Valuations for publicly traded SaaS businesses are bananas right now. At the time of this post, Zoom’s enterprise value relative to its last twelve months of revenue (EV / LTM) was an eye-popping 58.41x. Veeva’s EV / LTM ratio was 37.02x; and “lowly” Salesforce’s was 10.03x. And it’s not just the stock market; valuations for privately owned SaaS businesses are also flying high. Against this backdrop, a colleague recently shared with me commentary from a similarly frothy time for software businesses. In mid-2011, legendary venture capitalist Bill Gurley tackled the topic of business valuations in his Above the Crowd blog with this article: “All Revenue is Not Created Equal: The Keys to the 10X Revenue Club” (5/24/11).

In this piece, Gurley makes a compelling case against the use of revenue multiples as a means for valuing businesses (“…the crudest valuation tool of them all”). But, seemingly acknowledging the ubiquity and simplicity of revenue multiples relative to his favored Discounted Cash Flow analysis, he then goes on to comprehensively explain the characteristics of high-quality revenue companies versus low-quality revenue companies. These differences, he argues, are what accounts for high valuations (10x+) for some companies, and not for many others. In some ways, the article offers a fun look-back to a seemingly quainter time (e.g. LinkedIn had just gone public that week in 2011, and analysts were skeptically scrutinizing its implied multiple of 11.8x — 15x forward revenues). But it is also a timeless study, with many insights that remain applicable today. With that in mind, below is a quick re-cap of Gurley’s Top 10 business characteristics for gaining entry into the “10x Club,” along with some added thoughts about how these apply today within Lock 8 Partners’ core focus area of small-scale SaaS businesses:

Conclusion:

Managing this 10X Scorecard can seem daunting; many of the components are interdependent. And in small-scale, resource-constrained SaaS business, the tyranny of the urgent can overwhelm even the best laid plans. While year-end brings the customary focus on the planning for the New Year, aligning those plans with your equity value aspirations is good discipline. Because, regardless of whether you’re doing $1M or $10B of revenue — and regardless of whether it is 2011 or 2021 — the characteristics of what makes a quality business remain broadly the same: sticky product, competitive moat, high gross margins, and bankable counterparties are critical for long-term success…and the market will value your business at its discretion.

Tis the season…not for jolliness…but for annual forecasting. Countless companies spend the month of December frantically closing out the current year, while scrambling to codify goals for the fiscal year ahead. So, for many small-scale SaaS businesses, this is decidedly NOT the most wonderful time of the year. Rather, when it comes to financial planning and analysis, it can be a time of feast or famine. Famine in this case is represented by simply not doing any intentional planning. A surprising number of small software companies don’t share fiscal goals with their teams, or even set formalized financial plans whatsoever. Feasting, in this case, occurs when a leader’s eyes are bigger than their mouth, resulting in an unreasonably aggressive growth plan based on exuberant hope more than rational thought. Perhaps this is less like feasting, and more like binge-eating junk-food (in that it is based on impulse, offers a temporary jolt, induces sickness soon after, and is terrible health-wise in the long-term). But neither of these extremes is necessary; and a thoughtful plan does not require gobs of bureaucratic process (one of the primary excuses offered for this feast / famine dynamic). Rather, we’ve seen that the simple concept of triangulation can efficiently produce the building blocks of an informed financial plan that balances multiple perspectives on the business. Here’s how it works:

First thing first, this approach focuses overwhelmingly on setting the top-line goals for a business. The long-pole in the financial planning tent is this top-line goal (also known variously as: revenue, bookings, ARR, and sales). This is because sales performance ultimately dictates the money flowing into the business and highly influences the expense levels the business can sustain. Note: admittedly this is more nuanced in businesses with outside funding, but eventually holds true as they mature toward cash-flow breakeven. Bookings are also the most highly variable / least-controllable aspect of any plan, as discussed in this prior post; and getting the top-line goal wrong can unleash a cascade of pain throughout the entire business. For these reasons, setting an appropriate top-line goal is the critical step in developing a sound plan. The reality is, that this goal must be ambitious enough to please financial stakeholders, realistic enough for the team to execute with confidence, and based credibly on relevant historical data (while also not being shackled to the past). A tall order, indeed.

To ultimately arrive at an appropriate goal, we like to start by pulling together three different top-line targets based on three distinct views into the business. Later we’ll compare / contrast / compromise across the three resulting targets, hence the term triangulation. The three perspectives in play are (1) top-down, (2) left-to-right, and (3) bottoms-up, as follows:

Generally speaking, Left-to-Right tends to be the middle-child in our family of goals — neither the aggressive hyper-achiever, nor the black-sheep slacker — just…meh. (Note: this last statement comes from a card-carrying middle-child).

