in a future post.

3. Our Strengths are Our Weaknesses

I’m a fan of the Gallup StrengthsFinder assessment for many reasons. Among them is the fact that it gives us language to call someone out for counter-productive behavior, but to do it in an inoffensive way. Specifically, StrengthsFinder is a diagnostic that allows people to identify what their core strengths are in terms of how they think, work, and view the world. Like many diagnostics, the explanatory write-ups for each of the framework’s 34 Strengths tend to resonate clearly with people when they receive their personal test results. And one of the most valuable parts of the assessment, for our purposes here, is how it convincingly and pragmatically points out this truism: our greatest strengths — left unchecked — frequently also present themselves as our great weaknesses. For example, “people exceptionally talented in the Activator theme can make things happen by turning thoughts into action. They want to do things now, rather than simply talk about them.” This is awesomely valuable when the situation demands speed. But this inclination can be counter-productive in situations that require great care, planning, or coordination. Likewise, Activators can be incredibly aggravating to those for whom Focus — “following through and making the corrections necessary to stay on track by prioritizing, then acting” — is their top strength. In such a case, it is undeniably better for the Focus person to politely / humorously ask the colleague to “tamp down their Activator tendency” than it is to tell them that the whole team wants to strangle their impetuous, hyper-active, cowboy throat. You know how these conversations can go…

Give People a Pass:

In closing, I want to broaden the scope beyond Sales and CS to cover all departments; there is a degree of tension among all of them, and they can all stand to examine how they intersect. I also want to acknowledge that these minor tactics / frameworks may be powerless in the face of true interdepartmental dysfunction or deep personal animosity among team members(!). But if that is the case, then more serious measures are likely needed to change the team…or change the team. That said, I’ve observed that most issues arise in an environment where different departments truly do share goals and respect for one another — they just need help getting aligned.

In such cases, we all need to step back and just give people a break. That’s right, give them a pass, and lay down your inter-departmental arms. Recognize colleagues’ perspective and take the high road, already! The Hatfield-McCoy thing does no one any good, and more importantly, isn’t worth the distraction from the ever-pressing needs of clients and the business at large. Frankly, it’s a pure waste to dwell or be mired in it. Use it; work it to affect mutual advantage and company success. There is usually a way. Find the leverage. It’s there to be found.

The other day, I re-discovered this great post by Theo Priestley of Forbes explaining why “Every Tech Company Needs a Chief Evangelist.” Re-reading this after a few years brought up positive thoughts about this role and fond memories of having encouraged a particular team member to consider becoming a technology evangelist back in the day.

Some backstory: at the time, the person in question was in the wrong role — one that was important to the company, but which did not play to her strengths. At the same time, our small-scale company and product category needed a strong spokesperson — someone who not only believed in our company’s mission and solution, but who could expertly recruit others to share in our enthusiasm. We were fortunate that this hiding-in-plain-sight “evangelist” had been with the company from its earliest days, and had all along been winning followers to our cause — far in advance of officially assuming the title “evangelist.” What follows is a compilation of questions and observations about that experience and more generally about the evangelist role in SaaS businesses.

So…what exactly is a technology evangelist?

Truly effective evangelists play a special role in the growth of SaaS companies. Whether or not they bear that specific title, you probably have encountered these people along the way. You know these folks when you meet them by the excitement they feel to tell you about what their company brings to the world. As they speak, you find yourself getting swept up in their enthusiasm. They are completely genuine in their belief that the work of their companies will change the world. They can articulate clearly and authentically how the world will be different once their companies have reached critical mass in the marketplace. They are intimately familiar with the technology behind your company’s products, but where they truly get their energy is in discussing the problems those products solve for people. This, more so than any technical knowledge, is what speaks universally and authentically to executives, IT professionals, finance and operations folks, and many others.

Who makes a good technology evangelist?

It doesn’t matter what your company does, the role of technology evangelist requires a unique blend of talents and traits. Once identified, these traits should absolutely be cultivated. What evangelists bring:

What does a tech evangelist actually do (and why would we need one)?

The specific role of the evangelist can vary, depending on your business and the markets / customers you serve. In my experience, the very best evangelists are often extroverts and road warriors. These folks derive energy and joy from giving presentations at industry conferences and providing direct support to customers, as well presenting dozens of webinars each year (full disclosure, this is NOT at all my own personal super-power, and it would consume a massive amount of my mental energy if I was solely responsible for this). Your evangelist might be a producer of other content — from customer-facing training and support materials, or wrap-around content relevant to your industry, to conducting related research to share with your market.

How can we best support / unleash our technology evangelist(s)?