Bottoms-Up: This approach constructs a bookings goal from the bottom up and represents the perspective of the person / people responsible for driving day-to-day sales results (e.g. CRO, VP of Sales, VP of Marketing). This perspective starts from $0 on day 1 of a fiscal year and assumes “nothing happens until someone sells something.” More mechanically, it establishes a bookings forecast from its component parts by building up a notional population of representative sales deals across a time-period. This approach tends to incorporate multiple inputs into detailed models, including:

The resulting forecast from such an approach tends to be quite conservative, sometimes prompting accusations of sandbagging by its advocates. Almost without fail, this will be the lowest among our trio of prospective top-line targets.

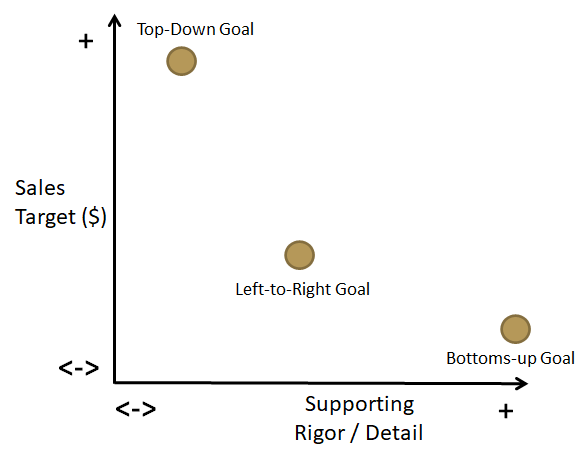

Triangulating: Simply quantifying each of these different perspectives is certainly a step toward a more inclusive and informed top-line goal. But a bit more work at this point is what yields the real progress. The truth is that the three different methodologies produce widely divergent results, both in terms of target figures and the rigor used to arrive at them, so compromise is necessary. Graphically, these could be plotted like this.

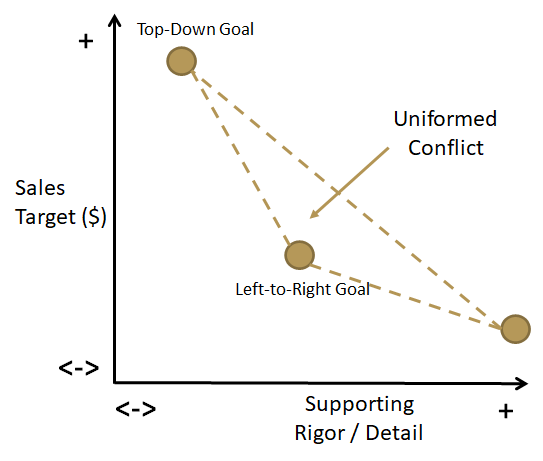

Each goal has its own shortcomings, and none of these goals tends to unilaterally offer an ideal bookings target. Without further discussion, these different data points simply shine a light on the misalignment that commonly exists across the various stakeholders. This can look like this:

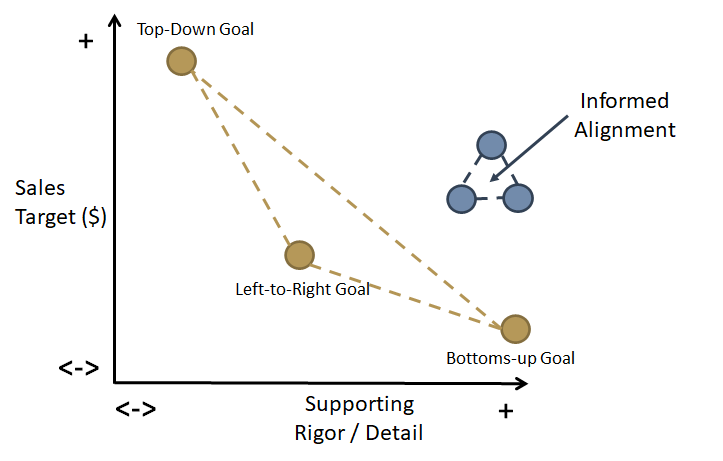

But these inputs also provide the forum for an interactive discussion around the drivers of each. Optimally, organizations can move beyond this zone of Uninformed Conflict simply by asking pointed questions of each goal:

This exercise forces people out of their default perspectives and drives productive (albeit, often uncomfortable) discussions. Inevitably, this drives more informed goal-setting and better alignment across the business…and quite frequently, it helps move the top-line goal up and to the right in our now-familiar graph:

Conclusion: The top-line goal is critical to annual planning efforts. To be fit for purpose, it must balance ambition, credibility, and executability. Only by clearing this bar will it fully serve its multifaceted purpose: to please optimistic financial stakeholders, satisfy the inherent skepticism of internal number-crunchers, and pass the “red-face test” among the troops. Admittedly, this is only a start; and many other components are needed to really nail annual planning. But getting this goal right is a great foundation around which to build; and triangulating across these multiple perspectives is a simple way to inform this process. Plus, doing so is a good way to make the New Year something really worthy of celebration by all stakeholders.

Note: This is a loosely defined “Part 2” to a prior post entitled: “Pulling Up from the Weeds of Cash Conservation.”

There is an old English adage: Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. As explained in this HBR article and per the website PhraseMix, “This phrase is usually used to give advice to someone who’s using their money, power, or skill in a way that’s not very wise.” This sentiment has particular relevance to leaders of small-scale SaaS businesses — not as a warning against an unchecked abuse of power, but rather as guidance around how they spend their most valuable commodity — time.

Taking a step backward, entrepreneurial leaders are overwhelmingly encouraged to be scrappy. Countless well-worn terms underscore the seemingly universal acceptance of this common wisdom: hands-on, roll-up the sleeves, leading from the front, wearing many hats, and servant leadership, to name just a few. The truth is that these terms are commonplace because this approach works well in growing small-scale businesses…until it doesn’t.

First, let’s look at some of the important benefits of a “can do” attitude in a hyper-engaged leader:

In these and other situations, leaders are motivated and rewarded for jumping into the fray with a versatile, “no-job-is-too-small” mindset. But these precise behaviors backfire as businesses begin to scale:

So how can leaders pull out of the weeds and find the right altitude, while keeping their feet on the ground? The truth is — like most issues of leadership — there are no easy answers. But disciplined leaders can consistently ask and answer a few questions to help make course corrections to help them fly right:

The road from “small-scale” to “growing” rarely follows a consistent, upward path; and there are few easy answers to the question of whether a leader should be above or below the “I can do that” line at any given moment. Rather, it’s useful to maintain a flexible mindset on this front. This will help leaders determine when to ascend or descend across various “altitudes” of learning, team building, financial stewardship, and many other responsibilities that fall under their purview. In a complex and constantly changing environment, it is well worth it for wise leaders to ask whether they “should” do things, even / especially when they clearly can.

It was 2001; and my boss was impressive — some would say intimidating. A whiz-kid founder and CEO of a fast-growing start-up that had raised capital at lofty valuations, he was precociously business-savvy and had a seemingly unshakable self-confidence. All of which made it that much more remarkable when he put his hands up and uttered those unforgettable words: “You convinced me.”

The truth is that we had very different leadership styles; and I often found myself filing the minority report when it came to debates among our company’s leadership team. But on this day, (and many times thereafter), I was grateful to be offered the opportunity to successfully make my case. I remember being surprised that day about the outcome itself, and about the impact it had on me — I’ll never forget that feeling of having a real voice in the business. Fast forward twenty years: I participate in many similar business debates, but now I often find myself in the senior role. I’ve learned that those same three words have enormous power, not only to make someone’s day…but to profoundly influence how businesses tackle challenges. I try to keep them top of mind and use them whenever possible. Below are some thoughts on why this practice works so well and some safety precautions when wielding this powerful tool.

At a primal level, it’s obvious why this can be such a potent approach — it is a succinct and unambiguous way for leaders to share decision-making authority with less senior folks. Beyond that, though, some subtle nuances make it consistently effective in small-scale growth companies:

Like any powerful instrument, though, using this approach comes with related dangers. Below are a few cautionary thoughts for the safe operation of this tool.

Looking back, I realize how much I learned from that boss back in the early 00’s; and no lesson was more valuable than this one. Having a legitimate forum to change our CEO’s thinking offered a feeling of empowerment that I still haven’t forgotten. And, I was a member of the senior leadership team…which further highlights just how impactful it can be when leaders create this type of environment all throughout their organizations. A big step in this direction can be taken with three simple words: “You convinced me.”

From time to time, we use this forum to share observations and trends from webinars or virtual conferences (here); and sometimes we invite guest-bloggers to offer insights from their own experiences (here and here). This post does both of those things at once. Our friend and peer, Mike Dzik, is a Growth Partner at Radian Capital (full disclosure: one of Lock 8’s investors), where he works with Radian’s portfolio companies on their respective go to market strategies spanning marketing, sales and customer success initiatives. Last week, Mike attended the TOPO Virtual Summit a three-day virtual conference for sales, sales development, and marketing practitioners; and he was generous to share with us his impressions of the event. He’s also agreed to allow us to share those observations here on Made not Found. So, with no further ado, I’ll turn it over to Mike, below:

I hope everyone is doing well and off to a fast start for Q4. I spent some time attending the TOPO Virtual Go To Market Summit this week and wanted to share 5 key themes surrounding 2021 (below).

Thanks, Mike, for these pearls. There are so many good virtual events out there; and it is impossible to free up the space to attend them all. We’re grateful to benefit from your participation in, and distillation of, the thought leadership coming out of the TOPO Virtual Summit.

-Todd

The television series Undercover Boss has been a guilty pleasure of mine for years. Now entering its eleventh season, the show features “high-level corporate execs (who) leave the comfort of their offices and secretly take low-level jobs within their companies to find out how things really work and what their employees truly think of them.” For cringe-worthy viewing, this one totally hits home for me.