What is important organizationally is to support the evangelist in her / his zeal for spreading your company’s message, without introducing too many constraints. This can admittedly be hard to rationalize in resource-constrained environments, but the outcomes often more than justify this investment. The role of the evangelist is to galvanize — which can absolutely have a profound and positive net impact across the business — measured in bookings, qualified leads, organic web traffic, brand strength and resilience, quashing the competition, attracting and retaining top talent, and more. Your evangelist might be asked to carry a sales quota, or have targets for establishing key partnerships. Or your evangelist might be measured on digital demand-generation metrics — on how much organic traffic to your website is produced from the evangelist’s written / audio / video content. But, be careful — trying to saddle these people with too narrow of a goal-set can stifle their creativity and sub-optimize their efforts.

As Theo Priestly pointed out in his Forbes post, “Evangelism creates a human connection with buyers and consumers to technology way beyond typical content marketing means because there’s a face and a name relaying the story, expressing the opinion, and ultimately influencing a decision.”

So where do you find a technology evangelist?

Chances are, you may have a burgeoning technology evangelist already in your midst. Many employees of small-scale companies have innate enthusiasm for your mission. If cultivated, this energy could become fully realized evangelism. You want to find someone who can be utterly convincing without it ever seeming like a “sales pitch.” You want the individual who can articulate the power of your technology, but in ways anyone could access and understand. You want the evangelist to be someone who has already “won over” a group of devoted followers — fellow staff members, customers, investors, media representatives, and others.

What one mistake should we avoid regarding technology evangelist(s)?

Be decisive, but don’t force it. Like so many things in the small-scale SaaS world, finding an evangelist seems to work best when it happens in an organic way, whereas trying to force it by quickly recruiting for the role can end badly. Often someone just kind of eases into these activities and ultimately into a more formalized role. This was the case with the outstanding technology evangelist described above, which was certainly fortuitous. Then again, when you have the right person, don’t be afraid to take the leap and make the commitment. These folks are never happier than when preaching your company’s gospel; and they can definitely accelerate your your efforts to make your mark on the world.

We’ve all been there — stuck between a rock and a hard place. In the small-scale SaaS world, there is a particular version of this universal issue. On the one hand, we need to rapidly broaden and deepen our product offering, in order to increase our product’s appeal and expand its addressable market. On the other hand, we need to generate immediate-term sales dollars, even if what the customers want / need / think-they-are-buying creates misalignment or friction against our existing solution and the product direction we’re seeking to fund with these very sales. It’s a vicious, unforgiving dynamic that can be a difficult cycle to break.

In spending time recently with a number of small-scale business operators, I’ve heard this issue come up frequently. Which reminded me of a couple simple exercises and tools that can raise awareness around this issue and help organizations avoid this tempting trap. Really, it comes down to the cost-benefit of signing on new customers in an unselective way. We tend to see and quantify the benefits of new customer acquisition very clearly: “this deal will bring in $X of recurring revenue and $Y of cash today!” What we don’t see even remotely as clearly is the organizational cost / burden of servicing that customer.

One effective exercise to combat our blindness on this issue is to fill out what we lovingly call the “Cascade of Pain.” In the Cascade of Pain, we have a diverse set of team members conjure up an existing customer that is particularly challenging to satisfy. Most every company has at least one customer in their early days where this is true: “No matter what we do, we just can’t seem to deliver to this customer what we’ve promised; they just aren’t a fit for where we are today.” In this exercise, we then we go through — department by department — and identify the range of pain that our organization has experienced as a result of our having sold this ill-fitting client (or multiple clients). Below is a sanitized version of the type of output that typically comes from this exercise:

Captured it in this way, it becomes clear that the pain from signing bad-fit customers is a burden on everyone across the entire organization. Sometimes simply codifying the pain is enough for organizations to recognize and reign-in ill-advised sales. But let’s face it, the pull of prospective revenue is powerful and the pressure to drive sales is unrelenting. In these cases, it also helps to be highly prescriptive on the front-end about deals to chase versus those to be avoided at all costs. The relatively simple exercise of establishing “Right Fit” criteria for your product can be very effective. Basically, this exercise comes at the same problem from the exact opposite perspective by asking: “What do our best customers look like / what do they have in common?” This goes far beyond the most obvious questions such as market segment (e.g. wholesalers vs. resellers vs. retailers) or size of customers (e.g. SMB vs. mid-market vs. enterprise) and gets more to the heart of how these customers interface with our company and our solution. Below are some of the questions that commonly come up:

Each category or product will have its own unique questions, but these tend to be broadly applicable. Capturing them is a critically important step, but it is really just the beginning. Incorporating them into the company DNA is an organization-wide and ongoing endeavor. It includes identifying which “Right Fit Criteria” have some latitude versus which ones are non-negotiables. It also has a major training component — certainly among sales people for use in the selling process, but also across all departments. Some systematization also helps — for instance, including some version of these questions as fields in your SFA platform. Finally, it is always a good idea to establish some processes around them. For instance, in those cases where we are knowingly going to go after a customer that falls outside our strike-zone, at least let’s make sure that we do it with sign-off from all of the necessary / effected parties, full knowledge of where the gaps are, and a plan from the get-go as to how we are going to mitigate the risks.