But I also like the show’s more serious theme of “walking a mile in someone else’s shoes” in order to deeply understand that person’s experience. At Lock 8, we’ve adapted this concept to help provide insight into a key focus area for small-scale SaaS businesses. Whereas Undercover Boss leverages this approach to offer candid employee-level views into the internal workings of companies, we hope to shine a light on the experience a customer has when evaluating, selecting, and adopting a B2B software solution.

On the surface, this is a straightforward endeavor, involving a few simple steps:

Simple enough, right? Not really. Like so many things, this is easy to do poorly, and extremely difficult to do well. To help make it easier, this post will share a few tips relating to each of these deceptively challenging steps.

1. Pretend You Are a Prospect: At its most basic level, this is a role-playing exercise, so it’s absolutely critical to play your role well. This may be relatively easy for the undercover bosses referenced above (they get a cover legend and a disguise; and they go), but it is more complicated to get inside the mind(s) of a purchasing committee for a large and complex corporate enterprise. We’ve learned that it is definitely worth investing the time and effort to make it real: have a dossier, real personas, real business problems you’re solving for, deadlines, budget constraints, and even political motivations. Even go so far as to designate a few people to play different decision-maker roles. Balance the company profiles to reflect your current (vertical) targets, your buyer personas spectrum and the maturity of organization using your solution. Marketing absolutely should help develop these resources. Here’s a snapshot of just part of a dossier created by a portfolio company that recently executed such an initiative.

An additional point about this step: BE OPEN! Unlike the undercover bosses, for whom secrecy is paramount, this should NOT be a clandestine endeavor. The reality in software companies is that everyone somehow touches the customer experience. Likewise, our experience is that people in early-stage SaaS business are all operating in good faith, so there is no need to trick anyone or attempt to trip them up. Rather, everyone needs to know you’re undertaking such a journey; and each functional area needs to be part of the process. Now…you may need to make the case: why it’s important; why we need to get it right; who’s involved; what we’ll be doing; how we’ll share feedback. But these are all further arguments for doing this out in the open. Equally important: everyone at the company should hear later what was discovered, and to view the information as a learning opportunity, not a judgement. Nothing makes people more nervous than being excluded from understanding what’s happening behind the scenes or feeling like this is a test.

2. Go Through the Steps: Uh…what steps? Whereas most businesses have established a sales process with related stages and activities, these usually assume a company-centric approach, and overwhelmingly ignore the customer perspective. Customers’ motivations / activities / dynamics are effectively infinite, so identifying their purchasing steps can be paralyzingly complex. To simplify, we like to organize our efforts around “major stages” of the customer’s lifespan with a software solution. Although every product / system / technology is unique, there is a relatively small number of macro-phases on the customer journey; and these are generally consistent across different solutions. The purpose of the mental model and accompanying graphic below is to align perspectives, offer a shared vocabulary, and provide structure to the exercise.

On the principle that a picture is worth a thousand words, I’ll hope this graphic is self-explanatory. In summary, as we engage in countless customer “buying” and “owning” activities, and we organize them into these six phases: (1) awareness, (2) evaluation, (3) decision, (4) on-boarding, (5) use, and (6) advocacy. One note of caution: for complex solutions, this may end up being a grueling multi-month process. It’s important to know what you are signing up for in advance…and what your customers are going through to buy / use your products.

3. Record Your Experiences: A disciplined collection of notes will generate consistency of insight and evaluation. With more than one person involved the experience, it’s important to provide a consistent way to gather intel and feedback. That said, this doesn’t require over-thinking; and a simple note template suffices. We like an “Experience and Expectation” framework (“what did I expect?” and “what did I experience?”) to structure things. Then, just codify the experience in a linear way — capture in detail and in chronological order what happened and how it impacted the buying / owning processes outlined above.

4. Articulate the Ideal: It’s nearly impossible to simply dream up the ideal client experience, just like it is unheard of to nail product-market-fit on version 1.0 of a solution. Instead, it pays to inspect and adapt. Thankfully, the early steps of this exercise, and the current-state baseline they provide, offer an awesome foundation from which to iterate toward a vastly enhanced client experience. As a result, this step can be as simple as revisiting every step along the journey and answering the following question: “what would have made this much better?” In the best case, this can lead to a wholesale re-thinking of the journey; at a minimum, it will radically improve the existing steps of the experience.

5. Identify gaps; build a plan: For the activators in the crowd, this is the payoff where you can begin to implement necessary improvements. But be careful about succumbing to temptation. It is alluring to focus energy on an ad hoc basis to address the low hanging fruit that can be fixed easily. The problem is that this approach can break any number of existing processes that — although they may be sub-optimal — generally work today in the context of the current approach. So be careful about what you choose to “fix” as a one-off — it could just break other areas of your process. Although it requires more patience and offers delayed gratification, an orchestrated program overhaul will undoubtedly yield more substantive improvement of the overall client experience. Make a plan and take your time in executing it. Our experience is that the “customer experience re-engineering” project to come out of this exercise may take months or even years to implement.