Because the truth is that it is our job in small-scale companies to test the boundaries of what is possible and to stretch the limits of our products and our organizations. But, that doesn’t mean we should do so blindly, or without having first clearly identified precisely where those boundaries are, and where we are comfortable pushing them.

I stated in a recent post that developing a core set of disciplines is critical to the success of B-2-B SaaS companies. The main point being that such disciplines are universally valuable in virtually any market, but also pragmatically flexible and tactically applicable across a wide range of highly specific situations.

Because, like many things, this sounds good when you say it fast, the purpose of this post is to tackle this idea a little more slowly. The aim here is to explain and explore some of these disciplines more deeply, with an emphasis on (a) why they matter, (b) what they tend to look like within companies, and (c) how they measurably impact business outcomes. In the end, I’ll also present them within a framework to make it easier to mentally organize and actively implement them.

When companies build this set of 8 capabilities featured below, they generally put themselves in a very good position to succeed.

1. GO-TO-MARKET RIGOR: A purposeful, structured approach to what / why / how / to whom we sell.

2. TOP-LINE TACTICS: Detailed execution from top-of-funnel all the way through to successful sales, renewals, & upsells / cross-sells:

3. CLIENT JOURNEY MAPPING: Seeing the world through clients’ eyes & orienting around that vision:

4. OPPORTUNITY-LED INVESTMENT: Developing what matters most to the market and which it will reward with spend:

5. TEAM ALIGNMENT: More than just the right pieces; rather also how they fit and work together.

6. CATALYZING CULTURE: Growth mindset as a way of life & commitment to organizational health.

7. THOUGHTFUL GOAL-SETTING: Holistic attentiveness to inputs and outputs that sustain the business.

8. LEADING CHANGE: Highly developed ability to manage the one universal constant — change.

It’s important to note that one critically important discipline may seem conspicuous in its absence from this list: the capability to efficiently and effectively create world-class software solutions. I want to be careful to stress that this is so central to any SaaS business that it is a sine qua non that underpins and is interwoven into all of the other disciplines. This topic — appropriately — gets tons of coverage on this blog, so it has not been given top-billing here.

Admittedly, there is a lot to the 8 disciplines above; and they can certainly be a bit overwhelming. I find that thinking about them within a broader framework is helpful. Specifically, I like to organize them in a balanced way around a company’s primary stakeholder groups (described further in this post), with each of these disciplines addressing particularly well some of the core needs of each stakeholder group. This is what it looks like:

I find this format to offer a shared language and view for assessing the health of a company, diagnosing its pressing needs, and agreeing on priority areas for investment.

This framework continues to be an evolving work in progress, so please share any comments, questions or experiences you’ve had with any similar or divergent approaches. Oh…and…I don’t have a particularly snappy title for this framework, so if you have any recommendations, I’d gratefully welcome them — thanks in advance!

I wrote in a previous post about defining a SaaS business’ product vision, and in another one about orienting company operations around the needs of key stakeholder groups. Each of those activities plays a role in ensuring alignment and optimization of a company’s limited resources. I’ve since read this post from Josh Schachter which beautifully ties together those and many related ideas. His article “How Teams Can Outperform Using the Startup Ops Pyramid” introduces an excellent model for establishing a shared mission and “unifying any multi-disciplinary team on a single set of goals.” For years, our teams at a wide range of SaaS businesses have been using (and consistently inspecting & adapting) a similar model for this exact purpose. And while there are certainly some distinctions between our two models in terms of terminology and emphasis, my hope today is simply to build upon Josh Schachter’s excellent work.

Specifically, at the top of his Startup Ops Pyramid is the team’s vision. The article cites the very useful metaphor (made famous by former Medtronic CEO Bill George) of vision as true north for a team. It also establishes the key criterion that a vision must be simultaneously “aspirational, yet still relevant to present day.” The article provides some additional nuggets about vision, before moving on to discuss “vision pillars” (which our model would classify as “strategic pillars” (potato, po-TAH-to, as they say)) and other elements of the pyramid. What I want to double-click on here, though, is this crucially important — but maddeningly elusive — task of setting a team’s vision.