As with most pressing, cross-company business issues, initiatives like creating an awesome CX Journey can take on a life of their own. Proceed with caution here; ensure that anything and everything you chose to do ties back to your overarching business needs. Such an effort must involve more than just the bosses; and there is no need to go undercover — doing so will allow companies to walk in their customers’ shoes…a journey well worth taking.

As a card-carrying introvert, I’ve always found industry conferences to be exhausting. Likewise, over recent months, Zoom Fatigue consistently crushes me by mid-day Friday. So, I figured that a pandemic-induced remote conference would be some kind of “snakes on a plane” hybrid, uniquely designed for my personal torture. But, having just concluded my first honest-to-goodness attendance of a multi-day virtual trade conference, I am pleased to report that I was totally wrong. Rather, the SaaStr Annual at Home conference this week was engaging, informative, and — I can’t believe I’m writing this — energizing. Having been freed from the relentless distractions and demands of in-person conferences (networking, generating leads, striving to optimize investment in Travel & Entertainment), I paid much closer attention to the valuable content sessions than I normally would. I also appreciated moments of respite throughout the day which offered the opportunity to sense-make across sessions. The net result was a solid set of takeaways for a fraction the time / effort (and $); and I thought I’d share an eclectic mix of conference tidbits below.

1. “ARR is a fact, churn is an opinion:” This was a gem from one of my favorite sessions led by Dave Kellogg, who offered a fast-paced “how-to” of useful SaaS metrics. The specific point here is that churn can be defined and manipulated in many ways (true!), with collateral damage to the integrity of other metrics (also true). The broader point, which he supported with compelling data — focus on what matters to value-creation in the business. Roger that. (Session: “Churn is Dead. Long live Net Dollar Retention with Dave Kellogg”).

2. Remaining Performance Obligation (RPO) Intro: As a quick-and-dirty definition, RPO can be thought of as deferred revenue plus backlog. The Motley Fool offers a deeper explanation here, in connection to Splunk. This item came from the same “Churn is dead” session, which was the first time I’ve heard RPO referenced in connection to private companies. Makes total sense, and I’m eager to think about this more in the context of usage-based business models. (Session: “Churn is dead. Long live Net Dollar Retention Rate with Dave Kellogg”).

3. Managing Complex Change: Arquay Harris of Slack led one of my favorite sessions, and not just because she threw out the term Kobayashi Maru in her talk (her content was valuable and preso style was super-engaging). She referenced Sylvia Duckworth (the introduction to whose work alone was worth the price of admission) and shared the deceptively powerful graphic below which captures elements of managing complex change.

I’ve written here about principles of leading change, but I think this graphic captures these concepts in an amazingly clear, concise, and digestible way. There is a 100% chance I’ll be re-using this visual down the line. (Session: “The Secrets of Managing in All Directions with Slack”).

4. Committee Buying: It’s not our imagination, there is much more buying-by-committee mid-pandemic among enterprises who are increasingly risk-averse, cost-conscious, and looking to consolidate their technology investments. Lots of work to be done around understanding more / new buyer personas and how to sell into a flatter organization where any single person has veto power. (Session: “Buying Patterns in the Enterprise: Who’s Really Buying & Why in a Post-Covid World with G2”)

5. Privacy Debt: Bessemer Venture Partners shared six predictions around the 2020 State of the Cloud (janky photo below):

The one that really resonated with me was: “Privacy debt will be the new tech debt.” In short, SaaS players that have not been making consistent, diligent investment in their solutions’ privacy envelope will undoubtedly face a reckoning where significant, costly catch-up on this front will be unavoidable. I suspect tech debt will continue to be a problem for many companies, so I’d maybe argue that privacy debt is yet another straw on the camel named “Tech Debt.” (Session: “State of the Cloud 2020: The COVID Beneficiaries Edition with Bessemer Venture Partners”).

6. Fun Still Matters: Ben Chestnut, founder and CEO of marketing platform giant Mailchimp, shared a great story of the moment when his development team transitioned from being mercenaries (less-productive clock-watchers) to missionaries (self-motivated true believers). It was when they started programming Easter Eggs into the solution. The point? Having fun is incredibly powerful in terms of culture, talent retention, brand, and so much more. True that — awesome interview. (Session: “Learning from the Lows: How Mailchimp Navigated Economic Uncertainty”).

7. Vertical SaaS Rules (Part 1): There were a number of sessions that focused on issues relating to vertical-specific SaaS businesses. We are big fans of vertical SaaS at Lock 8, so I enjoyed these immensely. Damola Ogundipe talked about how being a vertical SaaS solution gives Civic Eagle a leg-up in recruiting because it is easier to identify for culture and passion (and not just talent) relative to horizontal players. (Session: “Underserved Markets for SaaS Companies with Backstage Capital, Avisare, and Civic Eagle”).

8. Vertical SaaS Rules (Part 2): Songe Laron, CEO and Co-Founder of Squire made a compelling argument for why vertical SaaS solutions have an inherent advantage over their horizontal peers in terms of increasing average revenue per unit (ARPU) within their focused customer base. That same session underscored the corresponding point that market sizes for vertical SaaS players were often a whole lot bigger than they first appear…and that domain expertise in that market enables savvy operators to unlock TAM that remains hidden to the casual observer. Exactly! (Session: “Vertical SaaS 2.0: How Barbershops Are Creating a SaaS Rocketship with CRV and Squire”).

9. D&I — Early but Mighty: The topic of diversity and inclusion was understated, but never far from center-stage at this conference; and it came up in various organic ways throughout many sessions. I also attended one session where it was the explicit focus (“Which D&I Initiatives Really Work: The metrics you should be tracking with Notion Capital”). That session crystallized a shared conviction that advancing D&I in SaaS businesses is not only the right thing to do, but that it is also highly correlated with value creation…even as we are still early-on in the collection of supporting empirical evidence. In sum, I sensed that (a) this will be a major focus for SaaS businesses that acknowledge there is much to be done, (b) there is early demonstrable progress being made, (c) it doesn’t appear that anyone has all the answers, and / but we are feeling our way together.

10. “On” and “In the Business” versus “Out”: There is a well-known distinction between “working on your business” versus “working in your business.” What I have sometimes found off-putting about software conferences is the seemingly obsessive focus on “working out of your business.” By that I mean placing overwhelming emphasis on exits, liquidity, and valuation. Don’t get me wrong, those things are extremely important; but they can also suck all the oxygen out of the room. In this crazy, tragic COVID reality we are living through, I found that NOT to be the case at this event. Rather, I found that people were very much focused on “working on their businesses;” and it was really refreshing.

And…1 to Grow On (Humble Pie is Comfort Food): Similar to the point above, there can be a lot of posturing that occurs at SaaS conferences, and this tends to escalate in direct correlation with SaaS company valuations. Although SaaS multiples remain durable, the past six months have been enough to inject a bit of humility into all of us. This seemed evident in most sessions, where I perceived a genuine air of people wanting to support one another and offer humble assistance where possible. It created a comfortable environment for a conference; I certainly hope this aspect of our current environment has some staying power.

It is a good thing to be “coachable,” meaning capable of being easily taught and trained to do something better. It’s easy to understand why companies consistently seek to hire and reward coachable behavior in their teams. Based on this definition, I’d argue we all want to be coachable. Unfortunately, our egos often get in the way. This likely explains the countless books and articles that provide tips on how to become more coachable. These serve a valuable purpose; and I don’t have a beef with any of them. With one exception: their guidance seems to overwhelmingly focus on junior level professionals, and to largely ignore senior executives. At Lock 8, we strongly believe in the power of coaching to elevate the performance of executives and (correspondingly) the businesses they lead. This post shares some experiences and observations around coaching / coachability for people who need it just as much as anyone — seasoned senior leaders of small-scale businesses.

Contrary to popular belief, the need for coaching does not decrease as one’s proficiency / expertise / seniority increases. Elite performers of all types (e.g. athletes, performing artists, authors, painters, etc.) all tend to utilize more coaching, not less, as they advance in their respective fields. Want evidence: have you noticed the sideline of a big-time football game in recent years?

And yet, an anecdotal sampling of articles about coachability in the workplace shows an overwhelming focus on the most basic aspects of the topic. One recent article from a highly respected publication offered five tips for being more coachable — and all five of them focused on responding well to feedback. Although requesting / receiving feedback is an undeniably valuable skill, I’d argue it is a necessary, but insufficient condition to being coachable. For executives aspiring to become more coachable as their careers progress, simply getting better about asking for feedback won’t move the needle.

This all has been top-of-mind for me lately: I recently resumed working with an executive coach, after a six-year hiatus from doing so on a formal and consistent basis. The experience has been really positive. And it has been a reminder that there are wide variations in these coaching sessions, with some being truly groundbreaking and others not so much. Reflecting on this, I’ve realized that the variations are largely of my own making. Certain behaviors elevate the results, while others undermine my efforts to be coached. In short, the outcome depends on how “coachable” I’ve been in connection to a particular session. Below are some observations around my recent exec coaching experience, in hopes that they will help other execs who are looking to optimize their own coachability.

To finish where we started, we all want to be coachable. Like anything worthwhile, it takes hard work and some intentionality to make material improvement. Meanwhile, I’ve been enjoying working out the kinks as I’ve re-entered the world of working with an executive coach. And it really is worth the effort. As we say at Lock 8 all the time: coaching’s impact effects not only the person receiving the coaching, but also the team they lead and the organizations they drive.