The bottom line is: setting a vision is hard. And frustrating. And, if not actively leveraged, commonly not worth the time and energy that goes into creating it. In many people’s minds, it’s right up there with crafting the much-maligned “mission statement” in terms of incurring organizational brain damage or inciting collective eye-rolling. But that doesn’t need to be the case; and I’m hoping the following points can help alleviate some of the pain — because successfully identifying your company’s true north is totally worth the effort.

More than anything else, I’ve observed what makes vision-setting hard is the monolithic and high-stakes nature of it. After all, the whole purpose is to distill the vastness of everything we are as a company and everything we want to become in the future into one statement. One single, pithy, inspiring-but-credible, non-constraining-but-also-non-delusional, universally-relevant-but-narrowly-applicable, not-too-jargon-filled, baby-bear-just-right kind of a statement. In other words, it’s extremely difficult to do, and in many ways is set-up for failure. Why? Because we want our vision / mission to be too many things to too many people and for it to do way too much. We expect the vision to be everything from the words we see on the splash-page of our website, to the opening statement we use in every sales call, to the ethos we use to recruit team-members, to the guidance we consult to set detailed performance metrics, to the all-knowing arbiter for helping us prioritize what features to build in our solution, and countless other tasks for which it is likely ill-equipped.

To battle this, my argument is NOT to grind away at defining and concisely codifying that one, shining true north. Nor is it to better delineate between terms such as vision / mission / strategy (although there are absolutely useful distinctions). Rather, I want to try to expand upon this idea of true north from being one single point of light, and re-imagine it as a whole constellation of separate, but intimately connected and interdependent guide stars, that a company can truly use to light the path forward.

Specifically, if we allow ourselves to temporarily avoid wordsmithing (i.e. forget about the loaded terms “mission” or “vision” and stop worrying about how it sounds!), we can ask and answer a whole series of questions that help us think more holistically about who and what we want to become. The collective output, of these simple but profound exercises can then be referenced as needed by a range of stakeholders. It can also be flexibly leveraged to more precisely fulfill the kinds of organizational needs described above. I call these “existential questions,” and a below are seven of them that we like to use to help create our constellation of true north stars:

1. What impact do we want to have on the world?

2. In a very general sense, what do we want to be as a company when we grow up?

3. What business are we in?

4. What is our product offering today and in its ultimate expression? Why, how, to whom (and against whom) do we sell it?

5. What are we passionate about? What are we good at? What will people pay us for? Where do all three of these things overlap?

6. What does the market think about us? How do we want to be perceived? What stands in the way of getting from the current to desired perception?

7. How do we want to work? What kind of environment do we want to create?

Using Your Constellation:

As I write this, I realize that there are so many more exercises that could be included in the list above. And yet, this seems like plenty for now. Hopefully, I’ve expanded Josh Schacter’s truth north vision from single star into a broad-based constellation of north stars to by which to navigate. The constellation can be referenced in all the ways the variety of stakeholders need: how to present ourselves in an RFP, how to represent ourselves in creating a job description, and how to talk about the product roadmap in a sensible and compelling way, for example. That’s a lot to ask of one, thoughtful, single vision statement.

But, far more important than the series of exercises, is how your organization chooses to view and use the work that comes from them. I have found that the collective output and learning from these types of exercises can offer a “true north constellation” that is at once specific and clear, but also flexible, broadly applicable, and pragmatically actionable — often far more so than a vision statement in a traditional sense. In my experience, this work is equally valuable either as a complement to your company’s existing vision statement, or as an alternative to the challenging task of crafting one.

Still, as we often say, “The hard work starts AFTER the meeting;” and this is absolutely the case in connection to these “existential questions.” Accordingly, I hope to focus a future post on steps to ensure the organization is actualizing the ideals envisioned in these exercises and getting better at doing so every single day.

In dynamic, growing organizations, the relationship between the CEO and CTO is critically important. Unfortunately, this partnership often doesn’t get the attention it deserves. And, in some ways, it is a relationship that is set up with inherent tension. So, what are some things the CEO and CTO should be making time to talk about?

This was a topic I was invited to cover, from a CEO’s perspective, at a recent gathering of CTO’s. Below is a series of short videos that capture and share some of the main points from that session.

Introduction: What is your CEO thinking (and likely not telling you)? — 7 minutes

Part 1: Re-thinking Investment: Building a Dream Home — 3 minutes

Part 2: Bridging the Gap: From Vision to Story Points — 4 minutes

Part 3: Doing vs. Building: The Whole People Thing — 4 minutes

Part 4: Nurturing Purpose: Love Languages and Left Brainers — 3 minutes

Part 5: Surviving Communications: Avoiding Death by Meeting — 5 minutes