A prior post explored the concept of customer effort as a critical driver of customer loyalty. That piece referenced Gartner research / articles (here, here, and here) which argued that creating an effortless customer experience — far more than raising customer satisfaction — is the key to retaining customers’ devotion. The data doesn’t lie; and I certainly buy into the concept. To a point.

On further reflection, though, I have a few reservations. These doubts are based on nuances specific to enterprise software and customers’ experience with business-to-business SaaS solutions. Gartner’s research appears to have been broad in scope; it seemingly covered customer service interactions around consumer products / services without focusing on specific industries. This post seeks to double-click into some subtleties to consider around customer effort, with emphasis on these dynamics within the B2B software environment.

1. Timing Matters: In B2B software, timing matters when it comes to customer effort. There is a fundamental distinction between the initial set-up period when the software is being implemented, versus the downstream steady-state period when the solution is being leveraged in a live environment by active end-users. For the sake of clarity, we might characterize these two phases / timeframes as “project” work (up-front) versus “process” work (downstream). Notwithstanding the rise of low-friction, freemium 2nd generation SaaS solutions, many complex business solutions still require thoughtful up-front project work. And, although the SaaS model has vastly simplified and accelerated technical aspects of software set-up, rolling out business solutions still demands organizational commitment of time and resources to do so properly (e.g. mapping processes, configuring work-flows, integrating with existing systems, and supporting user adoption). Gartner’s research in support of low customer effort appears to have excluded that start-up phase (project work) and focused primarily on downstream customer support inquiries (process work). The reality is that customers still need to invest to some degree in project work, even if their appetite for downstream process work is prohibitively low.

2. Value Matters: Building on the point above, savvy institutional software customers acknowledge some amount of up-front work is required to get great downstream value from a technical solution. And while all organizations strive to minimize that work (and time), they appreciate that effort and value are correlated. Gartner’s findings aside, customers are willing to invest in implementation efforts…so long as the downstream value they derive ultimately justifies that investment. Customer’s tolerance is a function of both variables — effort and value. Conversely, if effort and value are NOT correlated, the result will be a painful or seemingly never-ending implementation period, customer frustration, and an inevitable drop in customer loyalty. Said another way, the concept of customer “effort” is certainly relative; and customers must believe that their effort will be rewarded AND that the effort should be minimized with an easy solution to implement, administer, and use. It strikes me that all of these elements might be loosely plotted on a graph like this.

3. Timing Matters (Part Deux): There is another timing-related dynamic that encompasses both of the points above. Just as kids want to play with their holiday gifts immediately upon opening them, virtually all software buyers want to take advantage of their technology purchases as soon as possible. In other words, they want to shorten the time to value capture once they’ve contracted to use a software solution (and this is a critical metric for SaaS providers to measure). Experienced customers know that the more concentrated effort they put in, the faster they’ll get value from the solution. Conversely, a leading reason for slow or unsuccessful implementations is a lack of prioritization and effort on behalf of customers…which leads to dissatisfaction and churn. In contrast to Gartner’s research, this is case where low customer effort certainly will not translate into long-term loyalty. Note: There is also admittedly a nagging chicken-and-egg dynamic at play here; and it is worth asking whether these slow implementations would get higher priority with a more motivated customer if we vendors made them demonstrably easier to execute(?).

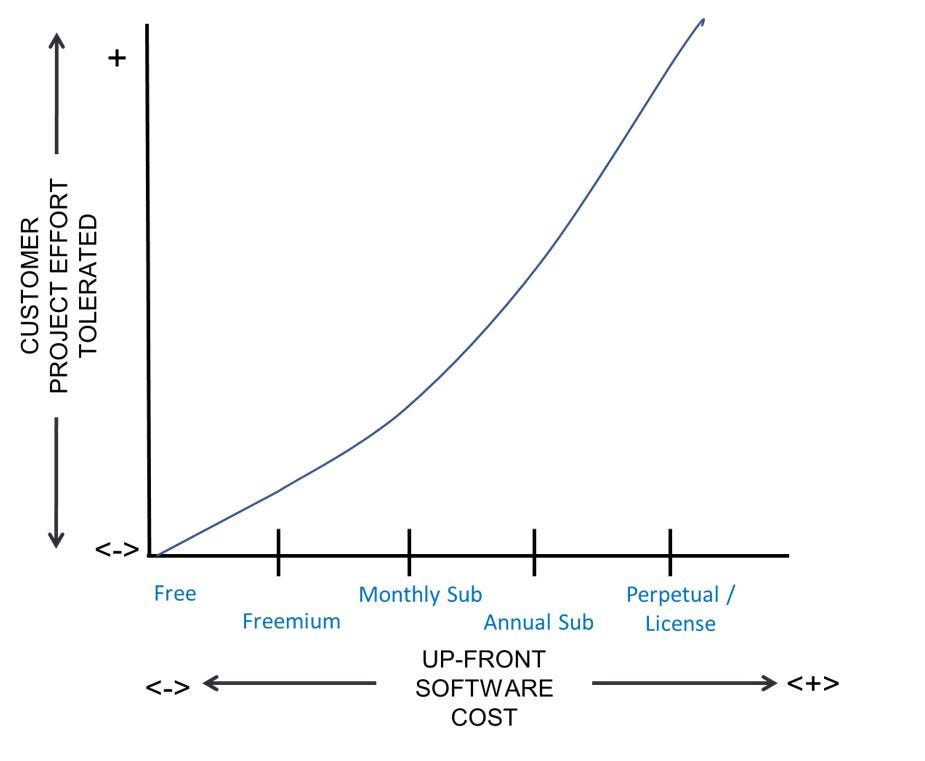

4. Economics Matter: There is an old saying that people don’t value the things they get for free. Without getting into a philosophical debate about total cost of ownership or open source software, it is safe to say that people’s commitment to any endeavor rises the more skin they have in the game. This is absolutely true when it comes to tolerance for project effort relating to software. Generally speaking, the less a business pays for software, the lower the willingness to invest effort implementing it. Free models command the lowest effort (virtually no skin in the game). Long-term license models (largely antiquated at this point) drive the highest. Many of us can remember a time when organizations paid huge sums up-front for a perpetual licenses…and then these pot-committed buyers would routinely have to spend years and fortunes implementing those same systems. Thankfully updated SaaS delivery and subscription models have put the onus on software providers to demonstrate value quickly and consistently, lest they risk churning the very customers they worked so hard to acquire. In any case, it strikes me as incomplete to say that low effort is unequivocally the highest determiner of customer loyalty. Rather, business model and up-front costs are other factors impacting customers’ tolerance for effort, with a related “effort curve” looking something like this:

In closing, the research on effortlessness brings an invaluable perspective to the rich topic of customer loyalty. But its application in the world of B2B software has its limits and should be applied with some caution. Specifically, while effortlessness may win the day in connection to downstream process work, delighting customers still seems to have a place in the world of up-front project work. Smart SaaS providers will benefit from understanding of customers’ journey with their solution and apply customer experience strategies accordingly. Similarly, it is important to understand a solution’s go-to-market strategy and packaging / pricing approach. Both will impact customers’ tolerance for investing effort, which should also inform the ideal customer experience. And, finally, the concept of “effortlessness” probably ought not be defined as NO effort. Instead, it is more relative in nature, where the work that needs to be done shouldn’t create unnecessary frustration. Said another way, effort is not the work itself; rather, it’s the infuriating customer feeling of “why does it have to be so hard?!” With that said, any and all customer work needs to be seamless and logical so they can derive value from their software purchases with as little effort as possible.

“The key to customer loyalty is an effortless customer service experience.” These seemingly innocuous words caught me flat-footed and punched me right in the nose. I’d been focused for so long on trying to delight customers that the concept of effortlessness caught me completely off-guard.

Since being captivated by the book “Ravings Fans” decades ago, I’ve been an unhesitating proponent for striving always to exceed customer expectations. But a friend and successful entrepreneur recently initiated a conversation that has brought such longstanding beliefs into question. His perspective is informed by two Gartner articles (here and here) with supporting research that challenges the actual business impact of delighting customers…and points to (low) effort as being the strongest driver to customer loyalty. These articles and concepts caught my eye and are forcing a reexamination of some of my long-held beliefs. Below are highlights from those articles along with some accompanying thoughts and considerations.

Based on research done by CEB (2013) with 97,000 customers, the data revealed four major findings:

The article goes on to offer interesting principles of low-effort service. But the truly mind-blowing part comes in a related article that encourages companies to create effortless customer service experiences (and discourages striving to create loyal customers through exceptional customer experiences). By offering statistics on the outcome of low-effort versus high-effort experiences, the following infographic makes this case in a truly compelling manner:

The takeaway from all of this, according to Gartner’s analysis, is that “customer effort is 40% more accurate at predicting customer loyalty as opposed to customer satisfaction.” Unsurprisingly, Gartner also introduces a metric, the Gartner Customer Effort Score, in order to measure the ease of customer interaction and resolution during a request for help.

To determine the score, simply calculate the percentage of customers that at least “somewhat agree” (those who give a 5 or above) that the company made it easy to resolve their issue. Seems straightforward enough in its implementation, analysis, and execution of steps to address the findings.

This all resonates with my anecdotal on-ground experience; and my takeaway from all of the above is that customer effort simply can’t be ignored. And, since the CES appears to be a metric that is easy enough to spin-up without any notable disruption to the overall client experience, there is every reason to give it a trial-run. Although I’m not quite ready to completely ditch more traditional CSAT metrics like NPS and WOMI, we certainly intend to test out CES and report-back the findings. After all, getting punched in the nose once is enough to create a desire to learn from the experience.